Our Weekly Economic News Roundup: From Dot Plots to Chicken Wraps

August 2, 2025

How a Better Peanut Was About More Than An M&M

August 4, 2025Last February, when Wendy’s told us that its digital menu boards would change during the day, customers protested.

Now it’s supermarkets.

Dynamic Grocery Prices

In Norway, prices at Reitan’s REMA 1000 grocery stores change throughout the day. Management says the goal is to keep up with the competition. If they lower their prices, we will too.

In the U.S. though, consumers are not so sure that lower prices are the objective. They believe surge pricing is also a possibility. Similarly expressing concern, lawmakers worry that prices could pop during weather events or holidays or even busy times during the day.

However, digital labels are here already. The CEO of a German-based grocery chain that opened in the U.S. stated the advantages. He said that it facilitates more consistent pricing and lets them control food waste. Also, while Walmart has the labels in more than 400 of its 4600 U.S. stores, it says it has not used them to monitor demand. Like the German executive, they said it could be a time saver.

Dynamic Pricing History

Dynamic pricing is not new. Our airplane fares have always fluctuated.

For retail, in London during the early 19th century, store clerks haggled with customers. Time consuming, the process meant every customer could have a different price.

But then we had the invention of the 19th century department store. Think New York’s Macy’s. It would have been impossible and impractical to train hundreds of employees to negotiate a price for thousands of items. The result? By 1890, one price for each item had become the norm.

With single prices, customer service could blossom as would customer loyalty. We could also have price wars, money-back guarantees, loss leaders, and promotional pricing, Auto dealers tell us that fixed prices for cars cuts buying time by 82 percent from more than four hours to 45 minutes.

Now though, sort of back to where we started, we again have different prices for the same item…even groceries.

Our Bottom Line: Pricing Power

Online, we have airlines and Amazon raising and lowering prices. Now, in supermarkets, we are beginning to see Electronic Shelf Labels for items like Cheerios that can charge each of us a different price.

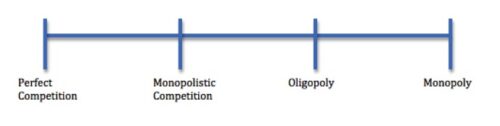

In traditional economic texts, we say that pricing power increases as we move to the right along a competitive market structures continuum. Moving from perfect competition to monopolistic competition, to oligopoly and monopoly, we have increasingly powerful firms. Theoretically, the ones that are more powerful have more control over what they charge instead of the market’s supply and demand.

As always, it is not quite that simple. Whereas traditional textbooks teach us supply and demand graphs, they should add the pricing power that apps and digital menus give them. Depending perhaps on AI, an equilibrium price could perpetually shift in every market structure.

As a result, asking about prices, our answers are increasingly messy.

My sources and more: Thanks to WSJ, here and here, for inspiring today’s post. Then, for the academic lens, this paper had the analysis.

Please note that several of today’s sentences were in a past econlife post.

![econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo[1]](/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo1.png#100878)