Banking on Marijuana

April 11, 2019

Our Weekly Economic News Roundup: From More Yogurt to Fewer Avocados

April 13, 2019We could say that the wholesome trend in food was led by yogurt. FAGE was the first Greek yogurt sold in the U.S. Then there was Chobani, Danone, and General Mills.

Less than a minute, this 2011 ad for Fage is wonderful:

Now startups have added to the yogurt lineup. Made from plants, their options give us a whole new chapter of choices. We can select Tempt Original Hemp Yogurt or Forager Creamy Dairy-free Cashewgurt. There is almond yogurt and soy yogurt. And during January, Chobani launched nine coconut-based yogurts.

According to WSJ, there are a whopping 306 yogurt varieties at a typical supermarket. But here we have a paradox. There is so much more to buy.

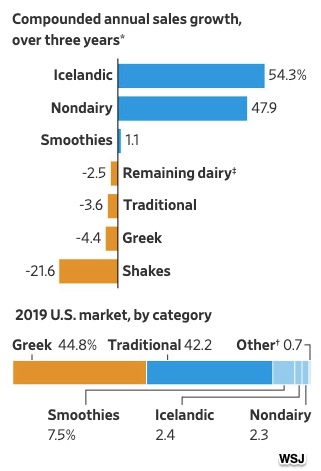

Yet people are purchasing less:

Sales are up for the newer market entries like Icelandic, a thicker kind of yogurt known as skyr (pronounced skeer). However, they remain a tiny slice of the entire market:

Where are we going? To how assortment size affects what we buy.

The Riddle of Choice Fatigue

For a long time (as reported in a past econlife) marketing scholars, behavioral economists, and psychologists have concluded that too many decisions can impact our subsequent behavior. Called choice fatigue, we get tired out from too many options. Consequently, we buy less or select an easier alternative.

But now, researchers point out that it isn’t that simple.

In fact, we have a “decision-making timeline” that can determine whether we experience choice overload. When we start to make a purchase, elaborate assortments entice many of us. However, once we actually have to choose among them, we might back off and buy nothing.

In one experiment with jelly beans and another with chocolate, Stanford researchers observed more buying with the first option than with the second one:

- First decide whether or not to buy something. Then choose from a big assortment.

- First choose from a big assortment. Then decide whether or not to buy something.

The results indicated that people want to make a purchase when they see they have many choices. However, they are less likely to buy the item if initially they have to choose from many possibilities. At first the benefits loom larger (#1). But then, the cost of choosing could be daunting (#2).

Our Bottom Line: Demand

Choice fatigue provides some insight about the demand side of markets. Too many decisions can be exhausting. Increasing cost (defined economically as sacrifice), they can make us buy less.

However, choice can also be appealing when it requires no effort.

So, returning to where we began, the yogurt section of the supermarket can indeed attract us. Then though, we see how many decisions we have to make.

Like buying a car, we wish we had a default deal rather than debating each option.

My sources and more: This WSJ article reminded me that we haven’t looked at choice fatigue in awhile. Slate summarizes some of the past research that got a second look in this Stanford paper. And thanks to Fortune for more yogurt facts, Mental Floss for Fage info, and foodrepublic for differentiating between Greek yogurt and skyr.

Our featured image is from foodrepublic.com. Our choice fatigue discussion was previously published in a past econlife.

![econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo[1]](/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo1.png#100878)