The Surprising Cost of a Minimum Wage Hike

January 27, 2026Several weeks ago, at a birthday party, I found myself seated next to a Hermès sales associate. Of course, having written about the Birkin bag in econlife posts, I was delighted. Subjecting the poor woman to a barrage of questions, I discovered an expert who had actually been one of the few employees selected to visit the workshop in France where the bags are made. Rather than any economics of scarcity, her perspective was quality. She explained, with massive pride, the workmanship embodied by each inch of each handbag. Convinced that she was partially right, I wanted to sidestep disagreement.

But there is so much more.

Luxury Economics

Whether it’s a Birkin (or Kelly), a Patek Philippe, or a Ferrari, scarcity creates demand. In the past, we’ve attributed the demand to Thorstein Veblen’s conspicuous consumption. As he explained, the most affluent like to display their power through items that have no value except to display their wealth.

The buyer though is only the beginning.

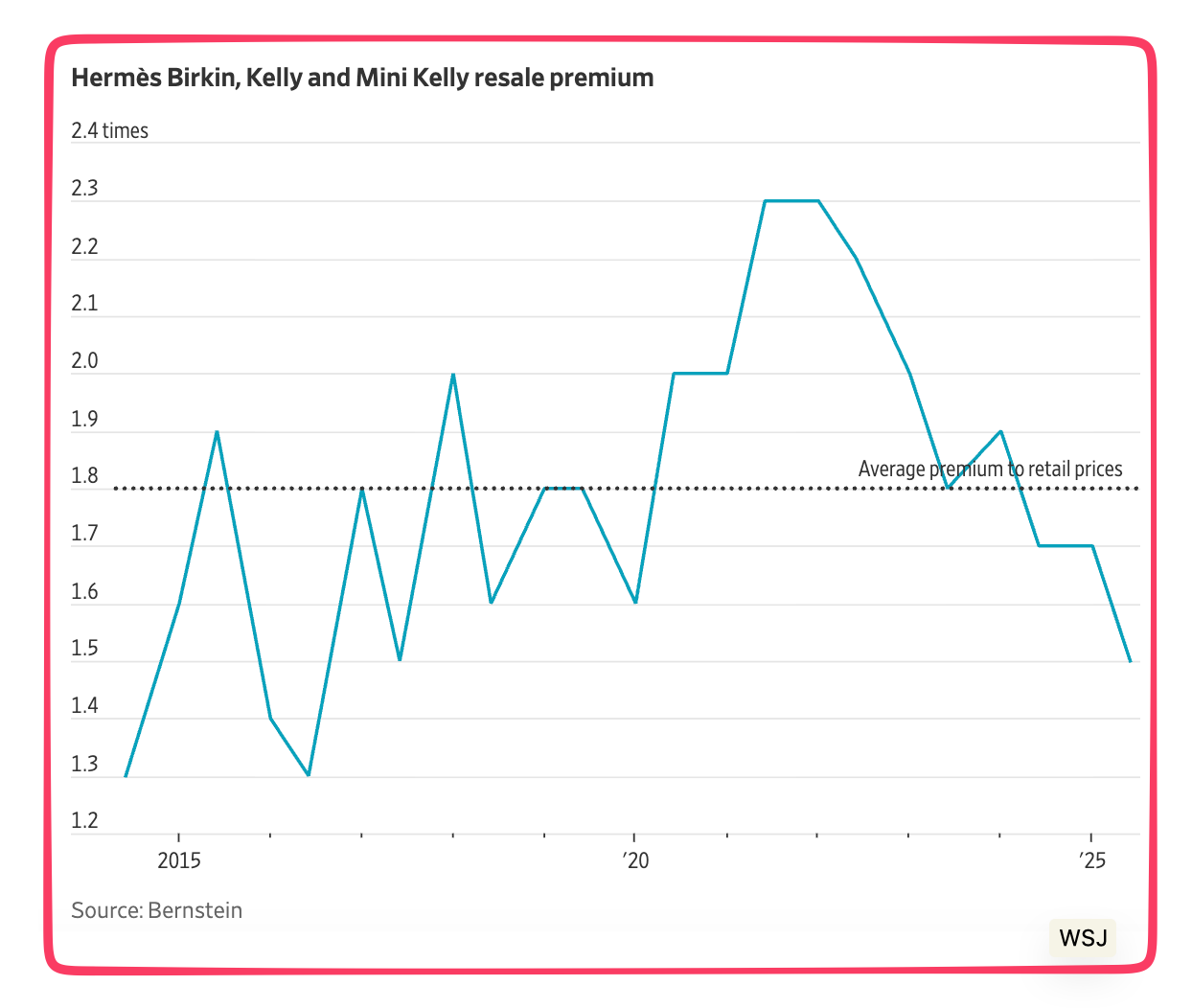

From there, the firm uses the aura it creates to boost sales of other items. Hermès reputedly looks at a customer’s buying history before selling her a Birkin. Ferrari wants to know how many other Ferraris you own. Similarly, Patek Phillip checks the buyer’s watch collection. In addition, the Birkin phenomenon reputedly reduces paid advertising expenses and skyrockets secondhand auction prices. Knowing that “the story” enhances sales, Hermès, Patek Philippe, and Ferrari are among the few that figured it out.

