Our Weekly Economic News Roundup: From Facebook to Teen Vogue

November 24, 2018Why a Tariff Changed Your Hiking Boots

November 26, 2018After the Ikea store in Valbo, Sweden stopped accepting cash on October 1, many of the store’s customers were happy. But not the local elderly population.

So yes, going cashless could be a bit complicated.

This is the story.

Ikea’s Experiment

It made sense for Ikea to try out a cashless store in a country where payments have become substantially digital. They recognized that they could eliminate the cost of managing cash, minimize robberies, and speed transactions. It all meant that employees could devote more time and energy to customers.

The main problem though was in the cafeteria. As a local dining spot, it attracted an elderly population that was used to cash. When some showed up with no way to pay digitally, the store even gave them free food.

Sweden’s Cashless Facts

Every other year, Sweden’s central bank (Riksbank) interviews 2,000 random individuals (aged 16-84) to learn about their payment habits. For the Riksbank’s May, 2018 report, they also did 500 interviews in rural areas to see if geography made a difference. (It did.)

The Results

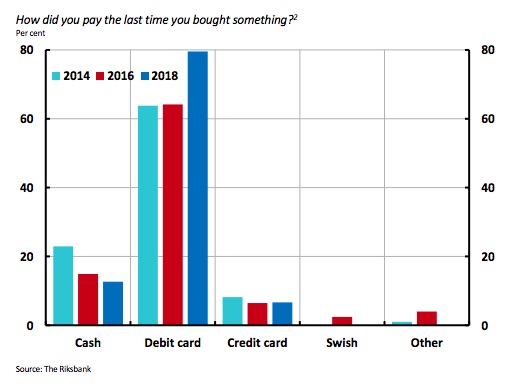

Among the survey’s participants, debit cards were by far the most popular form of payment:

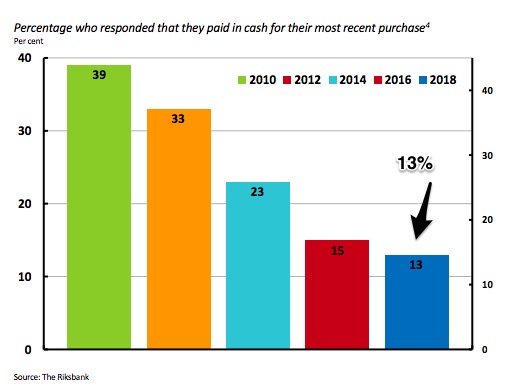

Meanwhile, only 13% of the central bank’s respondents said they had used cash for their most recent purchase:

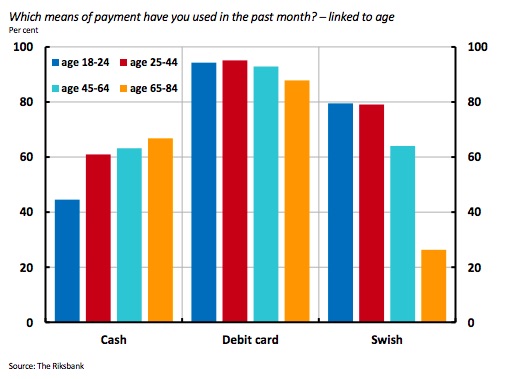

But age did make a difference. Ascending with age, the use of cash was greatest among individuals aged 65 to 84:

Where you lived also mattered. The rural interviews revealed a population that was less enthusiastic about using less cash:

When assessing the trend toward cashless transactions, the Swedish experience suggests we should remember the groups that are resisting the change. We have an elderly cohort who feel discomfort and perhaps an inability to pay digitally. There is a rural population within which 35% might feel negative.

Then, to those considerations, we can add concerns about the unknown. Some have asked about protection from hackers. Others worry about the impact of electrical outages and how a war might impact a new money system. To the list, I would include concerns about diminished privacy.

Our Bottom Line: The Money Supply

Calculating the value of its money supply, a nation usually adds together its currency, its checking accounts, and other relatively liquid deposits like savings accounts. It all matters because the size of the money supply relates to the goods and services we produce. If there is too much money circulating, inflation can become a problem. Too little and we could wind up with deflation. Sort of like Goldilocks and the three bears, we want it to be not too hot, not too cold, but just right.

In Sweden, the population has almost entirely stopped using checks. They have a payment app called Swish and plans for a new e-krona digital currency. In addition there is electronic money, cryptocurrencies, online peer-to-peer lending, and digital systems that bypass banks.

Responding, the Riksbank Governor said, “When you are where we are, it would be wrong to sit back with our arms crossed, doing nothing, and then just take note of the fact that cash has disappeared,” It all reminds us that Ikea’s cashless experiment is about so much more than one store.

My sources and more: Before the experiment, BusinessInsider explained Ikea’s cashless plans. Then after, the N.Y. Times talked about the initial results and its broader implications. From there, to see more of the data firsthand, do go to this report from Sweden’s Central Bank. And finally, for what may be the most crucial part, here are some thoughts from Voxeu about what central banks should consider about cashless economies.

![econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo[1]](/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo1.png#100878)