Our Weekly Economic News Roundup: From Sinking Stocks to Superstar Singers

December 22, 2018

Is Santa Earning More?

December 24, 2018In 2015, 63% of us agreed that fast shipping took three to four days:

No more…

The 2018 Consumer

Rather quickly, our perception of FAST has changed. Now it is closing in on two days.

This year, only 25% of the people in a Deloitte survey said three to four days were fast. Instead, 62% said fast delivery was two days or less. That percent climbed from last year’s 54%.

However, the vast majority of people preferred free over fast. Many of those who said free were willing to wait three to seven days for the delivery:

Nineteenth Century Fast Delivery

I couldn’t resist a bit of history.

At first, coast-to-coast 19th century mail traveled via steamship and across the Isthmus of Panama. When Henry Wells (the Wells half of Wells, Fargo) made the trip in 1852, 15 of his traveling companions died before reaching their destination and many became ill. The turning point was 1858 when Congress approved an overland route of “stages, drivers, mules and horses.” They reputedly covered 2700 miles in 24 days and nights.

By 1861, 10 days became the 19th century idea of coast-to-coast fast delivery. However, only a select few could afford it. To send a half-ounce letter, the Pony Express $1 rate was the equivalent of $31.90 today:

For packages (parcels), the alternative was Wells Fargo. No not yet an investment bank, Wells, Fargo & Co. was created by Henry Wells and William Fargo in 1852. Once the first transcontinental railroad was completed in 1869, they could move mail and packages across the country in as little as one week.

For a bit of nostalgia, you might want to look at the Wells, Fargo song from “The Music Man”:

Our Bottom Line: Reference Points

Looking at what we call fast delivery, behavioral economists would say that our reference points have shifted.

To see what they mean, I always like a gas price example. When the price per gallon is dropping from $3.00 to $2.75, we think gas is cheap. However, when the price rises from $2.50 to $2.75, the same amount can feel expensive. The reason? The context or frame for our decision has changed. It has a different reference point.

So too with delivery.

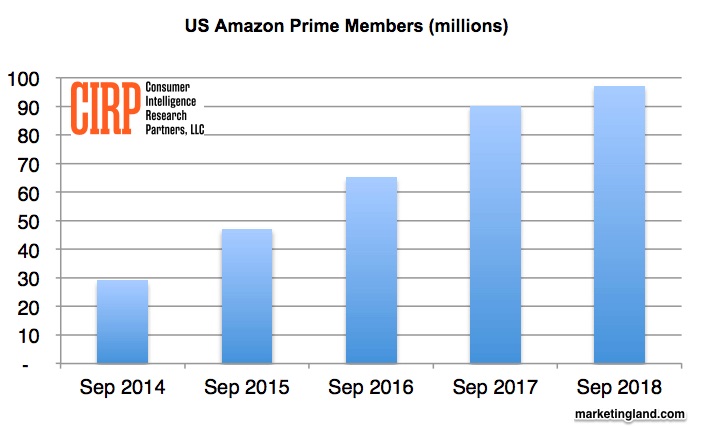

And that takes us to Amazon. As Amazon Prime members, over 100 million (12/18) of us expect “free” (after paying our yearly fee) two-day delivery:

You can see where our fast delivery reference point comes from.

My sources and more: Do look at Atlas Obscura for the interesting side of package delivery history and “A Brief History of the Package Delivery Industry” (USPS, no link existed) for the drier picture. Meanwhile, Deloitte’s annual consumer shopping survey had the contemporary fast delivery data. Then, if you want to read more about reference points, anchoring, and behavioral economics, I recommend Nobel Laureate Daniel Kahneman’s excellent Thinking Fast and Slow.

![econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo[1]](/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo1.png#100878)