In a 1972 experiment–and many times after that–a child and a marshmallow or some other treat were left alone in a room. If the child resisted temptation and ate nothing, they could have two when the adult returned.

For some smiles, do take a 3 1/2 minute look:

Years later, researchers discovered that the SAT scores of children who held out for 15 or 20 minutes were 210 points higher than those who lasted only 30 seconds. Further confirming the significance of delayed gratification, they found that the kids who waited wound up with better jobs and more emotional resilience.

Now, researchers are looking at the results somewhat differently.

Our Newest Marshmallow Test

Visiting Japan, psychology Professor Yuko Munakata observed that her own children had at first begun to eat before their peers until they saw that everyone waited until all individuals were served. Noting the Japanese children’s patience, she realized that U.S. children display similar ability to delay gratification when they see Christmas gifts under the tree but cannot open them.

So, she designed a study in which Japanese and American children had to delay eating marshmallows and opening gifts. For eating, the Japanese youngsters displayed a median wait time of 15 minutes but for the Americans, it was only five minutes. However, the results with the gifts was the opposite. That 15 minute wait was more typical for the American children while the Japanese were at five minutes.

The researchers concluded that the key to waiting was everyday habits–not the children’s “higher level processes” or ability to resist temptations. By contrast, when there was neither a social norm nor a prior practice that delayed gratification, then it is possible that self-control kicks in.

Other Marshmallow Tests

In yet another recent marshmallow retake, researchers changed the original group’s composition. Whereas the children in the 1972 experiment came from a Stanford University preschool with an affluent and educated constituency, this replication changed the numbers and socio-economic group. The children were more varied, the follow-up numbers were larger, and the experiment itself was more consistent. They even looked at how many books were in a child’s home and whether their mothers were responsive. Later, analyzing the data, they made sure to control for income and other variables that might skew the results.

What a difference.

The replication told researchers that family background, the home, and cognitive ability were the facts on which to focus. No longer was self-control the key variable. Instead, they concluded that the ability to hold out is an offshoot of affluence and education. For kids whose mothers had a comparable educational background, those who could and could not delay gratification had similar standardized test scores. And for kids whose lives made them believe they might not get a second treat, it made sense to eat one now.

But we still have more.

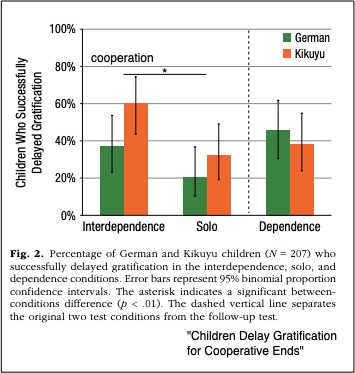

Yet another design has three set-ups and two groups of young children, one from Germany and the other, Kenya. Their goal this time was to determine the impact of cooperation. Separated into pairs, children in the first group were each given a cookie. They were then told that if both ate nothing until the adult returned, each would get a second treat. Meanwhile, in the second group of pairs, the children were “solo.” Anyone who ate nothing until the adult returned got a second cookie. Finally, for the third group, each child controlled the pair. If you postponed consumption, then you and your partner got the second cookie. If you did not, then no one got the second round.

You can see below that cooperation resulted in the highest number of children delaying gratification:

Our Bottom Line: Human Capital

We could say that each of the marshmallow tests takes us to a different side of human capital. The lens for the first marshmallow test focused on self-control and its impact on future success. Now, more recent studies have pivoted to the environment and a socialization variable.

The newest studies remind us that what you look at determines what you conclude. Also though, the common thread that runs through all four versions is human capital. We are truly asking how to optimize our potential…

…And who will nibble before a delayed dinner.

My sources and more: At econlife, here and here, we’ve looked at the original marshmallow test and the follow-up. Now, combining the most recent experiments, described here and here, with the 2020 paper, we get even more insight. As we mentioned in a previous post, still, this New Yorker piece on Dr. Mischel was our best read on the topic. (Please note that I’ve included entire paragraphs from past econlife marshmallow test posts.)