Our Weekly Economic News Roundup: From Scooping Ice Cream to Tasting New Coke

May 25, 2019

Why An Economist Might Like a Restaurant Queue

May 27, 2019Our story starts with a 154 pound man in a business suit. Decades ago, the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) needed guidelines for indoor climate control. To get some answers, they quantified the thermal protection from a man’s clothing (the clo scale) and a man’s activity (his MET).

At 71.6 degrees, the “ideal” room temperature they wound up with is great for most men. But not for women.

So, today we’ll first look at the impact of temperature on female productivity. And then, from women, we will move to the bigger productivity picture.

Office Temperatures

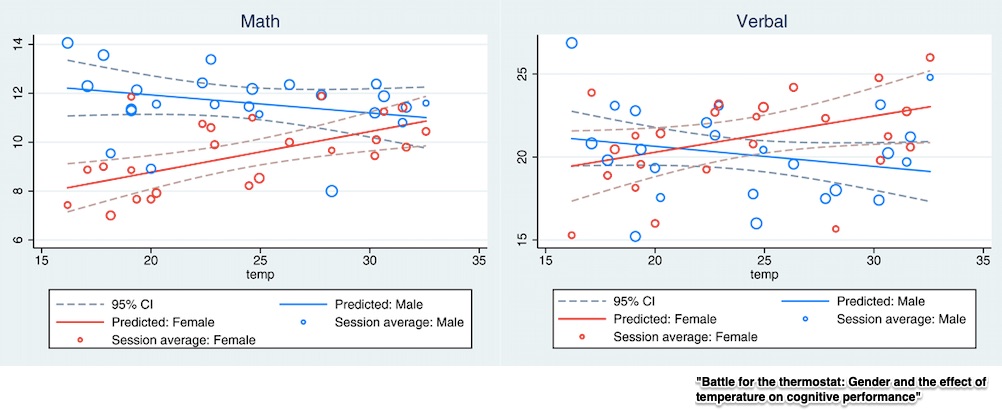

In a 2019 paper, researchers described how they varied the temperature in a lab at a university in Germany as students performed math, verbal, and cognitive tasks. During 24 sessions, with the temperature ranging from 16.29° C. (60.8° F.) to 32.57° C. (90.63° F.), they observed 543 individuals (24 or so at each session).

For the math tests, students were asked to add 50 different combinations of 2-digit numbers in 5 minutes. The verbal tests involved ten letters that could be used to form words during 5 minutes. And the cognitive problems–also with a 5 minute limit– took a bit more thought because the intuitive response was wrong. For example: “A bat and a ball cost 1.10 EUR in total. The bat costs 1.00 EUR more than the ball. How much does the ball cost?” Most of us would say the ball was $.10. The correct answer is $.05.

During the math and verbal sessions with higher temperatures, the women’s effort and accuracy increased while the men did worse. Meanwhile, the cooler temperatures flipped the outcomes. However, on the cognitive problems, the temperature created no gender disparity.

Reflecting the experiment’s results, the following graphs show that as temperature rises (x-axis) so too does female (red line) performance:

The researchers do indicate, though, that their results need further testing. Because the experiment was in a lab with college students, more varied data is necessary to confirm any universality. Anecdotal evidence though does point to their accuracy.

Our Bottom Line: Productivity

Their study also takes us to bigger questions. Whether considering women in a cold office or land, labor, and capital (factor resources) in the U.S., we are talking about how much we produce. Called productivity, you could imagine a fraction through which we compare output of goods and services to input from labor and capital. The goal? More output from less input.

The San Francisco Fed tells us that the recent increase in U.S. factor productivity is 1.42%. As you can see from their graph, it is growing. But looking back reveals why economists have been concerned:

While different office temperatures might not have affected past productivity very much, they are one of the countless labor and capital variables that affect how much we produce.

My sources and more: The up-to-date study of office temperatures is here at Plos while Nature looked at the same topic in 2015. Meanwhile, for much more U.S. data and analysis, I suggest the reports that I peeked at from the CBO and San Fransisco Fed.

Please note that our first paragraph was published in a previous econlife post.

![econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo[1]](/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo1.png#100878)