Two More Ways That Stores Boost What We Buy

July 7, 2022

July 2022 Friday’s e-links: College Ranking Questions

July 8, 2022At elite schools, “A” seems to stand for average.

The reason is grade inflation.

Grade Inflation

At Princeton, capping the number of As was not working. The faculty was not consistently observing the mandate and students disliked it. So, after a decade of trying, in 2014, Princeton gave up.

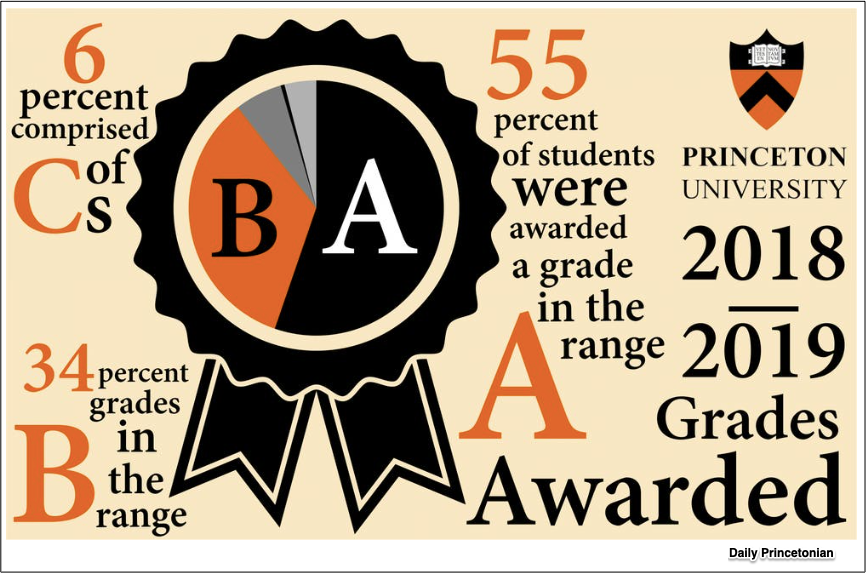

Like prices, grades also rise to equilibrium when you remove a ceiling. Whereas 43 percent of all grades at Princeton had been an A in 1998, the proportion rose to 55 percent for 2018-2019. Meanwhile 34 percent were Bs, C’s were rare, and your chance of getting an F was one in a thousand:

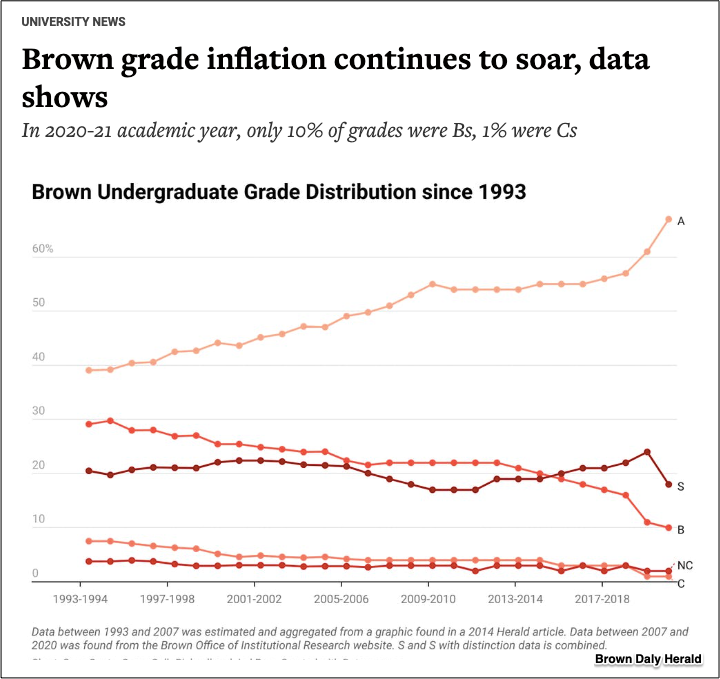

At Brown, students’ grades were similarly inflated. During the 2020-2021 academic year, 67 percent of all grades were As. By contrast, in 1993, it was 39 percent:

