A beer-producing abbey in Belgium has a problem. They are running out of monks.

This is the story.

Trappist Beer

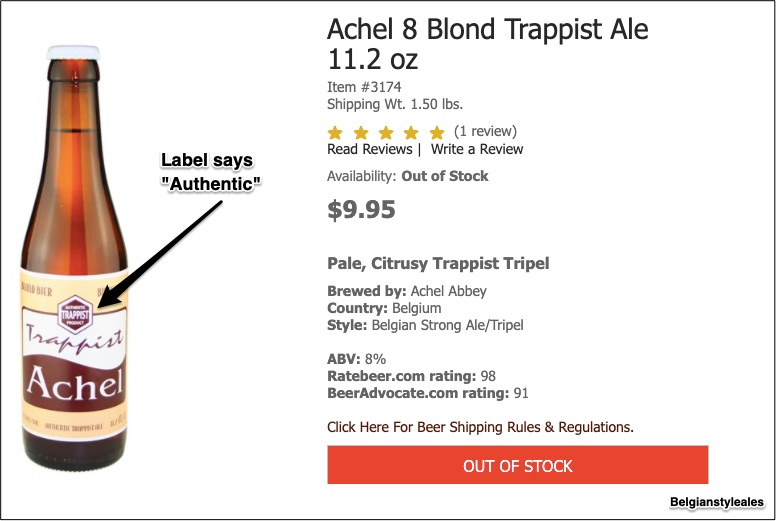

The Belgian beer produced by Trappist monks has a special designation. Fruity and high in alcohol, it can have “Authentic” on its label if monks supervise its production, if it is brewed in a monastery, and if the monastery or a charity receives all profit. The designation rules were established two decades ago when the abbeys formed the International Trappist Association. Its purpose was to protect them from commercial knockoffs that sought their cachet and premium pricing.

You can see that they need the monks to get the designation. But, because St. Benedict’s Abbey in Hamont-Achel, Belgium no longer has a monk to supervise production, it had to sacrifice the special label. Elsewhere too, monks are aging and not being replaced. They have been a part of a 200 year tradition where observant Catholic men who pray seven times a day, work with their hands as farmers, cheesemakers, brewers.

Below, the “Authentic” label that Achel Abbey will have to eliminate is on its bottle at the website that sells Belgian Style Ales. (I added the note and the arrow.):

Our Bottom Line: Human Capital

An economist would say we have been talking about human capital. Human capital takes us to one of the three factors of production from which we make all goods and services. We have the land as the place from which we work. There is the labor that is the human input. And then we have physical and human capital. Made by people, capital helps production grow. In a factory, when we add to our physical capital–to our buildings and equipment and inventory–we can produce extra goods and services. Similarly, we have a store of human capital that accumulates through education and informal knowhow. More human capital particularly can boost production.

Since the early 19th century, Trappist monks have accumulated the human capital that composed a unique brewing population. In 2007, WSJ described two monks preparing their 170-year-old recipe. It all began after morning prayer, when they mixed hot water with malt. Then, at noon, they added the hops and sugar. Next, for up to a week, enough for 21,000 bottles was boiled and then fermented. And finally, before bottling, the beer rested in tanks for as long as three months.

Having generated $77 million in revenue during 2019, the brothers that made Scourmont Abbey’s Chimay brand moved onward to vast economies of scale. Now though, there are fewer monks to preserve and build their human capital.

My sources and more: A recent WSJ article alerted me to Trappist beer and then sent me back to 2007 where they described the beer and how they produce it.