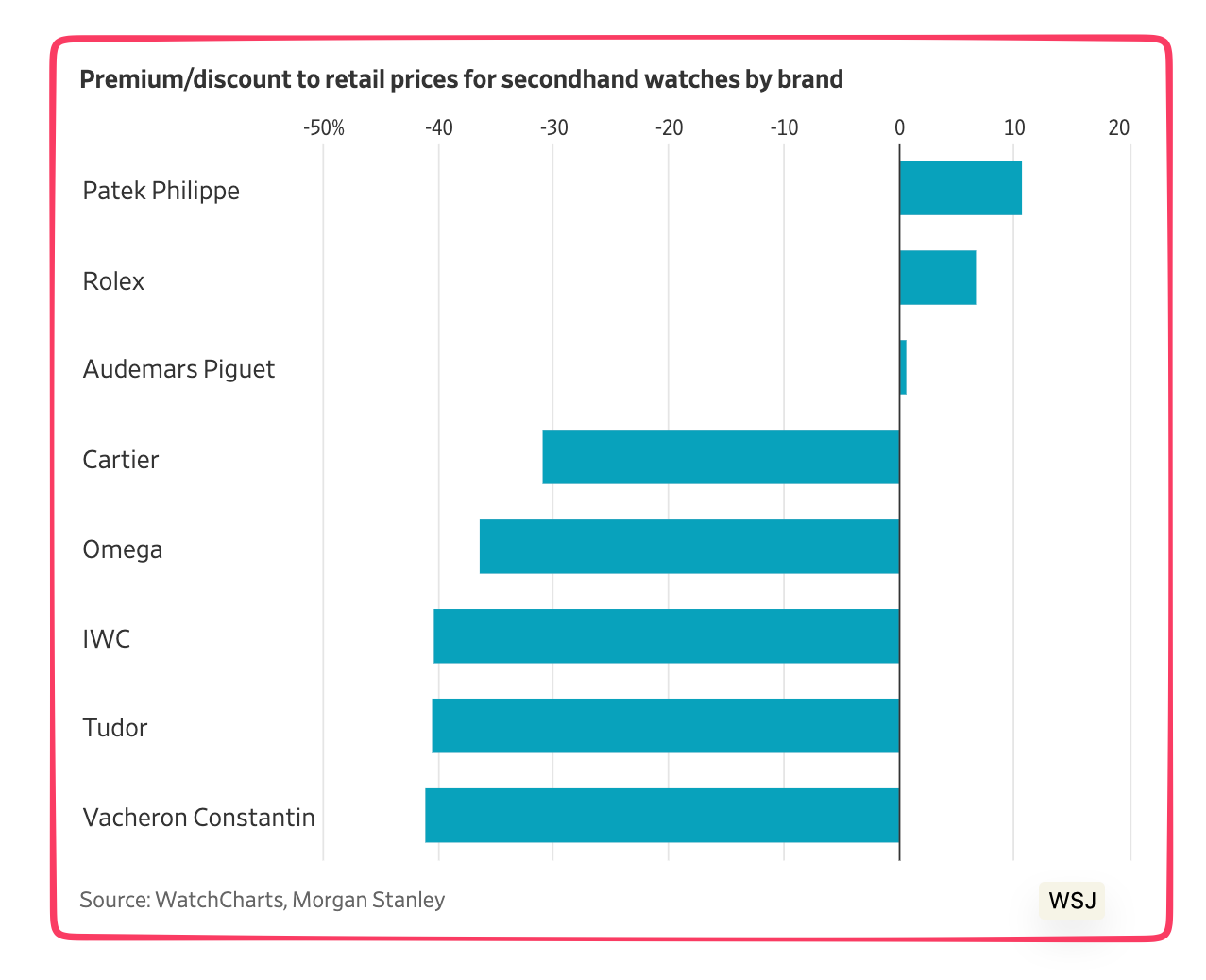

The numbers explain secondhand watch markets. Patek Philippe produces 72,000 watches annually while Cartier makes close to 720,000. Consequently, those secondhand Patek Philippes go for 11% more; Cartier’s are 31% less:

