Whenever my friends and family discover that I have 117,000 (or so) unopened emails, with genuine horror, they condemn rather than compliment me. Now though, a Georgetown computer scientist has explained how my habits could help the entire economy.

Digital Distractions

I should start by saying that I do read my email but I don’t use up time or energy deleting what I don’t read. I just decide which emails to open and when to read them. According to this Georgetown scholar, which and when are crucial.

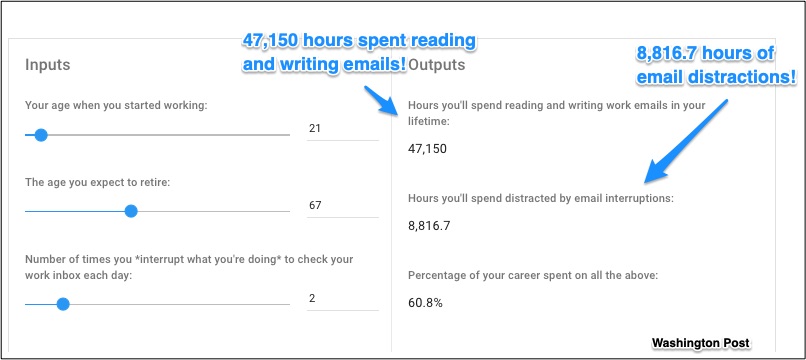

When the Washington Post took a look, it concluded that we consistently divert ourselves from other tasks to read our email. In a lifetime of work, we use more than 47,000 hours:

In his book Deep Work, Georgetown’s Cal Newport hypothesizes that distraction free concentration pushes our “cognitive capabilities to their limit.” In other words, we think best when we focus. He warns us that even just a peek at email eliminates our optimal cognitive focus. And then, because of our “attention residue,” it takes awhile to regain our previous concentration.

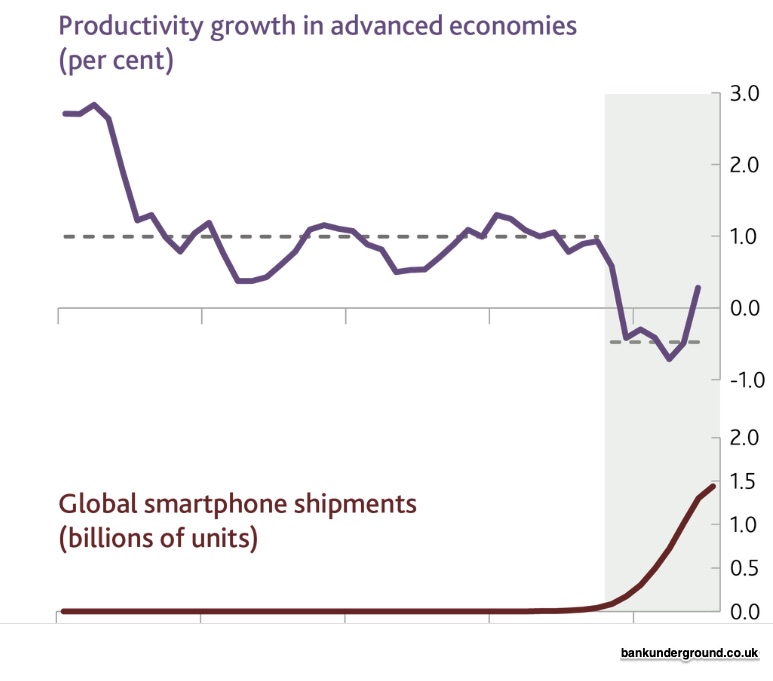

From there, the Bank of England blog takes the malady to the next stage. When we fall prey to digital distraction, it can only get worse. Unable to resist, we experience “continuous partial attention.” The ultimate result could indeed be less productivity and less satisfaction for each of us.

Below, you can see the correlation between diminished productivity growth and increased Smartphone shipments:

But Dr. Newport does have a solution. He believes we should schedule long blocks of time when digital peeks are prohibited.

Our Bottom Line: Market Failure

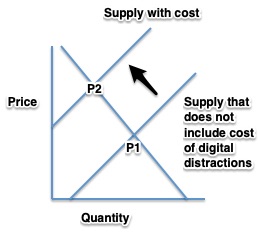

In her guest blog, my former student Michaela Markels insightfully said that digital distractions were the result of market failure. Markets fail when the cost of a negative externality–a negative impact of the activity–is ignored. As a result, the price is too low.

In the following graph, you see that the second supply curve, the one that does not exist, reflects the high cost of the digital distractions. That second curve elevates the “price” and thereby diminishes the quantity demanded. However, the market is at P1. It failed to select the appropriate “price” for a digital distraction:

Just a final thought that reflects the timelessness of distractions. I can’t help but think of Odysseus. Sailing past the irresistible Sirens, he knew he had to be tied to the mast. What is the digital equivalent?

Just a final thought that reflects the timelessness of distractions. I can’t help but think of Odysseus. Sailing past the irresistible Sirens, he knew he had to be tied to the mast. What is the digital equivalent?

My sources and more: Thanks to the Hidden Brain podcast on Deep Work for introducing me to Georgetown associate professor Cal Newport. Next, my search for some statistical validation took me to The Washington Post and to The Economist. From there this Bank of England essay added some substance to the argument.