Weekly Economic News Roundup: From Tipping to Vacations

March 4, 2017

Why Grade Inflation is a Problem

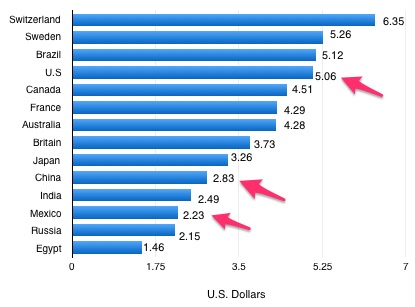

March 6, 2017Based on the January 2017 Big Mac Index, we can get the most burger for our buck in Egypt. At the equivalent of $1.46, an Egyptian Big Mac is less than one-third the $5.06 U.S. price. On the other hand, a Big Mac in Switzerland would require (a whopping) $6.35 in U.S. dollars.

Where are we going? To what the Big Mac tells us about purchasing power and tax proposals.

Purchasing Power

Internationally

The Economist’s 2017 Big Mac Index shows us what a $5.06 U.S. Big Mac would cost if you traveled around the world. Looking at the 14 countries I selected from the Index, you can see Big Macs are relatively inexpensive in China and Mexico:

The Dollar Price of a Big Mac in Selected Countries

Domestically

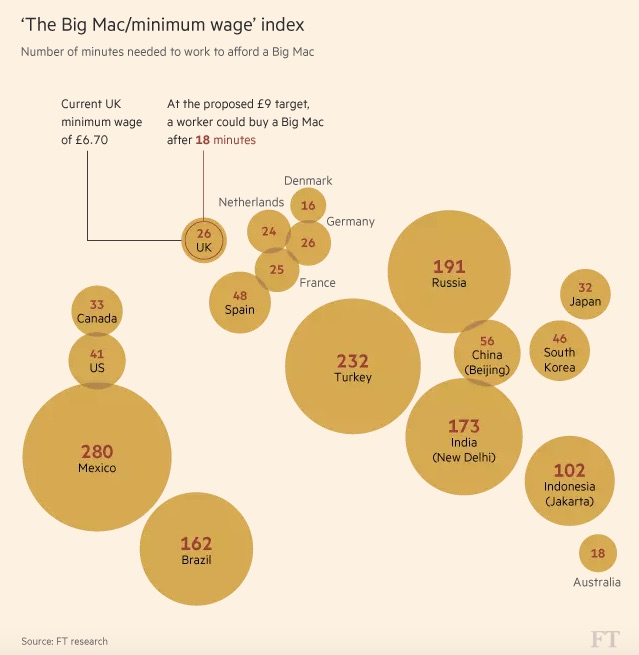

The price of a Big Mac can look entirely different through the eyes of a minimum wage worker. An employee who is paid the U.S. federal minimum wage needs close to 45 minutes of work for a Big Mac. In Mexico, it would take more than four hours:

Our Bottom Line: Big Mac Prices and Tax Proposals

The price of a Big Mac can give us insight about the purchasing power of different currencies. A Big Mac will cost you $5.06 in the U.S. and 19.6 yuan in China. However, converting $5.06, you get 34.93 yuan–more than its 19.6 yuan price. With 34.93 yuan you could get 1.78 Big Macs. What we have then is an undervalued yuan that makes Chinese goods more attractive in world markets.

But a currency’s purchasing power can change. Better at making certain items, a country can charge less. Others try to make exports more attractive by intentionally undervaluing their currency. We can also add the currency impact of domestic instability or a sinking commodity price.

Those currency changes take us to recent proposals for a U.S. “border adjustment” tariff that proponents say would strengthen the dollar. Taking the next step, they conclude that a stronger dollar would eliminate the pain consumers will feel from higher import prices. But the Big Mac Index shows us that foreign exchange rates are not quite that predictable. As a result, we cannot necessarily assume where a tariff will take the relative value of a currency.

But we can look at the Big Mac Index for some clues.

My sources and more: As always, my source for the newest Big Mac Index was The Economist while the Guardian and FT had the minimum wage data. Do note please that in my Bottom Line, I did use an explanation from a previous econlife post. And also, McDonald’s makes their Maharaja Mac with chicken in India.

![econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo[1]](/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo1.png#100878)