Our Weekly Economic News Roundup: From the Best Country to a Pricey Dog

January 8, 2022

How Fast (Delivery) Became Slow

January 10, 2022Last March, the Georgia legislature debated the to-go cocktail. Because a new law would require the buyer to transport the drinks in a car trunk, they had some concerns. One lawmaker asked, “How do you keep the drink from spilling?” The answer was “Big cup holders.” Another asked if using a motorcycle was okay. It was not. Signed by Governor Kemp on May 5, the bill is now Georgia law.

Elsewhere too, municipalities are debating if they should legalize the to-go cocktail. In many ways, they are having an economic discussion.

Cocktails To-Go

Trying to survive during pandemic shutdowns, eating establishments offered the to-go cocktail. The National Restaurant Association said that alcohol with takeout food could elevate sales by five to ten percent. But first liquor regulations had to change.

And they did.

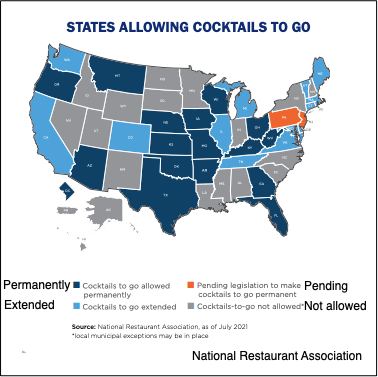

Thirty-nine states recently decided that to-go cocktails would be legal either permanently or temporarily:

Our Bottom Line: Markets and Competition

Traditionally, alcohol has reached you and me through a three-tiered market. It all began in 1933 when Prohibition ended and a “liquor control” commission proposed how to proceed. Their basic goal was state control through a regulatory framework. By separating producers, wholesalers, and retailers, they could prevent the industry from building monopoly power. But they also skewed supply and demand. Cocktails to-go are one way that the system has begun to move toward a freer market.

Cocktails to-go are also upsetting the traditional competition among restaurants, bars, and retailers. As you might expect, liquor stores are concerned about losing sales. More underage drinking is also a worry.

The one likelihood is that the pandemic will accelerate an already crumbling three-tier system.

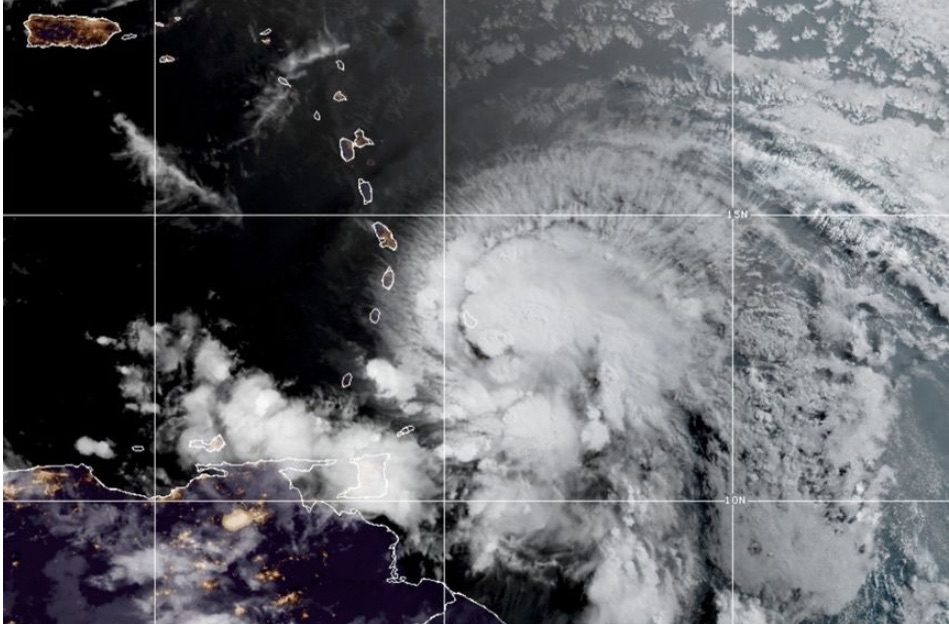

My sources and more: Thanks to Slate Money (which I look forward to every Saturday) for the cocktails idea. While these articles from the NY Times and The Washington Post were helpful, the most precise facts came from the National Restaurant Association and this law blog from Nixon Peabody. (Please note that our featured image is from Matt Brooks/TWP via The Washington Post.)

Also, I edited my initial post. Having originally included John D. Rockefeller as someone who helped to lead the 1933 liquor control commission, I concluded (contrary to a NYS report and a law journal) that, close to death, JD Rockefeller did nothing to shape the liquor industry. I eliminated his name from the post.

![econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo[1]](/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo1.png#100878)