Are We Near Peak Population?

August 15, 2022

How Have Our Chickens Changed?

August 17, 2022The next time you open your refrigerator, please think of it as the final link in a cold chain. And soon, that cold chain will extend to some places where we have not seen it before.

The Cold Chain

Clarence Birdseye

In 1915, after fishing in Labrador’s sub-zero temperatures, Clarence Birdseye was astounded that, weeks later, his frozen fish were tasty. Through his 1926, “quick freeze machine,” he created frozen food history.

Think for a moment of a Birds Eye box of frozen vegetables…maybe Tiny Tender Sweet Peas. Frozen in the factory, a box of peas needs refrigeration to get to the food store, icy temperatures in the supermarket, and then a freezer in someone’s home. By 1944 Birdseye had leased refrigerated box cars as a part of its cold chain and was developing grocery store freezer display cases. However, it was not until after WW II that the cold chain got its final link with the take-off of mechanical refrigerator sales. Now more than 99% of US households have a refrigerator.

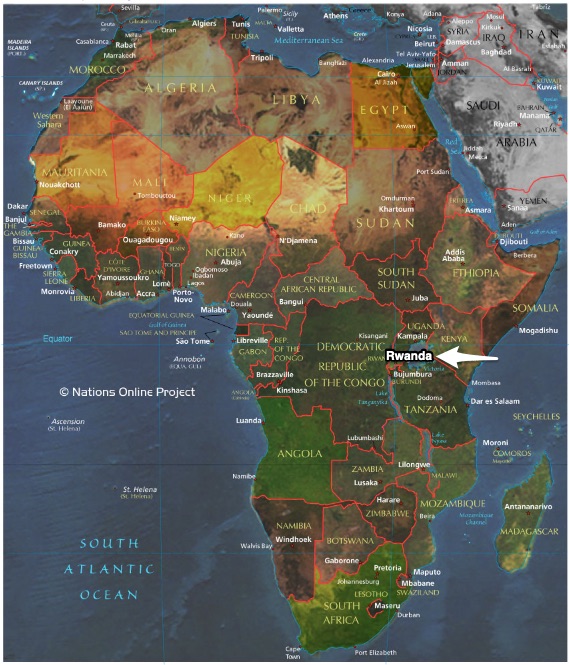

Rwanda

Through a recent New Yorker article, I learned about Rwanda’s progress with its cold chain. One of the poorest nations in the world, Rwanda needs refrigeration to move up the development ladder.

Below, I’ve pointed my white arrow at Rwanda;

As chili peppers, green beans, tomatoes, and milk make their way to Kigali food markets or a flight to U.K. supermarkets, most are too warm. Somewhat similarly, Rwanda has just one ice harvesting machine for the flake ice that fish dealers need.

All of these problems could soon be solved.

Rwanda has announced a National Cooling Strategy. With assistance from the U.K. and the U.N., they’ve established a tech center that will develop and disseminate the refrigeration their nation needs. The goal is to copy the U.S. where green beans run through air chillers and then cold storage or truck and supermarket refrigeration until they reach our forks.

Their solution though is quite different.

One example is the OX. As a small unusually roomy truck, its 4,100 pound capacity is ideal for the Rwanda terrain and economy. The truck is big enough to accommodate the small farmers that rent space and the refrigeration that is planned for newer models. It also can be moved into a 40-foot tall shipping container:

Our Bottom Line: Externalities

In the United States during the end of the 19th century and into the 20th century, the spread of refrigeration through an expanding cold chain had considerable spillover that we would call externalities. Positive and negative, externalities are the impact of a transaction between two parties upon a third uninvolved individual or group.

In Rwanda, a cold chain will affect what producers export and what they sell at home. It influences what people eat and their children’s nutrition. No longer shopping for food each day, households become more productive. Furthermore, when refrigerators boost health by minimizing food-borne disease, they also reduce workers’ sick days. On the downside though, being able to store food at home means you buy more, you waste more, and you increase energy consumption and greenhouse gases.

Most crucially, the upside is how refrigeration glides the Rwandan economy towards the top of the development ladder. It also reminds us that a refrigerator is so much more than an ice box.

My sources and more: Today’s facts come from my past research for Econ 101 1/2 and this New Yorker article. Then CNET added the details we needed about the OX. (Please note that several of today’s sentences were in a past econlife post.)

![econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo[1]](/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo1.png#100878)