Just Ask Jenna Looks At Our Herd Mentality

January 15, 2026

January 2026 Friday’s e-links: A Good Book

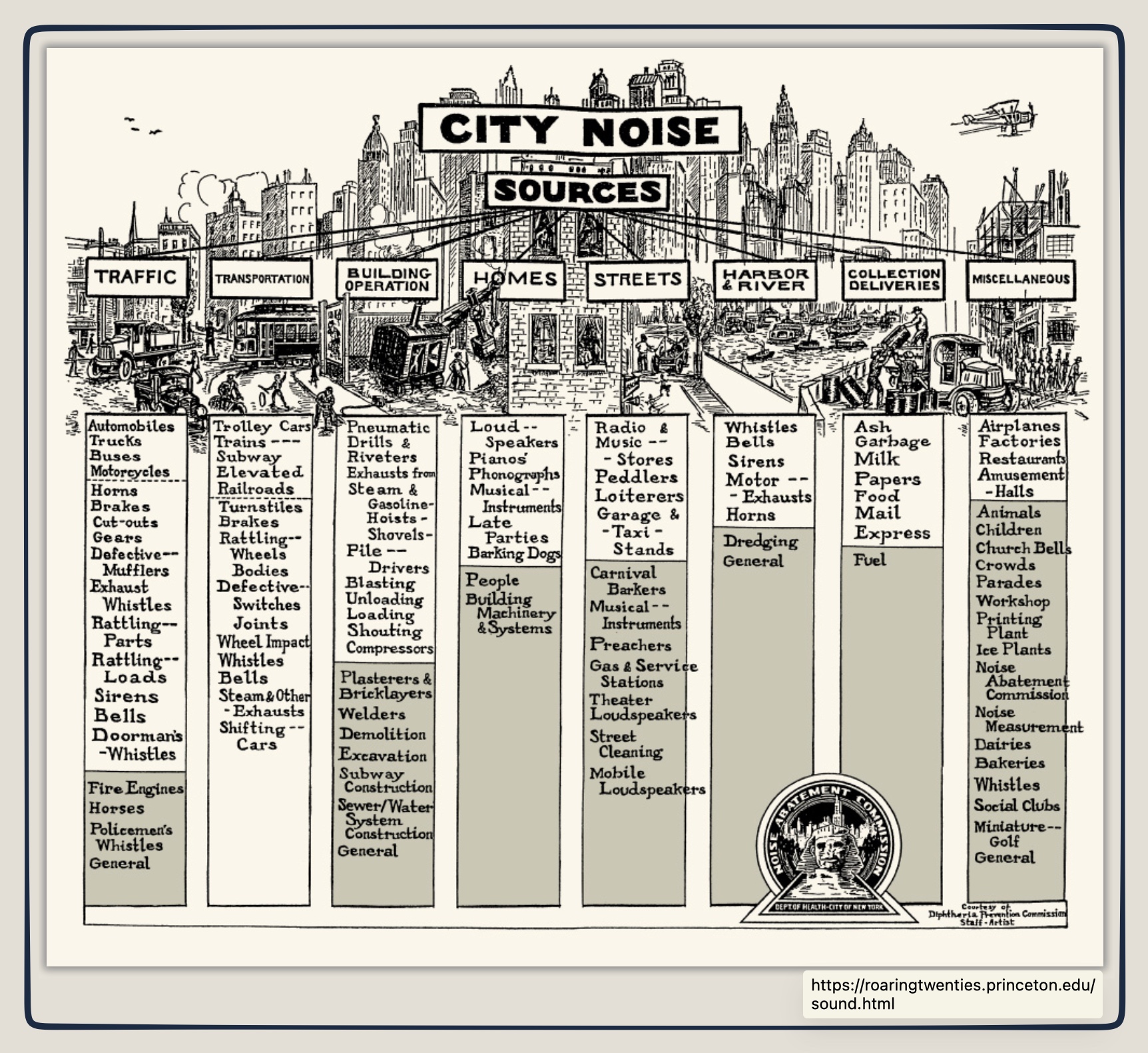

January 16, 2026In 1932, the NYC Noise Abatement Commission received a letter from Mr. N. Schmuck of 137 Milton Street in Brooklyn about the noise from a nearby pickle factory. Other 1930s noise complaints included early morning ice deliveries and “ear splitting shrieks of whistles” from boats on the East River.

Referring to the 1920s, Princeton Professor Emeritus Emily Thompson, gave us a longer list:

Noise, though, is more than a nuisance. It has a dollar cost.

