Our Weekly Economic News Roundup: From Taco Bell Tortillas to Healthcare Prices

July 6, 2019

When Cars Have To Decide Whether to Kill Grandma

July 8, 2019Yesterday morning, through a NY Times podcast, I met Brian Milo. Now 36 years old, he started at the General Motors Lordstown, Ohio factory a decade ago. As he described it, he did the venting, airbags, the radios–anything you needed inside a Chevy Cruze. The income was good. He had a middle class life with a wife, a young daughter, a house in the country, and enough extra to take some vacations. He expected to be there for the rest of his life.

But then, Chevy Cruze sales collapsed, workers were laid off, and factories closed. After 53 years, during March 2019, the GM Lordstown plant made its last car. At the same time, Brian got a letter from his employer. To continue working, he could move to the GM plant in Missouri within 10 days. Otherwise, his medical benefits, his vision, his dental, his job were all gone.

Brian told the NY Times that his wife had a healthcare job, his daughter had school, he had his house. He could not start a new job 700 miles from home within 10 days. So, he said no.

Brian Milo’s story reflects a reality faced by millions of factory workers. Whether it was less demand, offshoring, or competition from imports, people were losing the jobs they expected to have for a lifetime.

The U.S. does have a solution in place. However we are not sure if it works.

The Trade Adjustment Assistance Program (TAA)

In 1962, as trade barriers began to dissolve, an “adjustment” worker program was established. The word adjustment was crucial because the goal was moving to new jobs. To make it happen, the TAA provided the states with funding to retrain workers whose jobs were erased by trade.

Currently, the program gives participants three extra years of unemployment insurance, up to $10,000 for two years of training, and a small relocation stipend. It is supposed to facilitate change. Laid off workers will get the skills they need to function in a changing economy.

The Impact

In a recent paper, one economist tried to figure out if the TAA program was successful. If it was, then the same concept could extend to technological unemployment and beyond. His conclusions were mixed. It all depended on when and at whom you looked.

All went well during the first ten years after a layoff. Workers made a total of $50,000 more than co-workers who had not signed up or not qualified. However, after that first decade, there was a convergence. All incomes became similar.

The author of the study concluded that program’s participants were learning skills that helped them only in the short term. However, he also saw that unemployed commercial aircraft workers trained for refrigeration jobs, tractor operators, and as medical assistants. Laid off clothing workers became sewing machine operators. More generally, people wanted to become computer operators, office clerks, medical assistants.

Most crucially, the barriers that constrained moving on were tougher than many had projected or understood. Involving information, the new jobs were sometimes a mismatch. Like Brian, financial roots could prevent someone from entering an “adjustment” program. And then we also had the behavioral side where workers misjudged their current plight and thought the same jobs would return.

Our Bottom Line: Structural Unemployment

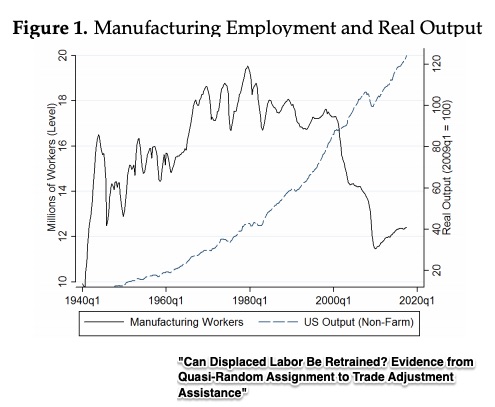

Between 2000 and 2016, the number of U.S. manufacturing jobs dropped by 6 million while manufacturing revenue was up:

An economist would say that we had structural unemployment.

One of four causes of unemployment, structural change takes us to a fundamental shift in how goods and services are produced. It relates to new kinds of capital and different skills from labor. Next, we can cite the business cycle as a source of joblessness. When there is a recession, the GDP drops and people lose their jobs. Our third kind of unemployment is seasonal. Just think of how holidays and vacations affect supply and demand. And finally, we have those everyday unavoidable reasons that create unemployment like an unhappy workplace that someone leaves.

So, where are we? We can ask if programs like the TAA will help workers like Brian Milo “adjust” to the structural change created by trade and technology.

My sources and more: Thanks to Trade Talks for introducing me to economist Ben Hyman. His podcast interview and paper on worker adjustment to trade were wonderfully enlightening. But The Daily podcast completed the picture with its focus on one man.

![econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo[1]](/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo1.png#100878)