The Problem With a 5-Star Review

August 31, 2021

When the Cost of a Plane and a Wait Are Similar

September 2, 2021In a 1972 experiment–and many times after that–a child and a marshmallow or some other treat were left alone in a room. If the child resisted temptation and ate nothing, they could have two when the adult returned.

For some smiles, do take a 3 1/2 minute look:

Years later, researchers discovered that the SAT scores of children who held out for 15 or 20 minutes were 210 points higher than those who lasted only 30 seconds. Further confirming the significance of delayed gratification, they found that the kids who waited wound up with better jobs and more emotional resilience.

It’s possible, though, that they got something wrong.

A Second and Third Marshmallow Test

Described in a 2018 paper, researchers changed the group’s composition. Whereas the originals were based on a Stanford University preschool with an affluent and educated constituency, the recent replication changed the numbers and socio-economic group. The children were more varied, the follow-up numbers were larger, and the experiment itself was more consistent. They even looked at how many books were in a child’s home and whether their mothers were responsive. Later, analyzing the data, they made sure to control for income and other variables that might skew the results.

What a difference.

The replication told researchers that family background, the home, and cognitive ability were the facts on which to focus. No longer was self-control the key variable. Instead, the ability to hold out is an offshoot of affluence and education. For kids whose mothers had a comparable educational background, those who could and could not delay gratification had similar standardized test scores. And for kids whose lives made them believe they might not get a second treat, it made sense to eat one now.

Now, in yet another version of the marshmallow test, researchers have again shifted their perspective.

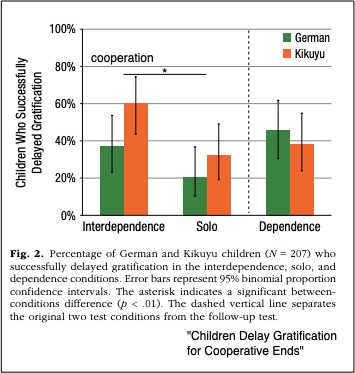

The newest design has three set-ups and two groups of young children, one from Germany and the other, Kenya. Their goal this time was to determine the impact of cooperation. Separated into pairs, children in the first group were each given a cookie. They were then told that if both ate nothing until the adult returned, each would get a second treat. Meanwhile, in the second group of pairs, the children were “solo.” Anyone who ate nothing until the adult returned got a second cookie. Finally, for the third group, each child controlled the pair. If you postponed consumption, then you and your partner got the second cookie. If you did not, then no one got the second round.

You can see below that cooperation resulted in the highest number of children delaying gratification:

Our Bottom Line: Human Capital

We could say that each of the marshmallow tests takes us to a different side of human capital. The first marshmallow test was about self-control and its impact on future success while the second injected the impact of your environment. Now, the third inserts a socialization variable. Asking if cooperation boosts results, the answer was a resounding yes.

The common thread that runs through all three versions is human capital. We are truly asking how to optimize our potential…

…And whether we should nibble before a delayed dinner.

My sources and more: At econlife, here and here, we’ve looked at the original marshmallow test and the follow-up. Now, its newest version provides still more insight. As we mentioned in a previous post, this New Yorker piece on Dr. Mischel was our best read on the topic. (Please note that I’ve included entire paragraphs from past econlife marshmallow test posts.)

![econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo[1]](/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo1.png#100878)