What a Behavioral Economist Might Say About the Barbie Snub

January 28, 2024

How Hydrox Lost the Cookie Wars

January 30, 2024Some of the bags that airlines lose seem to disappear forever.

But one company in Alabama knows where they go.

Invisible Labor

Lost Luggage Finders

Among the whopping 4.3 billion bags that we check each year, the airlines lose approximately 25 million. Because that’s around 5.7 per one thousand, the odds are good that we arrive with our luggage. Then, even if our bags are lost, there is a good chance we will find them.

However, if your bag is one of the .03 percent that remains orphaned after 90 days, it is destined for another journey. After a company called Unclaimed Baggage buys those bags, they travel to Scottsboro Alabama. There, opening the suitcases, the people employed by Unclaimed Baggage unpack and sell items that range from clothing to Egyptian artifacts.

The business was originally started by a man with an idea. Hearing that a bus company wanted to unload its unclaimed luggage, 50 years ago, Hugo Doyle Owens bought those bags for $300. They quickly sold for much more and the rest of the story is history. He soon became the only lost luggage store–really a huge warehouse.

The Unclaimed Baggage warehouse is a treasure trove (to some of us):

Because we never hear anything about the people that sell our lost luggage, we could say that their jobs are invisible.

Because we never hear anything about the people that sell our lost luggage, we could say that their jobs are invisible.

Wayfinders

One of my favorite invisible jobs is the wayfinder. Wayfinders enable us to…yes… find our way. Hired by airport designers, they are the individuals who use architecture, signage, lighting and color to take us from Terminal A to Terminal D. They create paths for people through angled counters. Or, in a mostly monochromatic space, they could use one color that pops to identify a crucial service.

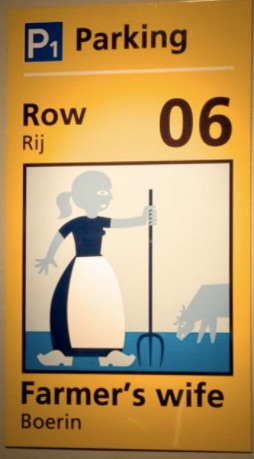

At Amsterdam’s Schiphol Airport, Mijksenaar, a Dutch wayfinder, made it easier for us to remember where we parked. Instead of a letter and a number like B23, they used graphics:

Other Jobs

- The Apple start-up sound has been called rather zen but it wasn’t always like that. Few of us know that Apple sound engineer Jim Reekes realized we needed a “fat C-major chord.”

- For the UN and G7 meetings, the diplomats are in the news. However, we hear nothing about the translators that let them talk to each other.

- Determining how many mikes, where to position them (like high or low in a stairwell), how to manipulate an echo unit, which sounds to combine, countless anonymous recording engineers make decisions about our music.

Our Bottom Line: Fractals

In past econlife posts, the British coastline was our example of a fractal. Explained by a classic paper from mathematician Benoit Mandelbrot, the shorter the ruler, the longer the coast:

Then, as now, it was our way to say the closer you look, the more you see. Defined more precisely, fractals have “self-similarity.” When we zoom into a shape, the smaller one that becomes visible echoes the larger one.

Though not exactly a fractal, the invisible jobs that we see do indeed compose a bigger task. They remind us of fractals because they multiply the size of the job that we originally saw as one unit.

My sources and more: Reading about the lost luggage sellers, I returned to David Zweig’s Invisibles. From there, this Business Insider article on fractals was the ideal complement.

Please note that today’s econlife quoted sections from our past posts.

![econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo[1]](/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo1.png#100878)