Explaining the Health Club Memberships We Don’t Use

January 18, 2015

How Chocolate Chip Cookies Explain Why We Save Less

January 20, 2015Our story starts in a laboratory with some rats. Curious if experiments reflect bias, Harvard professor Robert Rosenthal falsely labeled average rodents as either smart or dumb. His students assumed the labels were accurate.

Where are we going? To how an expectations bias creates a gender gap.

But first, the experiment…

Rats and Expectations

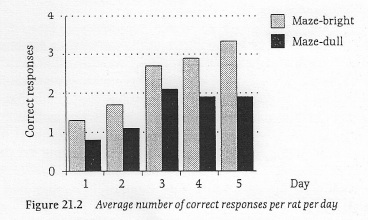

In a series of maze experiments, the “smart” rats’ performance far exceeded what the dumb rats achieved. In addition, the smart rats tended to have more appealing attributes. Tamer, cleaner, more pleasant, they were more likable.

Dr. Rosenthal saw that unknowingly, his students had treated the rats differently. Perhaps because of their affinity for the smart ones, they handled the “bright rats” more frequently and more gently. As I heard Dr. Rosenthal explain in a podcast, touch affects a rats’ performance.

You can see below that the “smarter” rats’ navigated their T-mazes with increasing cleverness.

Based on Rosenthal and Fode (1963)

Dr. Rosenthal’s research took me to female CEOs and corporate directors. Again, expectations play a role. I suspect that when we see more women running businesses, their presence becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Expectations Bias in the Board Room

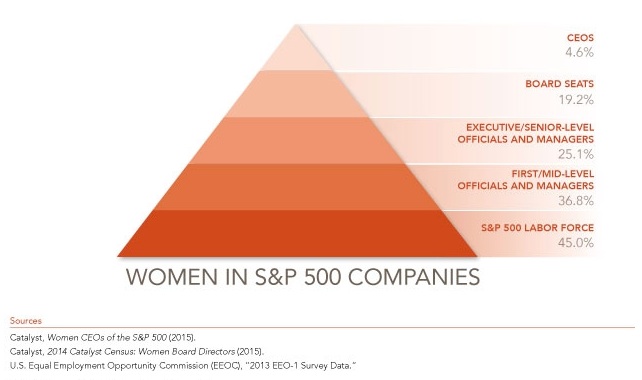

Looking at S&P 500 companies, Catalyst reports that only 23, a meager 4.6 percent of all CEOs are women.

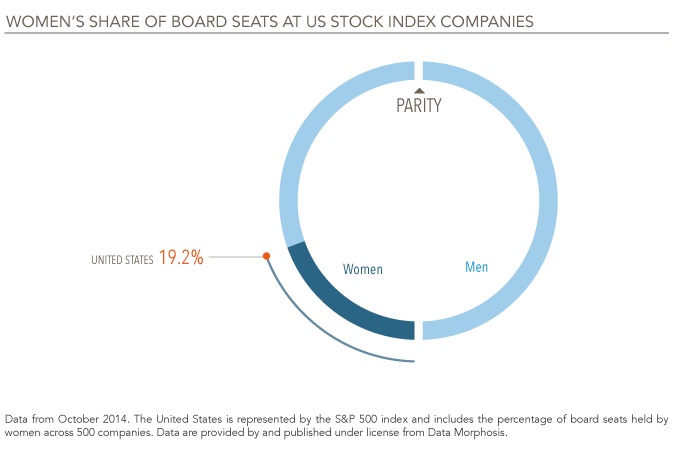

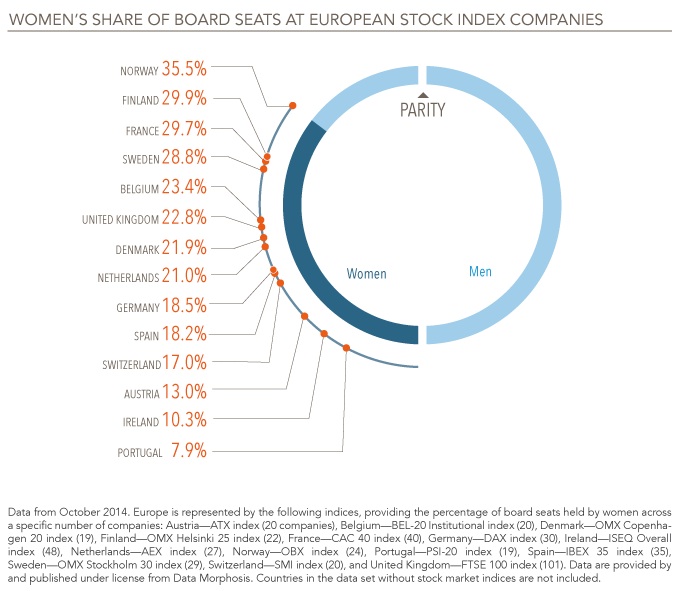

Tweaking our perspective, we can compare women’s share of board seats at U.S stock index companies with the number in Europe.

First, the U.S.:

From: Catalyst

The higher European numbers primarily reflect regulatory mandates:

From: Catalyst

Our Bottom Line: The Khasi

And finally, always my favorite, let’s not forget the message from the Khasi:

Located in Northeast India, the Khasi is a matrilineal society numbering close to 1 million (2011). From birth, women experience a female world. Their households are led by females, businesses are run by women, property can be inherited only by women. When University of Chicago researchers quantified male and female tendencies to compete, the Khasi women got the top grades.

In a Khasi maternity ward, you might hear cheering when a girl is born but, “‘oh okay, he’ll do” for a boy.

Or, if you visit a Khasi home…

“When we visited the Khasi household of a youngest daughter, if a man (obviously the husband) came first to greet us, he always said ‘please wait, my wife (or mother-in-law) is coming.’ And it was the wife who entertained us…while her husband remained silent in the corner of the room, or in the next room.”

And this returns us to why we have so few female CEOs. Whether looking at the Khasi or the U.S corporate world, expectations bias shapes who is at the top.

![econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo[1]](/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo1.png#100878)