Our Bottom Line: The Power of the Market

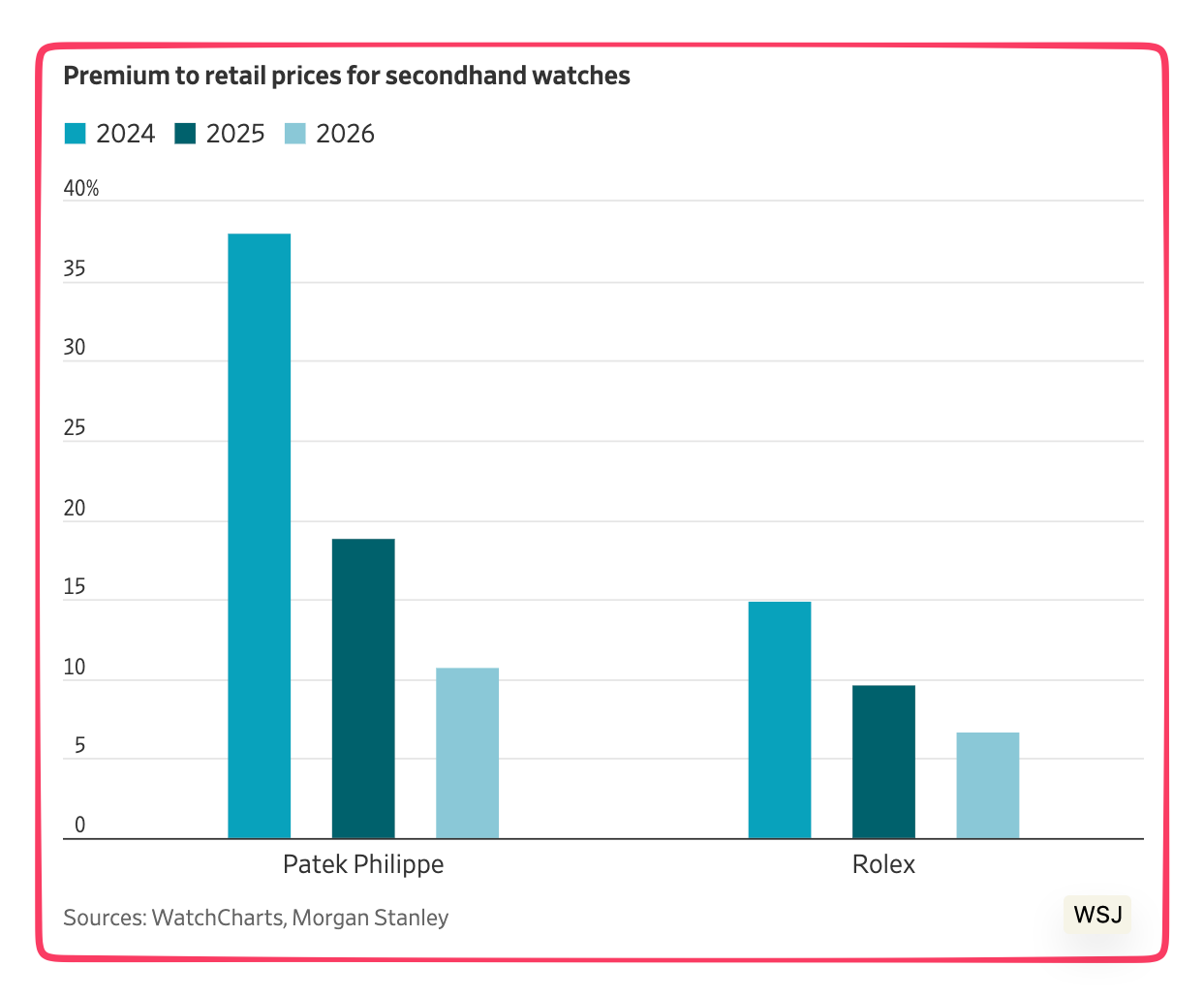

With a WSJ headline telling us that, “Wait List for Birkin or Rolex Gets Shorter, ” we see again that “Trees don’t grow to the sky.” In the article, WSJ cites tariffs as one reason for the drop in secondhand demand. Having nudged prices so high, the tariffs made it impossible for secondhand markets to keep up. When secondary markets fall behind primary price pops, then we have less value retention.

At this point, I always like to return to the power of the market. Controlled by many of us rather than just a few, the intricacies of luxury market supply and demand have changed. Maybe markets went too high or Covid had an impact. Or there could be more secondhand liquidations. Whatever the reason, we might just be returning to a determinant of demand. When utility declines, so too will the demand for an item.

Secondhand watch prices pull closer to retail:

And so too have “pre-owned” purse prices:

My sources and more: Thanks to WSJ for its Birkin update.

![econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo[1]](/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo1.png#100878)