How the 2020 Pandemic Is Like the 1930s Depression

April 12, 2020

Jaywalking and the Tradeoff Between Order and Openness

April 14, 2020An outbreak of yellow fever helped to double the size of the United States. Having lost four-fifths of his troops in Haiti–perhaps 50,000 men–Napoleon decided not to expand his New World empire. Instead, in 1803, he offered the Louisiana Territory to the U.S. for $15 million.

The Louisiana Purchase is just one example of how disease can change the course of a nation’s finances. When researchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco took a look at 15 pandemics, they found a multi-decade economic impact.

Past Pandemics

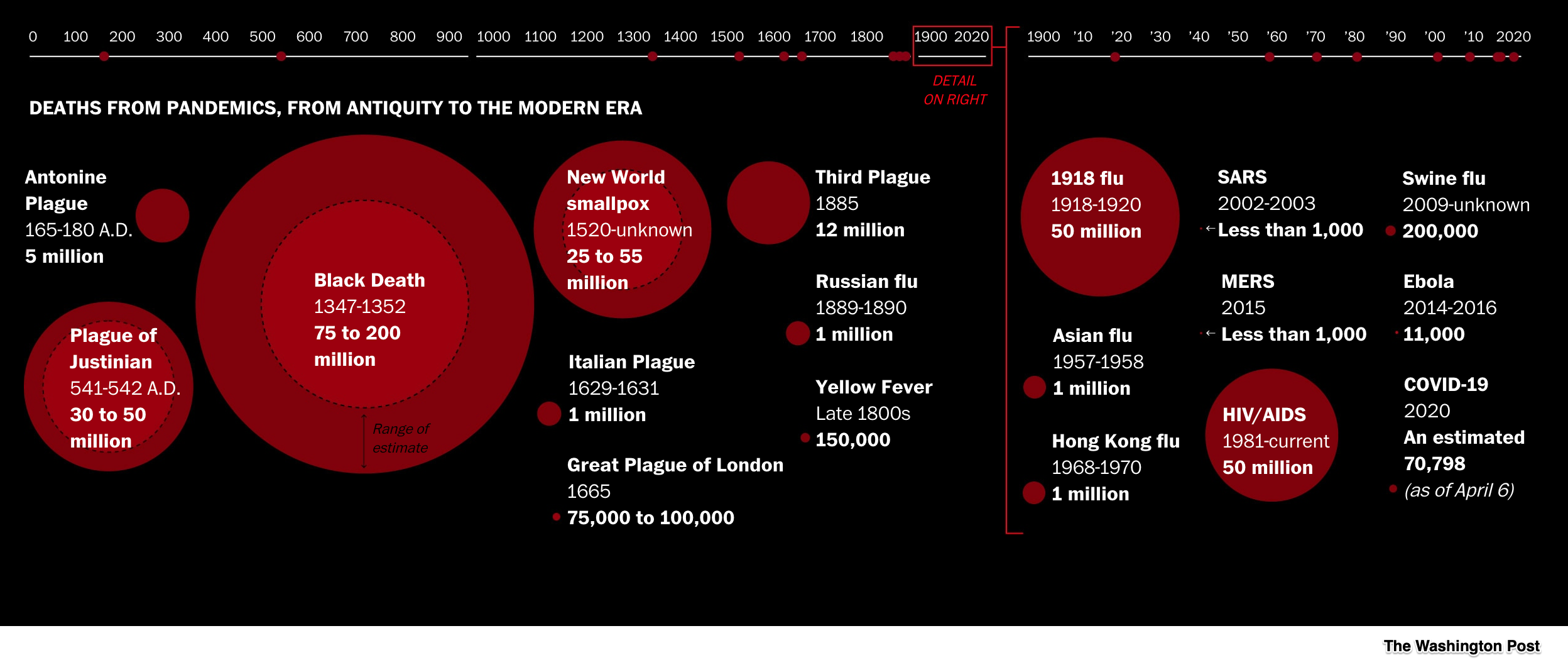

In this Washington Post graphic, the larger circles represent the highest mortality rates for the world’s major pandemics:

