Our Weekly Economic News Roundup: From Sick Benefits to Healthy Tea

April 8, 2023

Six Facts About Global Poverty and Wealth

April 10, 2023To prepare a tasty crispy chicken sandwich, you need a four pound bird.

Chick-fil-A has always used smaller birds for its chicken sandwiches. Similarly, KFC says its fresh chicken on-the-bone comes from smaller chickens.

And that is the problem.

Chicken Markets

In the past, the goal was always a bigger breasted chicken.

The time it took to fatten a chicken decreased by two weeks from 1948 to 1951. By 1973, you needed only 8 1/2 weeks and breeders had figured out a “factory chicken.” As a result, during the 1950s, the U.S. became the pacesetter for mass producing chickens.

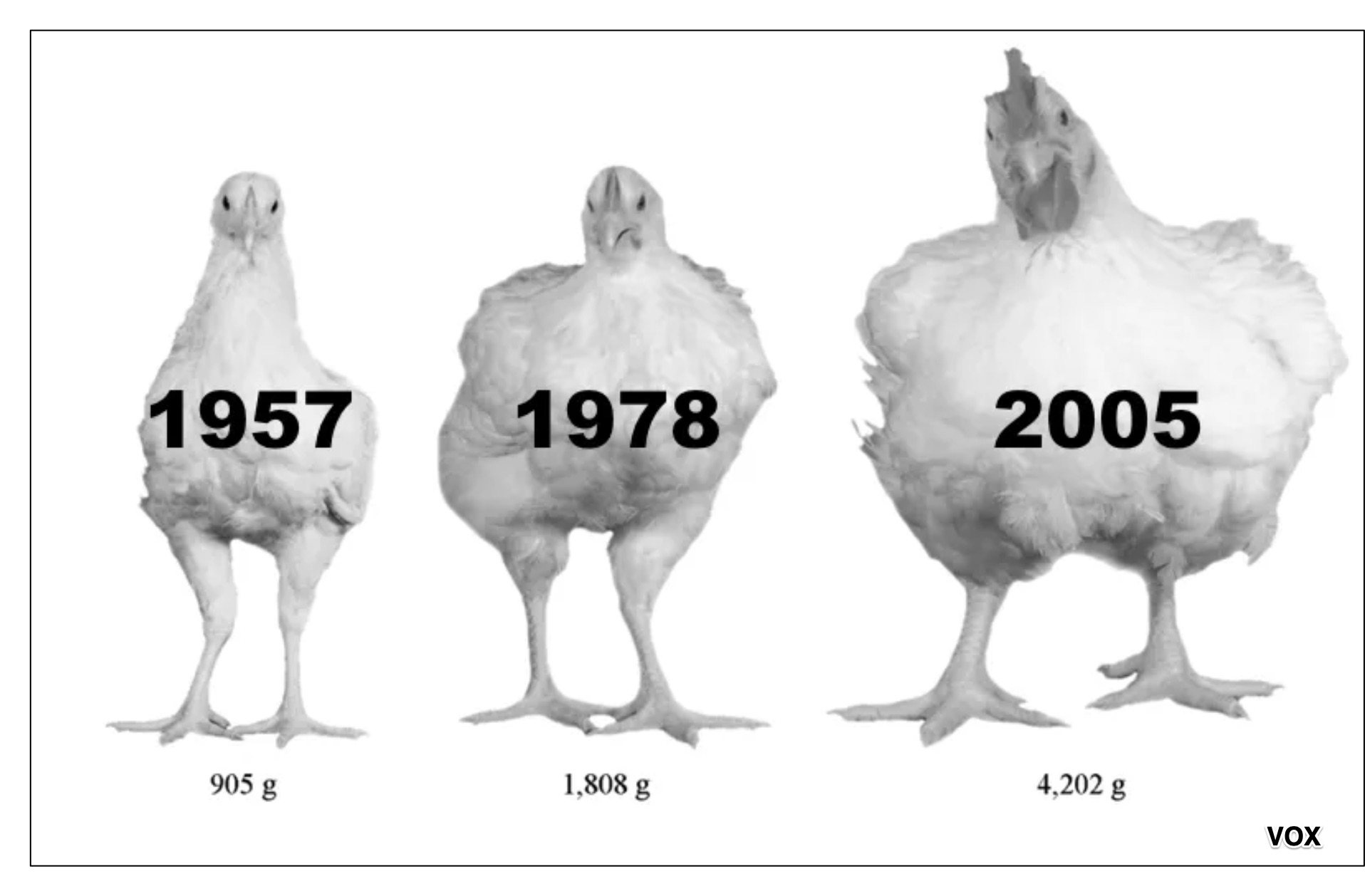

Continuing to progress, poultry farmers developed increasingly larger chickens. Below, each chicken is the same age. Still popular today, the 2005 chicken is a Ross 308 broiler. At 4202 grams, it weighs more than nine pounds:

Fed the same foods as its predecessors, the Ross 308 broiler is approximately four times as heavy. The reason is the “breast conversion rate.” Most simply explained, modern chickens turn feed into breast meat more efficiently.

