Where Grid Stress Creates Corporate Stress

December 16, 2025

Just Ask Jenna Looks At Dining Out

December 18, 2025With dynamic pricing, airlines (and other businesses) charge a menu of fares, usually depending on the day and time.

Now though, it might be replaced by surveillance pricing.

Dynamic Pricing

Our story starts several years after the 1978 Airline Deregulation Act. Because of deregulation, airline decision makers had a new world of fare making to navigate. Whereas previously government’s Civil Aeronautics Board let airlines preserve a healthy bottom line, now competition and markets set prices. Quickly moving to a dynamic pricing model and a different price for each flier, the airlines had to determine whether the flier was discretionary or business, if the flight was departing in days or months, and how many seats remained.

As you know, they never even needed to ask us. Knowing businesspeople are willing and able to pay more, they just sold the cheapest tickets to people that could remain for Saturday night or booked way in advance.

Variable Pricing

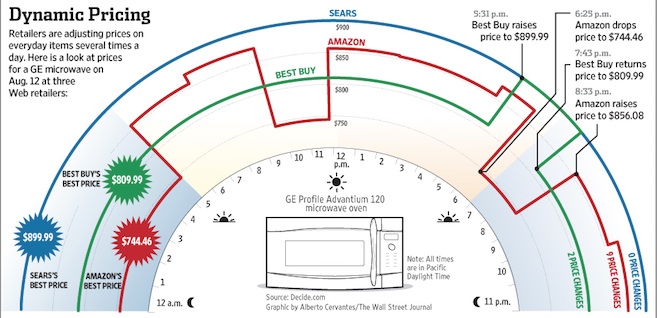

Meanwhile, Amazon had the next spin on dynamic pricing. Minute by minute, they can change a price. Then, based on a slew of facts like the number of competitors, the time, the volume of transactions, their algorithmic pricing optimizes revenue.

In the following graphic, the price of a GE microwave oven changed multiple times from 12 am to 12 pm on August 12, 2012. Although the graphic is close to 14 years old, recent Congressional testimony indicates its message remains accurate:

From: WSJ

Surveillance Pricing

Now, Consumer Reports documents that Instacart prices can vary by as much as 23% for the same item. In their study, the same basket of groceries, ranged in price from $123.15 to $114.34. While not saying that Instacart was engaging in surveillance pricing through its supermarket partners, they did imply its existence. With surveillance pricing, the retailer uses personal data including income and shopping history to price a person’s purchase.

In the Consumer Reports study, 437 volunteers, divided into four groups, purchased identical baskets of 18 to 20 goods at the same markets. Analyzing the data, they found as many as five different prices that varied from $2.56 to 7 cents for the same item.

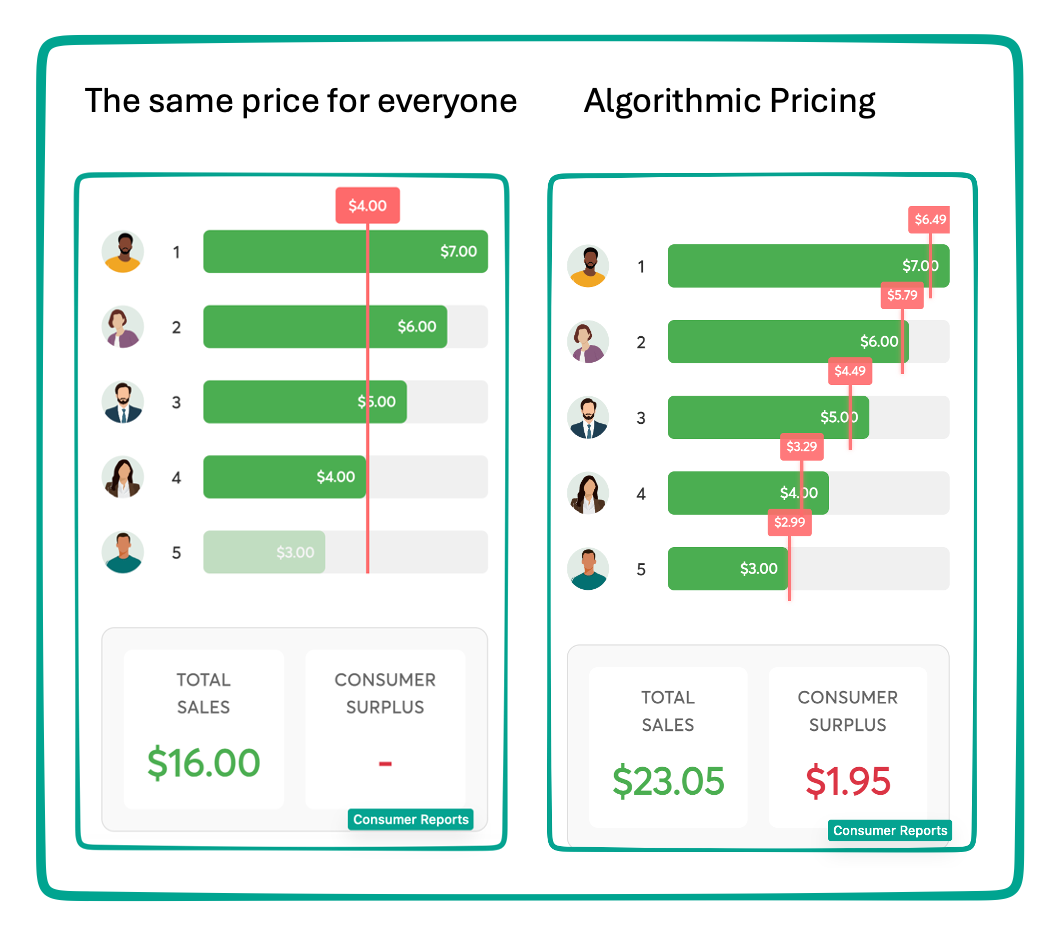

Consumer Reports showed us the difference between using and not using the algorithm. If the store knows who is willing and able to spend $7, $6, or $5 on a bag of chips, they can charge different amounts and ring up sales of $23.05 rather than $16.00 when everyone pays $4:

Our Bottom Line: Elasticity

Consumer Reports concluded that Instacart was trying to identify a customer’s “price sensitivity.” As economists, we can say they were gauging our elasticity. Defined as the relationship between a change in price and the change in quantity demanded, elasticity comes in two basic buckets. Our response to price can be inelastic or elastic (or unitary elastic but we need not consider that). Inelasticity indicates we have a minimal response to a price change for items that include necessities like milk or medication. By contrast, with luxuries, a price change can get a definitive response from us. I suspect that Instacart is trying to identify our inelastic price range by determining how much to increase a price.

My sources and more: After returning to this econlife post for the history of dynamic pricing, we moved onward to the Consumer Reports article on Instacart. Meanwhile, Congress has been looking at dynamic and surveillance pricing, here and here.

![econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo[1]](/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo1.png#100878)