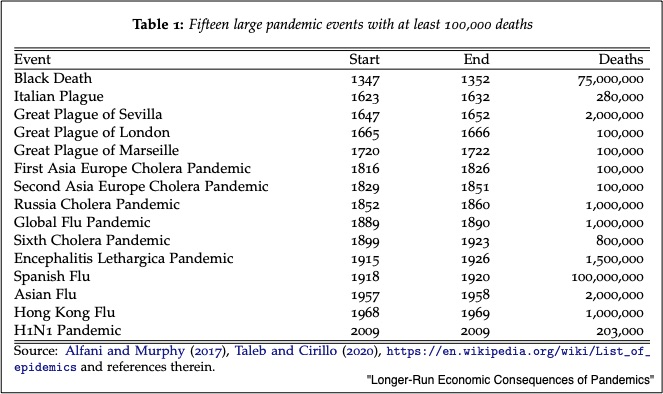

Like The Washington Post’s graphic, the FRBSF paper focused on major pandemics since the 14th century. Below you can see their record of dates and deaths:

The Natural Rate of Interest

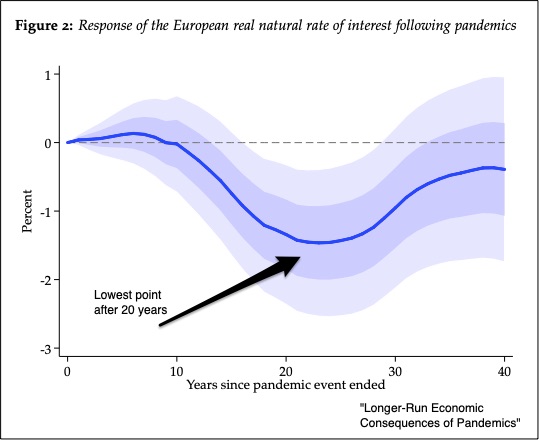

Because of high mortality rates that affect the size of the population and our incentive to save, a pandemic changes the normal path of interest rates. For approximately the 20 years that follow a pandemic, the real natural rate of interest in “aggregate Europe” (France, Germany, Italy, Spain, the Netherlands, the U.K.) declined. Then, after a bottom that is 1.5 percent lower than it otherwise would have been, the rate rises again.

You can see the descent and then the rise:

Wages

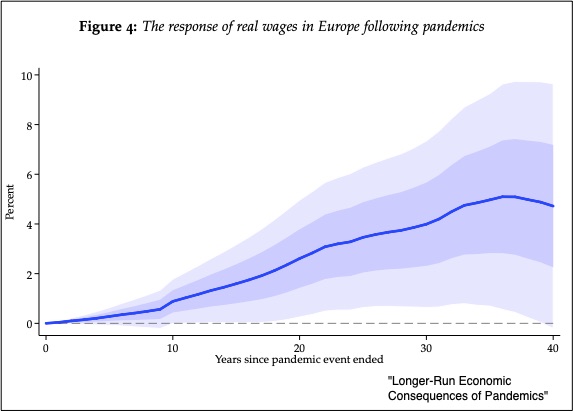

At the same time, a new labor/capital ratio reflects a smaller labor force. However, unlike interest rates, wage rates rise for approximately three decades. Peaking after close to a five percent increase, they dip. Because of the Black Death there was somewhere between a 25 percent and 40 percent drop in the labor supply that propelled real wages up by “roughly” 100%.

You can see the upward response of wages to a pandemic:

Our Bottom Line: Pandemic Economic Impact

As did I, you might wonder how researchers could create a causal connection between a pandemic and a multi-year economic impact. After all, countless variables could affect the results. There could be a depression or a war or a migration. Explaining, the FRBSF said that they see “how the future usually unfolds” and how it evolved after the pandemic. Then, comparing those normal circumstances to pandemic data, and discounting other events, they isolate what the pandemic created. In addition, they tried omitting the Black Death and the 1918 pandemic and still wound up with the same conclusions.

So, where does that leave us? We wind up with lower interest rates, higher wages, and “excess capital per unit of surviving labor” that create “depressed investment opportunities.” The reasons could be “precautionary saving or a rebuilding of depleted wealth.”

My sources and more: The Washington Post had the amazing pandemic history graphic and then we had the perfect complement in the FRBSF pandemic paper. From there, a Project Syndicate podcast and this paper on the 1918 pandemic are possibilities. Finally, here and here, you can read about the impact of the yellow fever epidemic on Napoleon’s troops.

Our featured image shows the burial of plague victims in a (Wiki) miniature from “The Chronicles of Gilles Li Muisis” (1272-1352).

![econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo[1]](/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo1.png#100878)

1 Comment

FOLLOW OUR PAGE https://www.theeconomicpandemic.com/