What We Can Learn From the S&P 500

February 18, 2026Destined for a movie theater–maybe yours or mine–these huge silos in Chapman, Nebraska contain millions of pounds of popcorn kernels:

Movie Theater Popcorn

Our story starts with a jumbo tub of movie theater popcorn. At 130 ounces each, five popcorn tubs were made from one pound of kernels. Since seven of those Nebraska silos hold 15.3 million pounds of kernels, they would have become a whopping 80 million jumbo tubs.

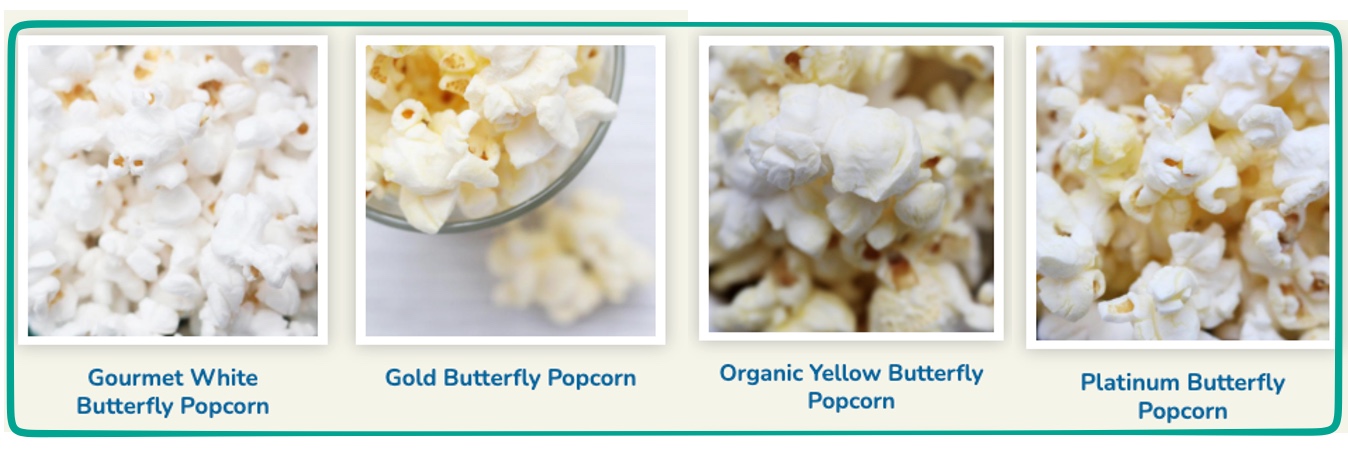

At the movies, we mostly eat butterfly popcorn. Different from microwavable Orville Redenbacher, Jolly Time, and Pop Secret, butterfly popcorn pops bigger. As a fluffier popcorn, it occupies more space in those huge tubs.

Preferred Popcorn, the Nebraska popcorn company that supplies most theaters, had these butterfly popcorn pictures on their website. They sell the 50- to 100-pound bags that larger businesses and distributors buy for theaters:

