At Nautilus, one of the most popular restaurants in Nantucket, the only table you can reserve weeks in advance seats eight. Otherwise, during the summer, the queue is the rule. On the day you want to eat there, it’s best to be there, in person, for the first hour that the day’s reservations are available. After that, the phones open up. Either way–in person or by phone, there is a queue.

Nautilus:

An economist could tell you why their system works.

The Restaurant Queue

Supply and demand can explain why a restaurant could want a queue.

Supply

As much as eating establishments provide food, they are also “renting” a small piece of “land” for an hour or two. Consequently, no-shows force them to underutilize the space they sell. Through a same day reservation and walk-in policy, a popular restaurant can minimize no-shows and thereby maximize their “land” use. They also can nudge more people toward less desirable dining times.

Demand

It all works though because the restaurant is popular. With Nautilus, we are talking about just 55 seats–and eight of those could have been reserved days before. Because the restaurant is small, its limited capacity necessitates a line. Suggesting popularity, the queue sends a signal. It says that people are willing to pay with time and money to eat there. But then, the line itself becomes an incentive that increases demand. Called anticipatory consumption, it can even make the food taste better.

Analyses of the restaurant business point out that the queue’s rules need to be fair to avoid alienating diners. And they will lose people like the elderly, the disabled, and some families with young children who cannot stand in line. Also, diners who want to avoid the risk of not getting a table that evening will have planned ahead with a reservation elsewhere.

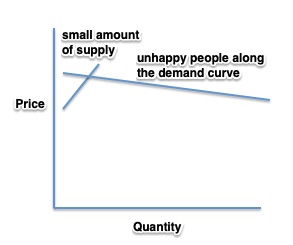

However, a supply and demand graph shows why it all works for establishments like Nautilus.

Our Bottom Line Supply and Demand

As always, we have upward sloping supply and downward sloping demand. But I’ve drawn a very short supply curve to reflect the small number of seats in the restaurant. You can see though that the demand extends over most of the quantity axis. Diners are willing and able to purchase many more meals at the restaurant than it can sell them:

The result could be a queue.

Lastly, I thought you would enjoy (as did I) returning to a Seinfeld episode on the massive line for the Soup Nazi (which I have endured–the soup was really spectacular). Do watch to the end where George returns to the line:

My sources and more: If you are going to Nantucket, you might want to read the Nantucket Today description of Nautilus. Meanwhile, this paper has the academic side and The Washington Post, the lighter side of restaurant economics. Finally, to feel better about lines, this study of anticipatory consumption is a possibility.