The Surprising Significance of Ping Pong

January 14, 2018

Why the U.K. Wants a Latte Levy

January 16, 2018A posh London eatery just decided to charge you less on Mondays.

Bob Bob Ricard’s lobster macaroni and cheese has an off-peak price of £20.50 that rises to £26.50 on Saturday evenings. As they explained, they have a wait list of 400 for their busy days but serve only 40 lunches on certain weekdays. So why not attract those people who want to pay less?

Restaurants actually began using dynamic pricing seven years ago when Chicago’s Alinea first tried it. Charging more for that Saturday night 7:30 slot than Tuesday at 9:30, they were able to optimize their customer flow. During one Super Bowl, they tweeted, “Don’t care about football tonight? Come eat at Alinea instead. $165 super bowl special.” That 35 percent discount meant $23,800 of extra revenue or as they explained, “Not a normal night, but not a disaster.”

Somewhat similarly, apps like TasteBud enable restaurants to vary their discounts. It all depends on the day, time, demand and even the user’s buying history. Once a potential diner places an order, she will see where price is at that moment. One journalist who used the app throughout the day would have paid the least at 8:45 in the morning and during the mid-afternoon lull.

The Price Tag

Looking back, we would see it was not unusual to charge different prices for the same items…until we had price tags.

Before the 1870s, a different price for each customer had been the norm. Walking into a small London store during the early 19th century, you were prepared to bargain. Trained to haggle, clerks knew what was high, what was low and what would generate a profit. The process was time consuming and it meant the seller and buyer became adversaries.

But then we had the invention of the 19th century department store. Think New York’s Macy’s. It would have been impossible and impractical to train hundreds of employees to negotiate a price for thousands of items. The result? The price tag.

Returning to Dynamic Pricing

Now though we are almost back to where we started. While we have not returned to haggling, we do have different prices for the same item from the same seller. Whether dealing with restaurants or airlines, Disney or Amazon, we could be paying more or less than our neighbor for the same items.

Our Bottom Line: Pricing Power

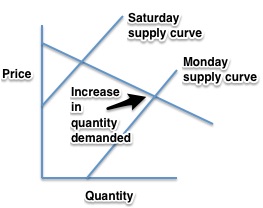

Whenever they have some monopoly power, business firms act more as price makers than price takers. Price makers have the power to shift their own supply curve to a new position. As a result, they help to decide where supply will cross demand to determine price.

Really though, it is just about the law of demand. When price drops, we are willing and able to buy more. So, by charging different prices for the same meal, Bob Bob Ricard can cater to different diners and sell more lobster mac and cheese.

My sources and more: Seeing here and here that a top London restaurant (with a Champagne button at every table) was using dynamic pricing, I thought of this app and the models they were copying at Amazon and the airlines.

Please note that sections of our dynamic pricing discussion were published in a previous econlife post.

![econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo[1]](/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo1.png#100878)