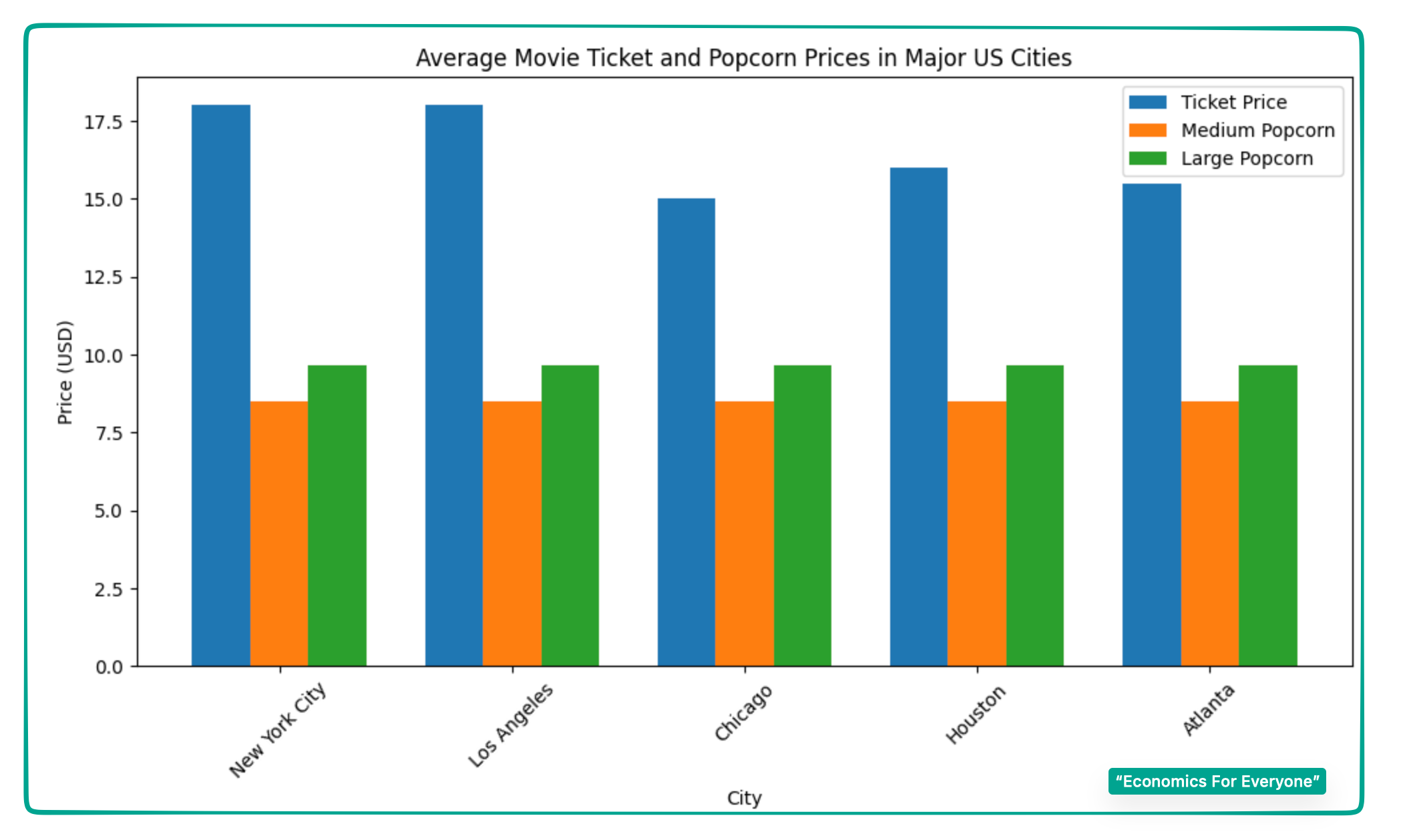

The typical medium bucket of popcorn is sold for $7.99 at the movies. You could buy the same quantity of some similar popcorn for $1.69 or so at your local market. Comparing the price to the cost, the movie theater has a markup that is close to 800%.

The movie theater gets most of its revenue from ticket and food sales. However, somewhere between 60% and 70% (and sometimes more for a huge hit) of the ticket revenue goes to the movie distributor. Consequently, from a $9 ticket, the theater probably keeps from two to four dollars. However, not everyone pays the same ticket price. If you are very young or very old, paying less you generate less revenue.

As a result, the theaters need their snack revenue. In 2018, one movie chain, Cinemark, collected $1.8 billion in ticket revenue but had to pay back $1 billion in fees. Meanwhile, its $1.1 billion concession revenue only cost them $181 million which meant something close to a whopping 84% profit margin.

Our Bottom Line: Elasticity

Referring to how much price changes affect our willingness to buy more or less, elasticity explains why we buy insanely expensive popcorn at the movies. When an item is a luxury, has many substitutes, and costs a large proporton of our income, our response is elastic. In other words, price considerably affects how much we buy. By contrast, for necessities, items with few substitutes, and goods or services that require a small proportion of our income, we are inelastic. In terms of the math, with inelasticity, our change in quantity demanded is a smaller proportion than the price fluctuation. As a necessity with no substitutes, movie theater popcorn perfectly fits the inelastic description.

My sources and more: Through a special section on Entertainment and U.S. Economic History, WSJ’s popcorn story inspired today’s post. Then, for the supply side, our facts came from The Washington Post while the University of Chicago had more sbout demand. Finally, for still more, econlife looked at popcorn here and here.

Please note that several of today’s sentences were in a previous econlife post.

![econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo[1]](/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo1.png#100878)