When Is a Dork Like a Fang?

July 27, 2025

6 Facts: What It’s Nice To Know About Tariffs

July 29, 2025At econlife, we’ve looked at the history of light.

During the 1770s, in Virginia at night, this gentleman had none:

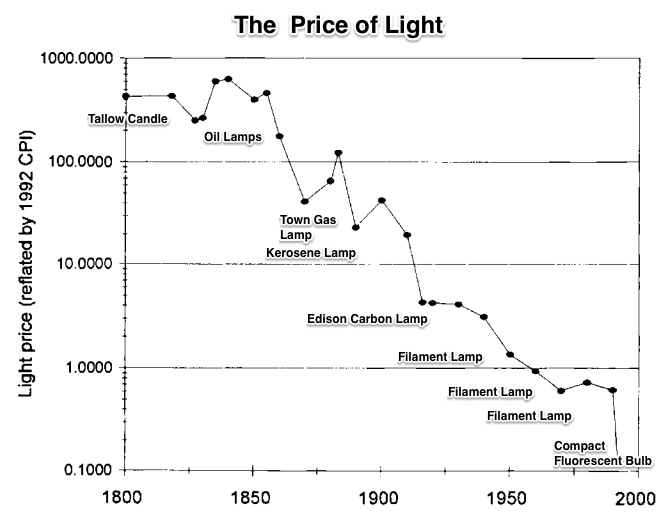

In 1800, a typical middle class urban household spent approximately 4% of its income on the oil, lamps, matches and candles that illuminated their lives. Nobel laureate William Nordhaus estimated that today we use less than 1% of our income for approximately 100 times as much artificial illumination.

So yes, the price of light has plunged:

Letting us spend much less for so much more, light helped to propel GDP growth.

Letting us spend much less for so much more, light helped to propel GDP growth.

Firewood also fueled the GDP.

Firewood Economics

During the first half of the 19th century, firewood powered steamboats and locomotives. While at work manufacturers needed wood, at home we used wood for heat, light, and to cook. In 1860, firewood was the source of 85% of the total energy consumed in the U.S.

Between 1790 and the 1830s, firewood’s share of the GDP/GNP increased from 18% to close to 30%. But by the 1880s, replaced by coal, firewood dropped to less than 5% of the GDP:

Most crucially firewood prices correspond to economic growth. When firewood was an industry necessity, and the economy was growing, then its price went up. Consequently, firewood prices suggest estimates of 19th century growth. Also though, as coal use grew, still firewood prices remained elevated. As a result, we wound up with “a pattern of rising prices and falling consumption for fuel wood, and falling prices and rising consumption for coal.” The reasons could come from the supply side where we had less wood and more coal.

Our Bottom Line: Firewood Demand

Through firewood history, we can see two basic demand concepts.

Determinants

As economists, we know that demand determinants shift our curves. Typically, when income goes up, so too will demand. Similarly, if we want more of a certain product, then demand will increase for a related item as with peanut butter and jelly. By contrast, for substitute goods and services, we would see curves move in opposite directions. Buying more pears because someone suggests they boost longevity could decrease demand for apples, and move its curve to the left. Similarly, when coal became more popular, demand for firewood diminished,

Normal and Inferior Goods

While we just said that demand increases when our income rises, there is one exception. For an inferior good, we buy less when our income goes up. And when coal use soared, firewood became an inferior good.

So, where are we? I suspect we can just say that economic insight is everywhere–even in our firewood.

My sources and more: Thanks to the Bloomberg Odd Lots podcast for alerting me to the firewood paper.

![econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo[1]](/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo1.png#100878)