The Opioid Epidemic and the Labor Force

September 13, 2017

Debating Kenya’s Plastic Bag Ban

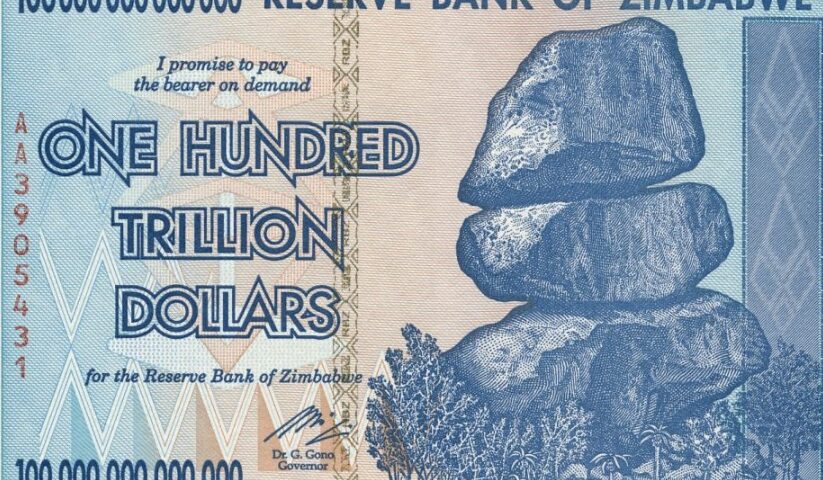

September 15, 2017In 2008, Zimbabwe was the home of the poor billionaire. Stratospheric inflation diminished the value of their currency so much that billions of dollars bought less than a cart of groceries. Zimbabwe’s yearly hyperinflation rate was close to 90 sextillion percent. That’s 22 zeros after the 9.

As a stable currency, U.S. dollars became so popular in Zimbabwe that some had to be laundered. Overused and undersupplied, they were gray and dirty and needed a wash.

As a stable currency, U.S. dollars became so popular in Zimbabwe that some had to be laundered. Overused and undersupplied, they were gray and dirty and needed a wash.

Money laundering in 2010:

Now, some of the same problems could resurface.

Zimbabwe’s New Money

Zimbabwe is still struggling to create a viable money supply. Because their trade balance is negative, U.S. dollars are leaving the country. Add hoarded dollars to the equation and you get cash shortages.

Their most recent solution is the bond note. Valued as equal to the U.S. dollar, the bond note entered the money supply last year. However, when consumers pay for a purchase with a bond note, the price goes up.

In a store, there actually could be three prices. You get the lowest with the U.S. dollar or another dependable currency. With a bond note you could pay 25% more (according to an example in Quartz) while a bank card gets you the highest price–maybe another 20%.

Our Bottom Line: What is Money?

The textbooks say that any commodity can be money if it has three basic characteristics:

- a medium of exchange

- a measure of value

- a store of value

So, green fabric rectangles printed by the U.S. mint are money. Called a demand deposit, your checking account also is money–even when the bank has no actual cash in it. In addition, we could count seashells and Bitcoin as money.

But…Zimbabwe’s bond notes?

My sources and more: I subscribe to and enjoy Quartz Africa for handy updates that relate to Africa’s economies. For more, Newsweek and FT have the story of the new bank note.

Please note that “What is Money?” was published in a previous econlife post.

![econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo[1]](/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo1.png#100878)