How Covid Changed World Energy Consumption

July 22, 2021

July 2021 Friday’s e-links: From Camouflaged Cookies to Yap Money

July 23, 2021If someone asked you about an X-date or perhaps a “drop dead” date, what would you think of?

It should be the U.S. debt.

On the X- (or drop dead) date, we will touch the debt ceiling. Defined as the limit beyond which the U.S. Congress can no longer borrow money, July 31st is the next X date.

The Debt Ceiling

Why we need to borrow

The U.S. has debt because more money goes out than comes in. In order to cover the difference, the U.S. Department of the Treasury borrows by selling bonds and other similar securities.

Congress needs the money because, on the first of every month, Medicare checks ($35 billion) go out and then on the third of the month, it’s Social Security($22 billion + $60 billion later in the month). Also, the government pays for submarines and highway maintenance, soldiers’ salaries, and owes the President and Vice President their paychecks. Meanwhile, we have trillion dollar Covid support and infrastructure packages.

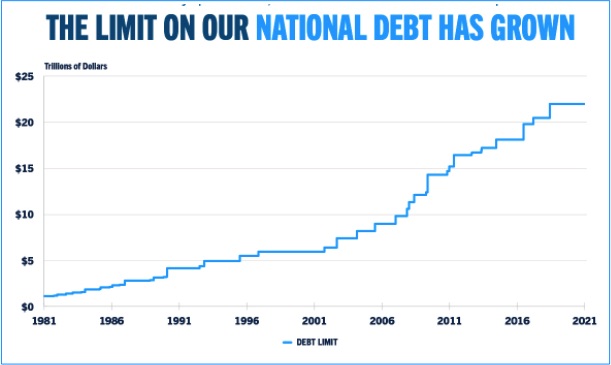

During July 2019, Congress suspended the debt limit. After expiring, it reverts to $22 trillion (the July 2019 limit) plus what has been spent since then. Because the old debt ceiling would not be high enough to permit current spending, the Congress needs to extend the suspension or agree on a new limit. Otherwise, it will not have enough for its obligations.

How we borrow

Whenever the U.S. borrows, someone, somewhere buys a Treasury security such as a bond. The U.S. gets the money. The lender gets the bond–an IOU– and the promise that it will be repaid with interest (for most types of securities).

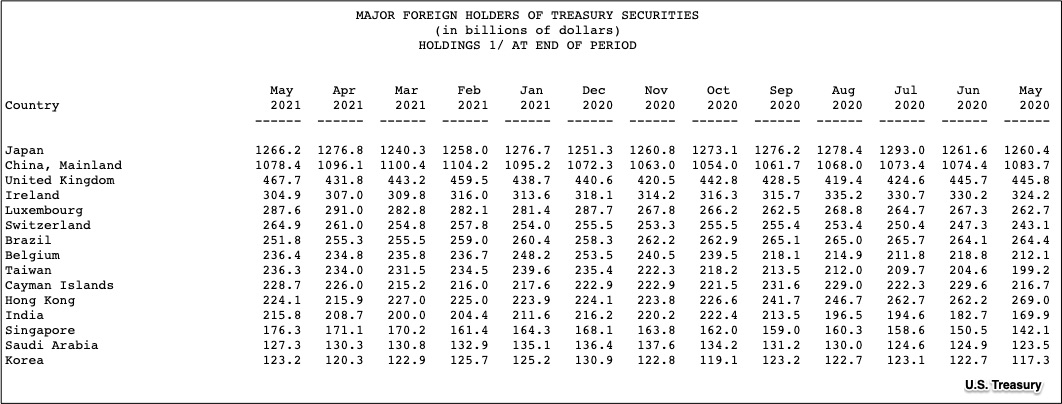

So who has close to $20 trillion in government securities?

Actually, we do. The bonds are held by the public and in government accounts. The U.S. government lends to itself when the Social Security trust fund or Medicare swap their extra cash for bonds. In addition, individuals, businesses, state governments, local governments, pension funds–the list is long–buy U.S. Treasury securities.

The rest of the U.S. debt is held by foreign governments, businesses and citizens with Japan first and China next at the top of the list. The United Kingdom, Ireland, and Luxembourg follow them, and then a long list with Colombia at the bottom for May 2021.

Borrowing history

We have a debt ceiling because of a 1917 law. At the time, the Congress decided it was losing control of the volume of borrowing. To regain power over the federal purse and fiscal policy, they said, “We will decide the maximum amount the U.S. can borrow.” And from that day onward, whenever necessary, they voted to raise the debt ceiling.

It sounds rather simple. But the politics have been unbelievable (actually believable). Repeatedly, different law makers have tried to attach conditions to debt ceiling legislation such as Social Security changes, bombing Cambodia, voluntary school prayer and even a nuclear freeze.

Now again, a battle has begun

A summary

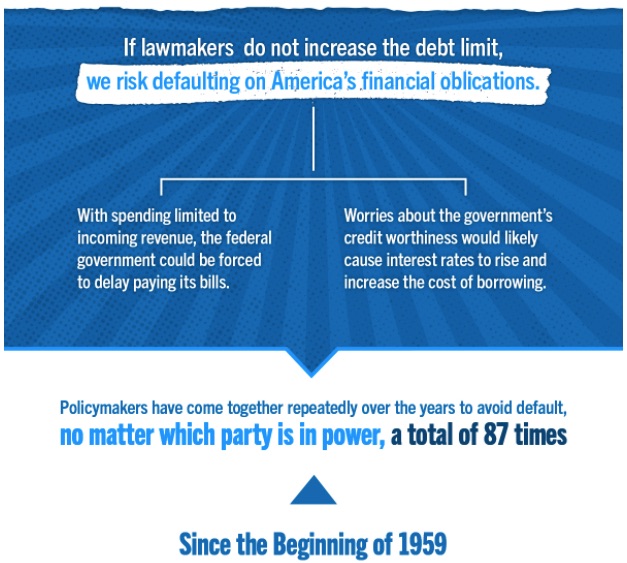

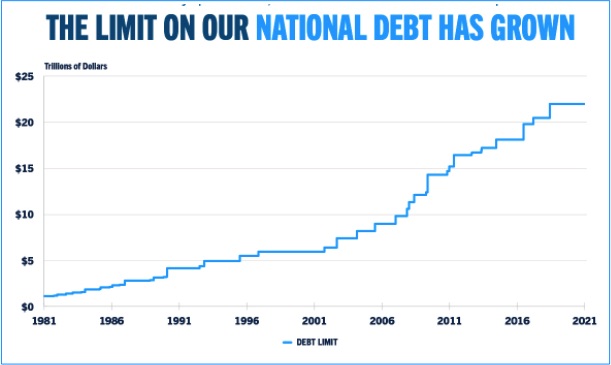

This graphic from the Peterson Foundation has the overview:

Our Bottom Line: Good Credit

Although the Treasury can take extraordinary measures to cover our borrowing obligations, without a new ceiling, we won’t have enough.

Seeing us not meet our obligations by October or November (the projected dates), our first Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton (1789-1795) would have expressed alarm. Manageable borrowing did not bother him. Instead, he believed it helped us establish good credit. With good credit, we could use other people’s money to build infrastructure and other government projects.

Sound familiar?

My sources and more: There are so many ways to look at the national debt. It was handy to go back to econlife posts that I have excerpted and then forward to WSJ for the current situation. In addition, the CBO has some analysis but you can form your own conclusions by looking at the current foreign holders of the debt. Please note that our featured image is the ceiling of the U.S. Capitol rotunda.

![econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo[1]](/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo1.png#100878)