In the United States, women’s economic empowerment becomes very real when we look at Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg (1933-2020). When RBG graduated from law school in 1959 as #1 in her class, NYC law firms refused to hire her. Gender was the reason.

Now, 62 years later, in the U.S. and many of the world’s other 189 economies, women have more opportunity. But not everywhere.

Women’s Economic Empowerment

Through Women, Business and the Law 2021, the World Bank Group quantifies women’s economic opportunities in 190 economies. Connecting the law and eight benchmark criteria, they look at the impact of the legal environment on the workplace and the life cycle. More precisely, their questions range from heads of households and parenting leaves to ownership rights. They inquire about domestic violence and access to credit. Then, after judging each answer on a 1-100 scale, they give countries a score.

These are the eight criteria:

The report confirms that politics matter. In the following graph, where we have more women in government, the WBL score is higher. With a y-axis indicating women in parliament, and x, the WBL score, the yellow OECD dots dominate the right while the green dots on the left represent the Middle East and North Africa. The report suggests that higher scores correlate to more female legislators:

We also see a connection between economic development and legal gender equality with high income economies both causing and benefiting from economically empowered women.

Below, you can see that the lowest score is 26.3 while the highest is 100. (I did wonder how 10 countries could possibly get 100s.) No country in the Middle East, North Africa, or South Asia had higher than a 90. In the sub-Saharan Africa group, Mauritius and South Africa had the highest scores while Sudan and Guinea Bissau were at the bottom:

The yellow and green bars display the starkest contrast between regions. So too do the pension and pay averages. At 67.5 and 73, they are lower than the other benchmarks:

Our Bottom Line: Production Possibilities Graphs

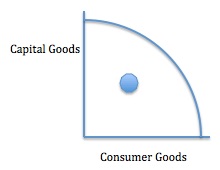

As economists, we can take the next step with a production possibilities frontier. Whereas our curved line, below, shows an economy’s maximum production potential, the dot indicates underutilization. For the economies with less than 100 scores, the dot is far from the frontier because female economic empowerment is below where it could be:

A bit of history also shows underutilization:

Comparing where we began with Ruth Bader Ginsburg in 1959 and now, we can say that our production possibilities dot moved rightward and our graph trended up. But there is much more to do.

My sources and more: Since we’ve looked at WEF Gender Gap Reports, the economic emphasis of the World Bank’s Women, Business, and the Law 2021 was the logical next step. From there, RBG was one example.

Finally, I should note that Afghanistan’s scores were among the lowest. On a 1-100 scale, for pay they got a zero: