How Norway Got A Longer Coastline

June 28, 2023

What Buffet Economics Says About All-You-Can-Eat

June 30, 2023Our age can be biological or chronological.

Or it could be South Korean.

Calculating Our Age

South Korea

In South Korea on Day 1 of your life, you would have said you were one year old. Then, on the next January 1, South Korean babies turn two. Consequently, if you were born on December 31, the next day you could celebrate your next birthday. Just 2 days old, you would become a 2-year-old.

Actually, it all makes some sense when we look at culture. Whereas Japan and China stopped observing the ancient practice of basing age on a shared calendar, South Korea never made the switch. They retained a tradition that supported the connection between age and social status. Meeting people, to determine what you call them, South Koreans needed to know their age. The ancient system made this easier.

However, all changed yesterday when a new law kicked in that uses the international age standard.

As you might expect, some individuals want to retain the past while others do not. One young man liked remaining 30 because, in his 20s, he got less respect. By contrast, a young woman says that knowing she will be in her 20s for 2 extra years, she worries less about getting married.

Chronological Age

As we all know, chronology, based on a 365-day calendar, is the most typical way to calculate our age.

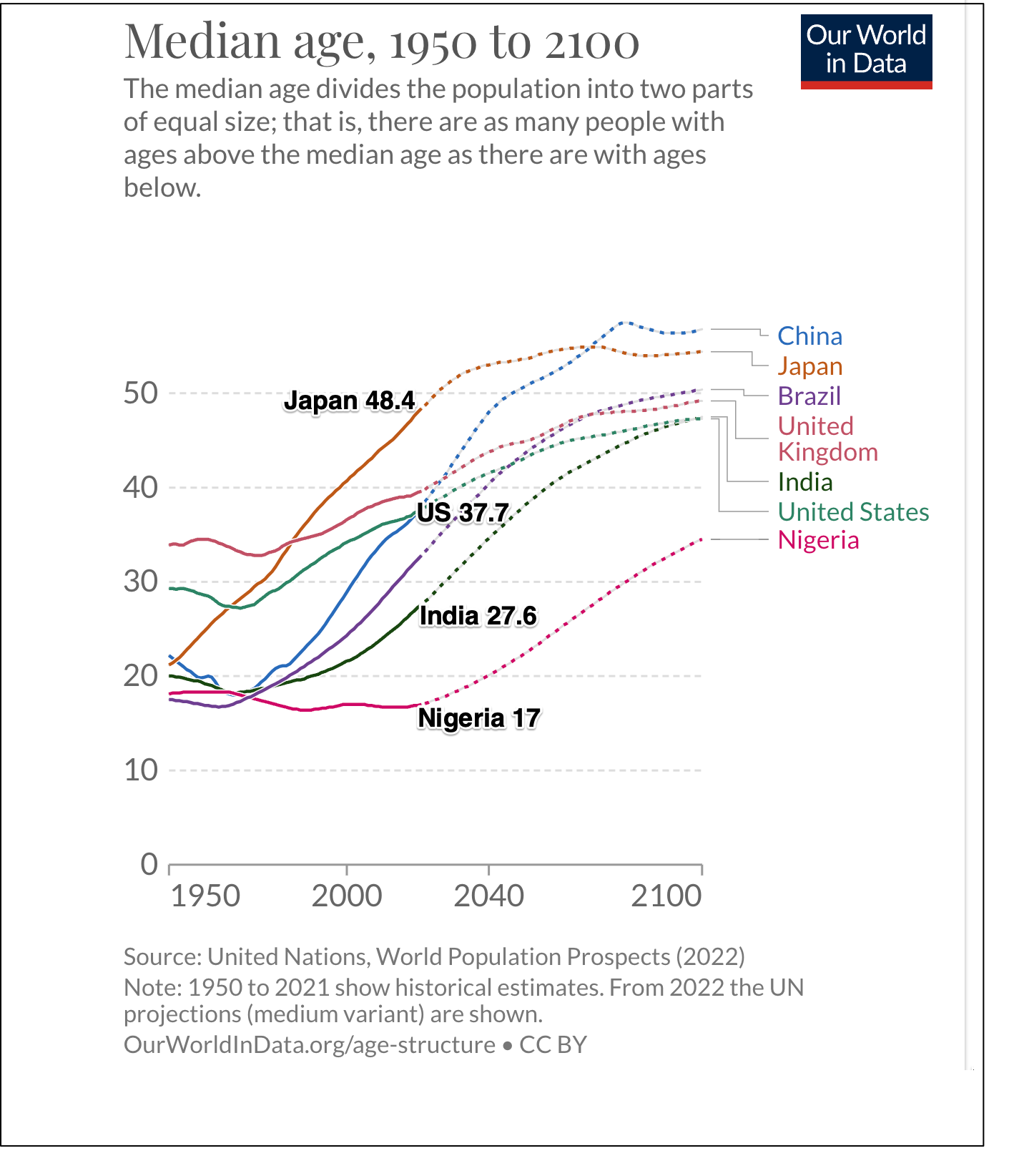

Calculating age the same way, we could see that most of the world is growing older. Below, I noted the 2021 median age for 4 countries, the year before projections start. (Had we included South Korea on the graphic, at 43.4, their median age during 2021 would have been near the top. However, I am not sure which numbers they used to compare their median age with everyone else.):

You can see that, chronologically, we are living longer. But we are also biologically younger because of longer life expectancy.

Biological Age

