When We Don’t Need Traffic Lights

June 30, 2021

What We Can Learn From a Tree

July 2, 2021Usually, the Texas A&M Urban Mobility Report tells us our average one-way daily commuting time.

Last year, though, it was a bit more complicated.

Commuting Time

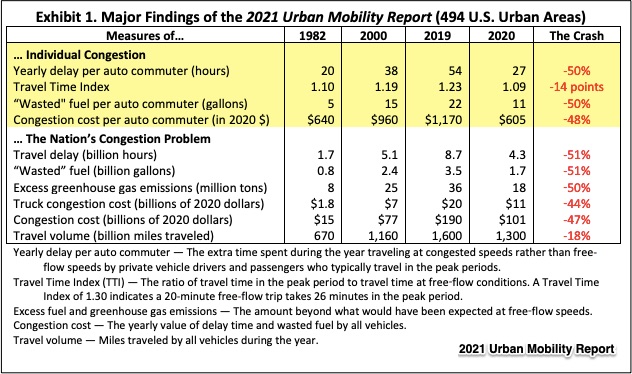

From 1982 through 2019, the congestion trend was straight upward. We had longer delays, wasted more fuel, and the dollar cost rose from $640 to $1170:

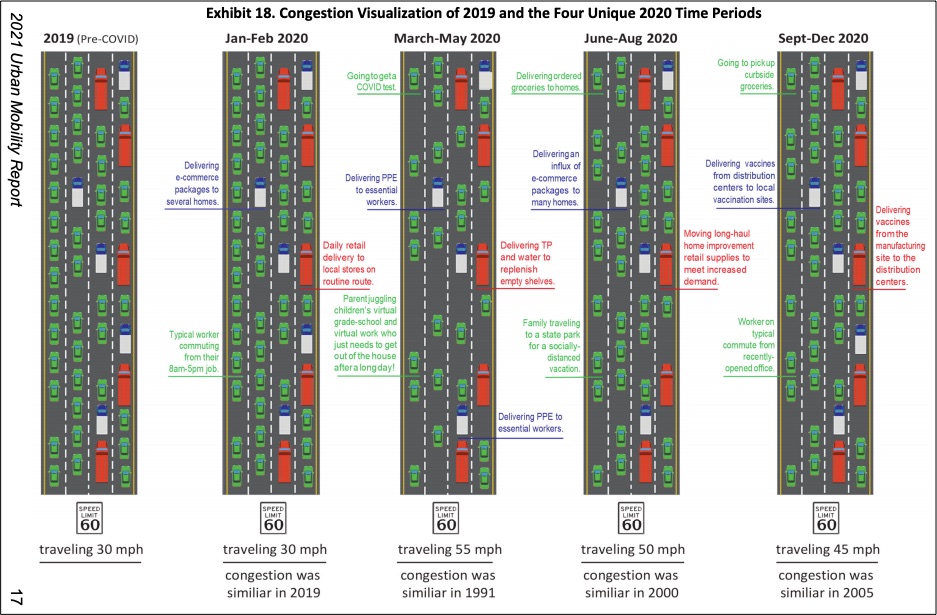

Unlike past years, the character of 2020 traffic changed four times. January and February resembled 2019. But then, as you would expect, the lockdowns from March to May pretty much emptied the roads. Congestion was down by as much as 75 percent as cars sped along at 55 MPH instead of the previous year’s 30 MPH. Illustrated below, by July and August, building to an almost normal September and October, the decline reversed:

The numbers also depended on where and when you looked.

Population

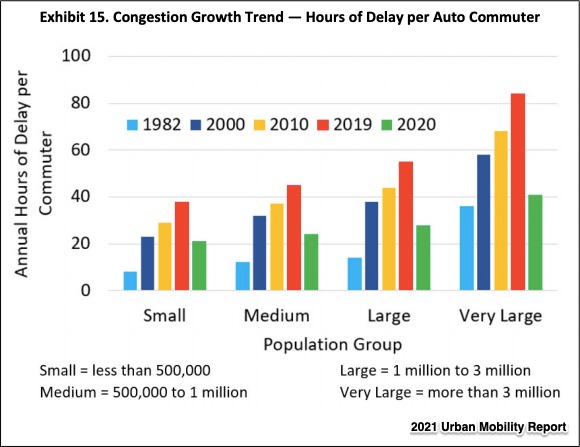

Below, we can see how average delays differed between large and small urban areas for five years:

