How Southwest Became Normal

August 6, 2025

Why Honda Is an American Car

August 8, 2025Recently, Coke’s sweetener has been in the news.

Asking which ingredient tastes better–sugar or high-fructose corn syrup– the NY Times decided to do a blind taste test with participants sampling four colas. One Pepsi and one Coke had been made with sugar and the other two, high fructose. Paying attention to the level of sweetness, to the aftertaste, to the crispness, and to the balance of flavors, they assessed the four colas. Including the paper’s wine critic, and using potato chips to cleanse their palates, the tasters chose the high-fructose Pepsi.

When Coke did some taste tests in 1984, the company created big trouble. Both experiments explain cola competition.

Cola Competition

When Robert Goizueta became Coke’s CEO in 1981, the Pepsi Challenge was growing. Whereas in 1955 Coca-Cola sales were double those of Pepsi, by 1984 Pepsi was behind by only 4.9 percent. Coke responded with Project Kansas. Charged with developing a new taste for Coke, Project Kansas had a tricky task because no one could actually disclose that the goal was a replacement for Coca-Cola. But even with field testing that was somewhat oblique, the results were conclusive. Because participants preferred Pepsi, Coke tweaked its secret formula.

Coke announced its new formula at Lincoln Center in front of an audience of 700 people. All appeared to go well until the questions began. Asked one reporter, “Are you one hundred percent certain that this won’t bomb?” Another said, “… if we wanted Pepsi, we’d buy Pepsi.” And that was only the beginning as the protests multiplied. During a sports event at the Houston Astrodome, people booed the commercials for New Coke.

It did not take long for CEO Goizueta to know he made a monumental mistake. Saying that after the decision he slept like a baby because “I wake up crying every hour,” he brought old Coke back as Coke Classic.

Our Bottom Line: The Prisoners’ Dilemma

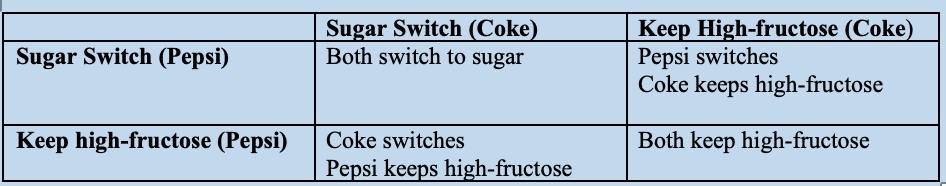

Citing game theory, an economist would say that oligopolies like Coke and Pepsi each have the prisoners’ dilemma. The success of each one’s real sugar decision depends on what the other decides.

Assume two burglary suspects have just been arrested. Interrogated separately at the police station, each one knows that the sentence depends on who confesses.

As you can see in the following diagram, if both confess, they each get three years. And if both don’t confess then the sentence is 6 months. However, denial could bring the longest jail time if the other person tells all:

Because oligopolies like Coke and Pepsi have considerable market power, each one can determine an ingredient strategy. However, like our prisoners, the outcome of the decision also depends on the other party:

The reason is the prisoners’ dilemma.

My sources and more: Thanks to past econlife posts and this NY Times article for today’s facts.

Please note that our featured image is from the NY Times and several of today’s sentences were in a past econlife post.

![econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo[1]](/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo1.png#100878)