One Yale Medical School professor, Morgan Levine, says we can calculate our biological age with nine biomarkers. Several years ago, she told CNN that they included, “blood sugar, kidney and liver measures, and immune and inflammatory measures.”

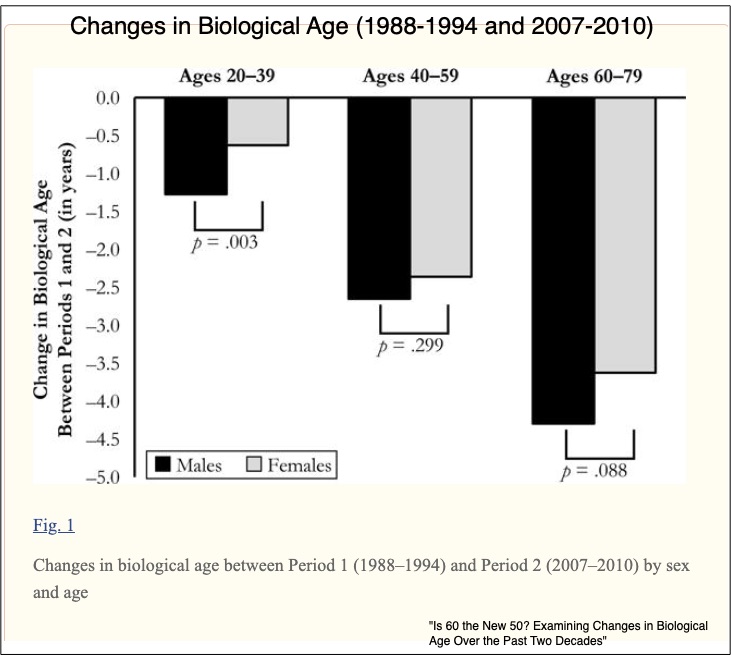

A paper that Dr. Levine co-authored quantifies the decrease in our biological age. For example, between the two time periods, 1988-1994 and 2007-2010, the decrease for women aged 60-79 was 3.63 years:

As we would expect, she takes us beyond the averages to the differences and policy implications that relate to age, gender, genes, health habits, disease…the list is long. All though remind us that, as we considered yesterday through the length of Norway’s coast, statistics can be arbitrary. Also, as with the Norwegian coastline, the closer you look, the more you see.

Our Bottom Line: Dependency Ratios

In previous posts, we’ve used an old-age dependency ratio, the OADR (number of people 65 and over as a percent of the labor force) to convey the impact of a growing elderly population. The basic idea has been that an increasingly larger older population will impede economic growth because of a proportionally smaller labor force. In other words, more young people will have to work harder because of all of those old folks who don’t work.

Maybe not.

A recent WSJ article tells us that some baby boomers remain in the labor force during their 80s. As you might expect, the octogenarians that continue to work are “high-powered” professionals, in business and finance. In addition, more of us have a younger biological age.

My sources and more: Yesterday, I learned how South Koreans calculate people’s age from the WSJ What’s News podcast. Next, for more detail, I went to this WSJ article and then, for the big picture, Our World in Data. However, if you really want to learn more about biological age, this paper is a start with this article about the 80-year-olds that work, the ideal complement.

Please note that several of today’s sentences were in a previous econlife post.

![econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo[1]](/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo1.png#100878)