Type of Road and Time of Day

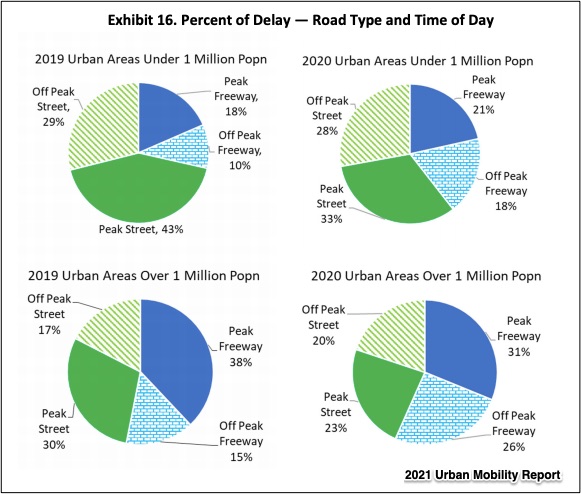

After rush hour disappeared, traffic patterns flattened during the day. We tended to drive at all hours, creating more off-peak freeway traffic:

Large Urban Regions

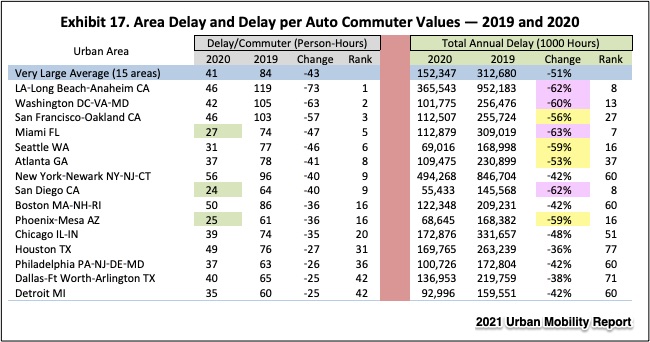

Ranked by very large urban areas, the Long Beach-Anaheim commuting areas was first, even with a substantial decline. At the same time, New York was in ninth place:

Trucks

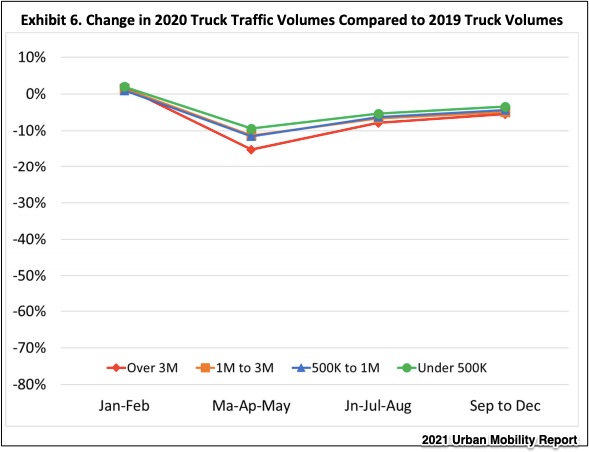

With more off peak driving, we had less of a dip in truck traffic. One big reason was home deliveries:

Our Bottom Line: Negative Externalities

Moving 5 MPH in rush hour traffic, do you ever think that you are the problem?

Four of the five major causes of congestion impose the consequences of individual decisions on unrelated third parties.

Congestion causes:

- too many car trips

- rush hour roadwork

- crashes

- stalls

- weather

Defined as the impact of an activity on an uninvolved bystander, the negative externalities of traffic congestion are gargantuan. Creating delays that are inconvenient and aggravating, they cost businesses time and money. Furthermore, when congestion relates to long commutes, according to The Washington Post, people are more likely to be obese, divorced, depressed, and have hypertension.

Since everyone of those problems ripples beyond the individual to a family, a community and even the entire country, we have a slew of negative externalities. More simply stated though, we can say the cost–defined as sacrifice–is considerable.

The question now is if we will preserve any of Covid’s positive impact on traffic jams.

My sources and more: Thanks to Bloomberg radio for alerting me to the new Texas A&M Urban Mobility Report. Please note that a part of “Our Bottom Line” was in a previous econlife post.

![econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo[1]](/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo1.png#100878)