One of my favorites, most of this post is a repeat from last year.

University of Minnesota Professor Joel Waldfogel explains (with a bit of a smile) that gift giving creates an “orgy of value destruction” and the “misallocation of resources.” Think of the $35 scarf you could have just received from a Cousin Camille. Because you hated it, the value of the gift shrunk to $15. Consequently, the economy lost $20 from unsuccessful gift giving.

During every Christmas holiday, we’ve referred to what economists call deadweight loss–the cost to all of us from gifts that are worth less than their price. But last year, I discovered a new way to look at it.

Preference Falsification

Sometimes we misrepresent what we really believe because we think we have to. The reason could be politics or we just might not want to hurt someone’s feelings. Duke Professor Timur Kuran said that these misrepresentations reflect our “preference falsification.” As he explains, a private truth can become a public lie.

Politics

In the political realm, he cites North Korea as an example. No one dares express dissent knowing their leader had his uncle executed. Similarly, East European dissidents had to obscure their opposition to Communist regimes while privately feeling very differently.

Public Opinion

Even in societies where we can speak freely, public opinion can muzzle us. During a podcast interview, one resident of a Florida senior citizens community said his property was vandalized when he expressed his political loyalties. Consequently, many people kept quiet. At a dinner party, many of us might hide our support of the unpopular side of a public issue.

Gift Giving

This takes me to gift giving. When we get that ugly scarf from Cousin Camille, we don’t tell her. Instead, we probably engage in preference falsification. We tell her we love it. And then next year, the same problem resurfaces.

Our Bottom Line: Market Failure

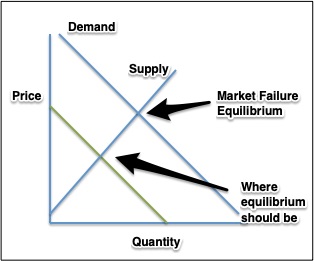

An economist might call the scarf situation a market failure. Ideally, markets are supposed to create an equilibrium price and quality that optimally satisfies buyers and sellers. However, when a scarf is really worth $15 but sold for $35, the market has failed. Because the gift giving created less utility (usefulness) the demand curve should have had a lower location:

So, where does this leave us? I’ve become ever more aware of the prevalence of preference falsification. You?

In these five minutes from Seinfeld, you can see what happens when you try to avoid market failure:

My sources and more: Through a Hidden Brain podcast, I heard Professor Timur Kuran explain preference falsification. Then, after taking a preview peek at his book, I also recommend the podcast. It made my morning four mile walk seem much briefer. Meanwhile, we’ve looked at Joel Waldfogel and the deadweight loss of gift giving, here.