For Harvard also, As are average. According to a Harvard Crimson student survey, a majority of respondents had a GPA of 3.7 or higher. (At Harvard, a 3.6 is an A-.):

Researchers that have looked at grade inflation tell us that students are not smarter nor better prepared. They don’t seem to be studying more efficiently or longer. (I did not discover research that explained the cause of grade inflation although one paper indicated more students were graduating because of it.)

Our Bottom Line: Comparing the Components

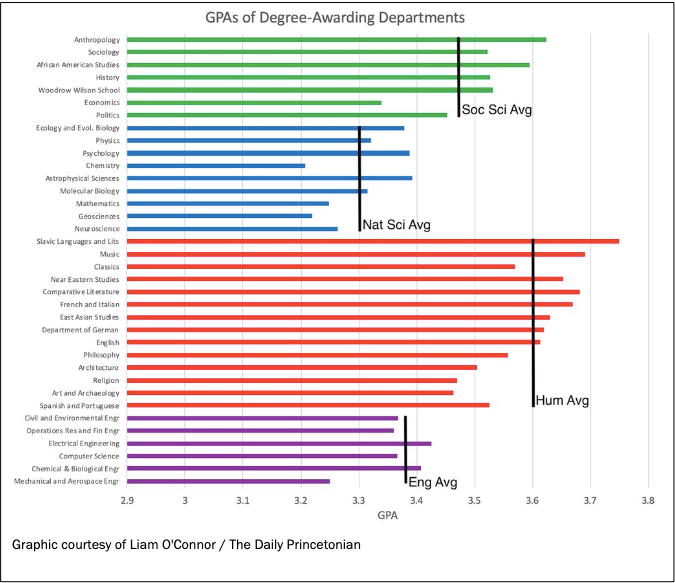

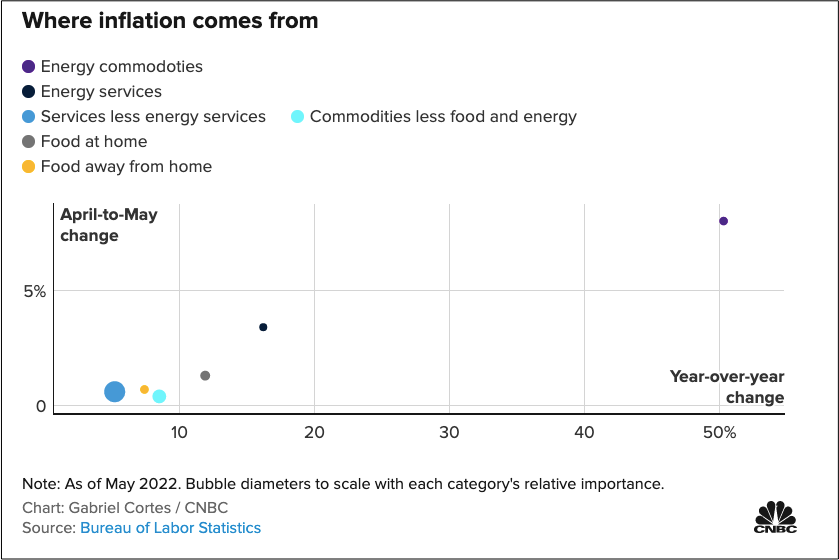

And like the CPI, the components of grade inflation vary:

At Princeton, the inflation rate is highest for humanities and social science classes. Meanwhile,, for prices, it’s “energy commodities” that include fuel and propane that are up close to 50 percent.

My sources and more: This NBER working paper had the recent grade inflation facts as did articles from The Daily Princetonian, The Harvard Crimson, and the Brown Daily Herald.

![econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo[1]](/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo1.png#100878)