The Reason For An Income Tax Default (Form)

April 25, 2014

When Did We Get “Tough Love” From the Federal Reserve?

April 27, 2014At the Supreme Court this week, broadcasters sought to stop a small firm from competing against them. Saying it was violating copyright law, ABC led a group challenging Aereo’s business model. Aereo uses tiny antennas to send programming to viewers who can then download and record it. As a result, you can sidestep the payments you might owe for watching program content through cable or satellite or Netflix. While Aereo does not grab the signal for a lot of content, a favorable court decision could open the door to that possibility from Aereo and others. It would, as David Carr suggests, revolutionize how we watch TV.

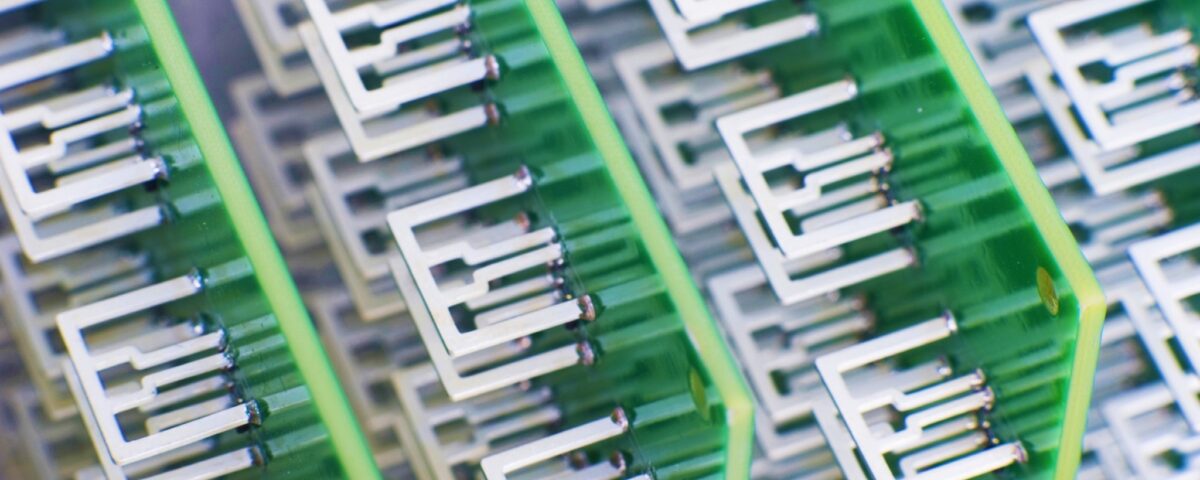

Here is how Aereo works:

Let’s rewind for a moment to 1969 when there was only one telephone company. Called AT&T (a different firm from today’s AT&T), it had a government blessed monopoly for all local and long distance calls. If you needed a phone or phone service, you contacted AT&T. Because the year was 1969, no cell phones existed. The entire phone system needed wires. With some businesses lucrative and others losing money, AT&T said their monopoly facilitated universal high quality service.

Meanwhile, there existed a small firm called MCI that had been started by two young shortwave radio store owners. Hoping to boost business, the company proposed creating microwave phone service between St. Louis and Chicago. Building a series of towers would lengthen the range of a signal by bouncing it from tower to tower. A lengthened signal meant people would want to use, and therefore buy, more shortwave radios.

Soon though, when a venture capitalist named William McGowan joined them, the plans grew more grand. He saw the potential of creating these lines around the country in carefully selected markets. By charging less than AT&T, he could build a market for an alternative phone system. When the FCC authorized MCI to proceed with its St. Louis to Chicago line in 1969, McGowan was ready to generate offspring around the country.

Quickly saying MCI was violating its monopoly, AT&T protested.

In 1982, the question was settled in a federal court in the antitrust case of the century. AT&T’s monopoly was dissolved and firms like MCI could compete with it. The rest of the story is (cell phone) history.

The Aereo case reminded me of MCI. On the one hand you have media giants. On the other side, a small firm charging less is challenging their technology and market dominance. With AT&T and with the Aereo case, technology is upsetting the status quo.

MCI detonated Joseph Schumpeter’s creative destruction. Is Aereo comparable?

Sources and Resources: Starting with David Carr’s NY Times column and then articles in the Washington Post, here and here, you can see the complexity of the Aereo case. For example, if the court decides Aereo is violating copyright law, how can they constrain it without damaging future innovation? Also fascinating, the MCI story is from my book, Econ 101 1/2 (which has much more of the tale). Finally, if you want more on creative destruction, I recommend econlib.

![econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo[1]](/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo1.png#100878)