Deciding Who Is Rich

September 26, 2021

How the Middle Income Trap Could Ensnare China

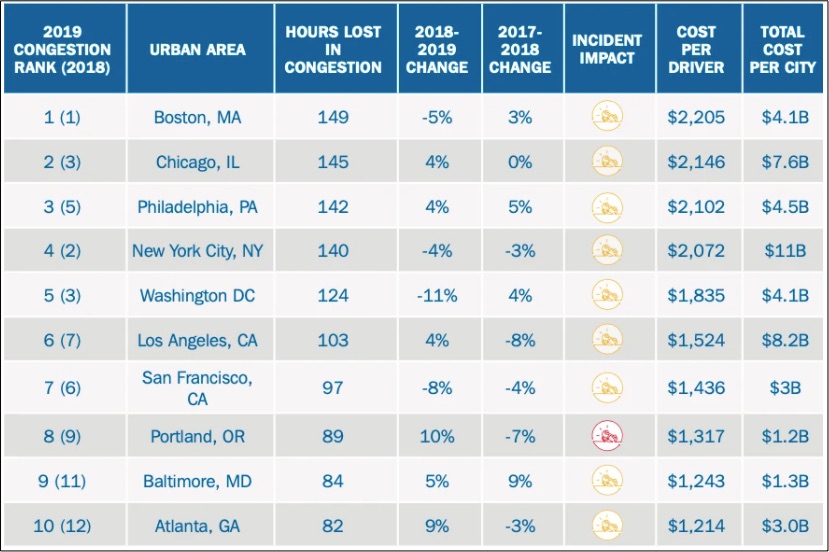

September 28, 2021First in the nation for pre-Covid gridlock, Boston has a #1 award that no one wants. During 2019, Boston’s average rush hour driver lost 149 hours in congestion. In just five years, traffic congestion will have absorbed a month (730 hours/149) from a commuter’s life.

Led by Boston and Chicago, the top five most congested U.S. urban areas also include Philadelphia, New York City, and Washington DC:

https://inrix.com/press-releases/2019-traffic-scorecard-us/

While traffic jams can cost us time at work, a family breakfast, and a morning run, still we resist the best solutions.

Congestion Pricing

Congestion pricing could take us back to the pleasant traffic trickle that Covid created. Once, New York City had a plan. However, it was stalled until Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg gave it a boost. The new infrastructure bill also could provide some of the funding.

Still though, NYC has expressed no precise pricing. In the past, they planned to charge $2.75 per car for driving south of 60th street in Manhattan’s business district. Trucks would have paid more and taxis, an amount related to usage. In another proposal, former Mayor Bloomberg tried for an $8 weekday charge, 6 a.m.-6 p.m., but never got it. Meanwhile, because of surging traffic, London had to raise its fee to £15 a day ($20.56) from £11.50 ($15.76).

Comparing London’s pricing and New York’s original proposal, you can see a massive difference in the pain the plan could inflict.

Conflicting Incentives

Solving congestion is tough because of conflicting incentives.

We say we want less congestion but our urban areas encourage it. In a past paper, parking guru Donald Shoup reminds us that, rather like peanut butter and jelly, urban design and cars need each other. Our cities separate land uses. By locating housing here, jobs there, and shopping somewhere else, they increase travel demand. They also “limit density at every site to spread the city, further increasing travel demand” and “require ample off-street parking everywhere, making cars the default way to travel.”

In addition, we have congestion pricing politics. With constituents that currently pay bridge and tunnel tolls to enter New York City, New Jersey politicians are among the biggest opponents of any new charge. In Virginia, rather than encouraging less driving, the public preference was a new $100 million plus Beltway lane (which transportation experts say just brings more cars.)

Our Bottom Line: Externalities

Last week, it took me an hour to travel from 46th Street to the George Washington Bridge (usually a non-congested 15 minute drive) on the Westside Highway. Smiling, an economist would say it was my own fault. Defined as costs “paid” by bystanders, negative externalities increase for everyone when an extra car enters the highway. Each of us creates rush hour traffic jams. So, we just need to be charged for the externalities we create.

Not only would the charge reduce a negative externality by diverting some of us to mass transit, but it also creates positive externalities by cutting emissions.

My sources and more: Ideal complements, traffic congestion data from INRIX went well with Curbed’s and WSJ’s descriptions.

Please note that this post includes updated versions of sections of previous econlife entries.

![econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo[1]](/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo1.png#100878)