The Cost of Noise

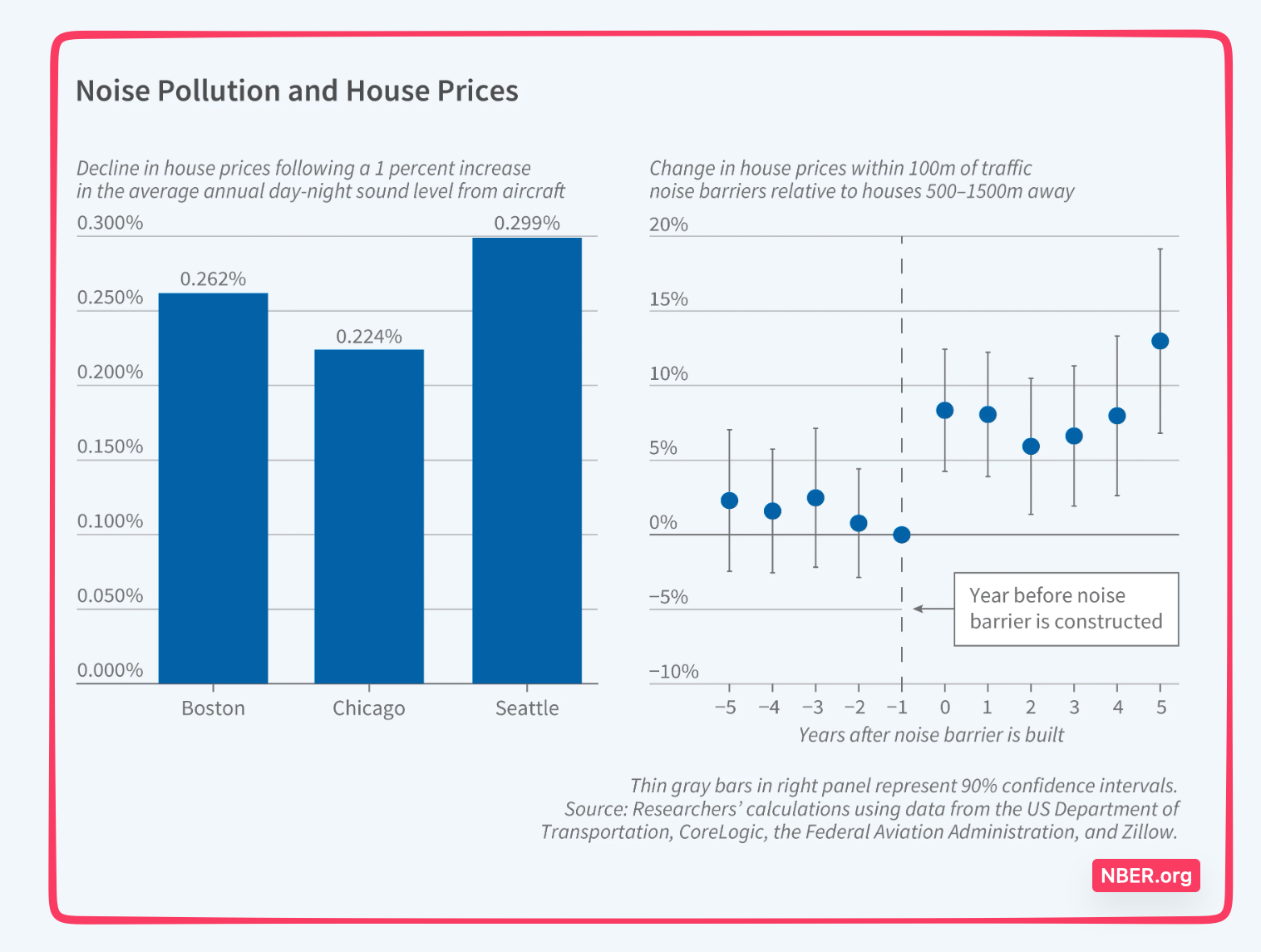

Taking the next step, economists looked at the impact of aircraft noise on home prices. Focusing on homes near Boston’s, Chicago’s, and Seattle-Tacoma’s major airports, they traced the ups and downs of plane volume. Then, in a separate study but with similar results, economists documented the impact of highway noise barriers:

The aircraft study combined plane data with housing price fluctuations. Using close to 85,000 housing transactions between 2011 and 2015, they observed the “willingness to pay for a one-decibel reduction.” For Seattle, it was $221, Boston, $152, and in Chicago, $104. They also noted that lower income households, able to pay less, suffered more.

Somewhat similarly, covering 1990 to 2022, the highway study cited the impact of noise barriers. Homeowners located within 100 meters of a noise barrier saw the value of their property ascend an average of 6.8%. Also, though, the change in value related to the quality of the barrier.

Predictably, as economists, from there, they estimated that the cost of traffic noise pollution was a whopping $110 billion burden on the economy.

Our Bottom Line: Negative Externalities

Hearing about noise, as with all pollution, we can say that we have a negative externality. All we mean is that an “innocent” third party is bearing some cost from someone else’s activity. At this point, economists like to tell us that if producers had a higher cost for whatever they made, then their output would decrease, and that third party would suffer less.

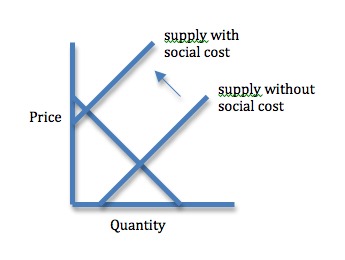

On the graph you can see that equilibrium quantity is higher than where it would be if the market accounted for the extra cost. As with any supply curve, when production cost increases, supply diminishes:

This is where the tragedy of the commons enters the picture. Whether looking at noise pollution, an overgrazed pasture, or overfishing, people have the incentive to abuse publicly shared resources. Privately benefiting from our behavior, we tend to ignore the impact of everyone using the resource together. The result is the negative externalities created by a tragedy of the commons.

What to do? Nobel Laureate (actually Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences) Elinor Ostrom (1933-2012) might have believed that communities could formulate their own solutions. In a wonderful 2009 Planet Money podcast, she explained why. Perhaps more practically, a Pigouvian tax (on noisy vehicles) makes sense.

My sources and more: I recommend heading straight to Princeton Professor emeritus Emily Thompson’s website for sounds from the 1920s. Not quite as interesting, my NBER Digest email had the noise pollution research. Then we returned to this econlife post.

Please note also that several of today’s sentences were in a past econlife post.

![econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo[1]](/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo1.png#100878)