On February 25th, we could have celebrated the 110th anniversary of the U.S. Constitution’s 16th Amendment. There was little “hoopla.”

Formally establishing the Congress’s right to levy an income tax, the Amendment was not ratified by seven states (Connecticut, Florida, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Utah, Virginia) while another two (Kentucky, Tennessee) were reported as having said yes but did not.

With the 16th Amendment, our contemporary tax system began. According to the Tax Foundation, the U.S. tax system ranks #22 when compared to the other 37 OECD countries.

Comparing Tax Systems

Comparing tax systems, the Tax Foundation gave Estonia a top score. Meanwhile, France was at the bottom of the list:

Their criteria relate to tax rates and distortions. By competitiveness, they mean the level of the tax rate. Because the Tax Foundation has a center right libertarian bias, they give low marginal tax rates high grades. Then, with neutrality, they are asking if a tax system minimizes the distortions that skew economic activity. As they explain, less neutral tax systems tend to favor one group over another and encourage tax avoidance behavior.

Although the Index’s ranking system reflects their bias, it also lets us use their facts to form our own conclusions.

Below, noting revenue sources, we should look at the individual and corporate income tax, consumption (including the VAT), social insurance taxes, and property taxes. You can see that Estonia depends the most on social insurance and consumption taxes. By contrast, for France, the U.K., and especially the U.S., the proportion is higher for the individual income tax:

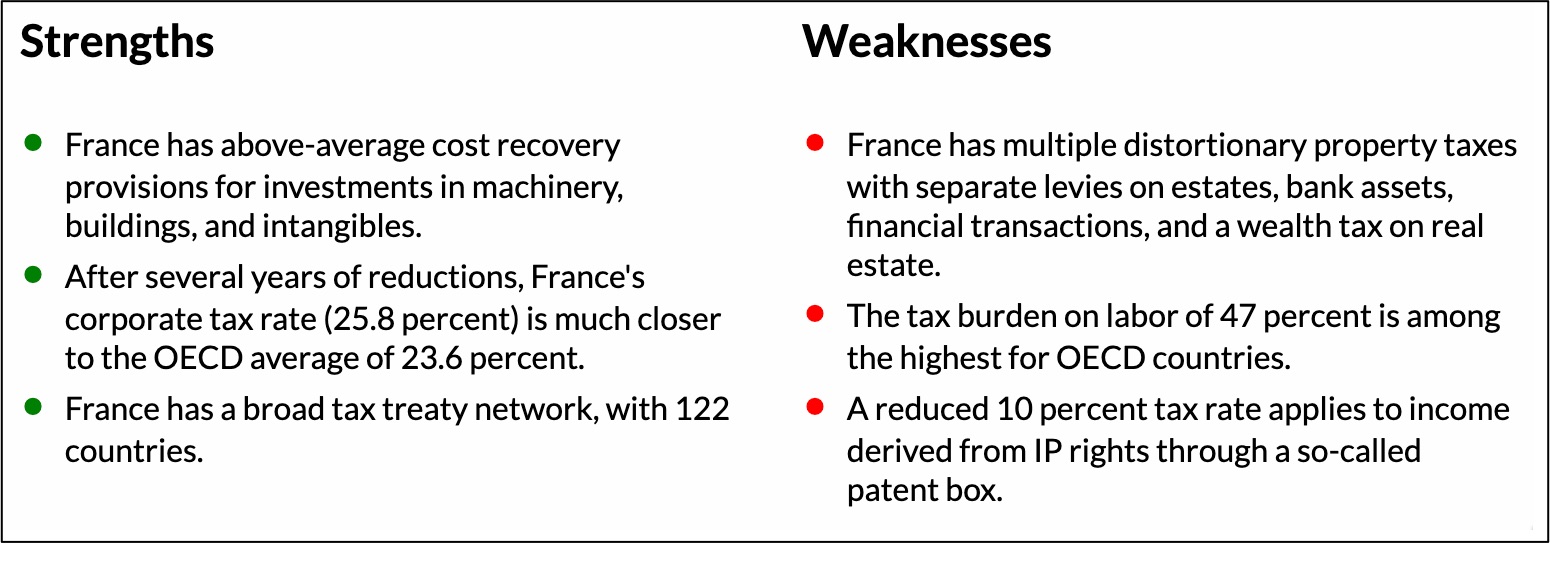

The weaknesses of the French tax system that placed it in last place relate to its distortionary impact. I’ve copied what the Tax Foundation said about the French system:

Our Bottom Line: Tax Approaches

As economists, we look at tax systems through a progressive, regressive, or proportional lens. Then, because of our Tax Foundation focus, we can also ask if we agree with the low marginal rates to which they give the highest scores. If your vision for the virtuous society tilts toward more social programs, then you would give France a higher score. You would also favor progressive taxation that, by definition, collects a higher percent of the income or wealth from the more affluent than from those with less. Correspondingly, regressive taxation involves raising a higher percent from those with less and proportional taxation is the same percent from everyone.

Examples of the three approaches take us to typical taxes. In most developed nations, the income tax is progressive because marginal rates climb with affluence. By contrast, taxes that charge everyone the same amount like the sales tax are regressive. The key here is the percent of your income. If everyone oays the same VAT (value added tax), for example, then, it will occupy a bigger propotion of the income of those that earn less. Meanwhile, the 12.4% U.S. Social Security tax rate below its $160,200 cap makes it a proporitonal tax.

Concluding, we can say that taxes reflect our philosophy and maybe even the reason for some “hoopla” if they achieve the redistribution that you believe in. Or, as Oliver Wendell Holmes said, “Taxes are what we pay for civilized society.”

My sources and more: For tax facts, the Tax Foundation is always a handy first stop (and the source of all of today’s graphics). In addition, I recommend this Throughline podcast that looks at tax history. Please note that I’ve edited this post after publication.