And, they are more profitable. After all, the cost to produce a four or an eight pound chicken is similar. As a result, since 2005, the number of small chickens that are slaughtered decreased from 30 percent of the market to 15 percent this year.

Our Bottom Line: Chicken Economics

Chickens have always had economic significance.

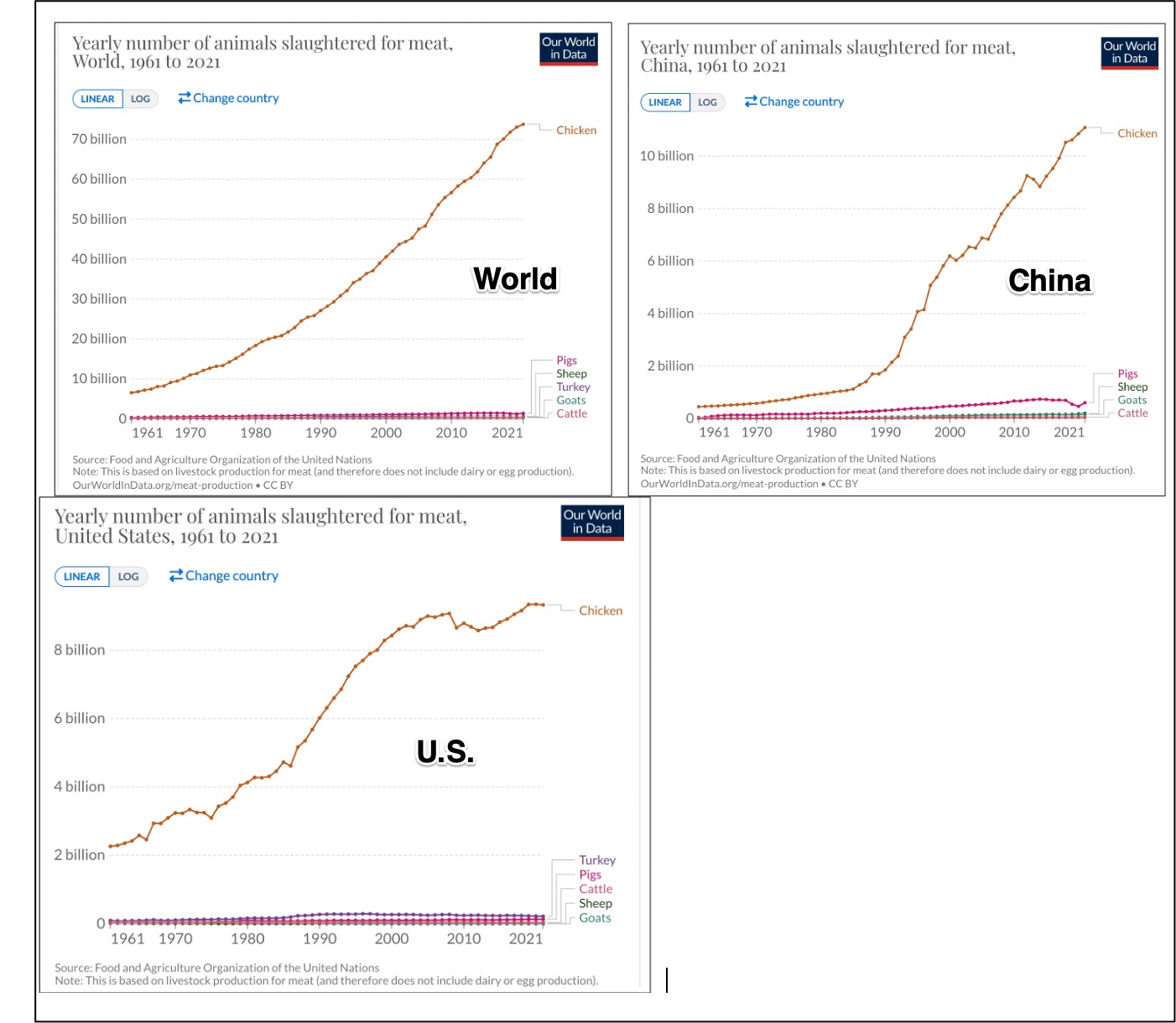

Fueled by what we could produce and growing wealth, we’ve increasingly became a world of chicken eaters:

Then, for the next chapter in this story, we can look at China during the 1990s. At that time, U.S. consumers were eating the breasts, the thighs, and the drumsticks but not the paws. At best, they were sold in dog food. But then, producers realized that Chinese paw consumption could be “bottomless.” A Perdue executive said he wished they could sell more but their supply was limited by the demand for the rest of the chicken. Still though, from nothing, paws had become a major source of profit.

The question now though is whether fast food chains can get the chickens they need for their customers. Like all innovation, it will depend on traditional market incentives.

My sources and more: As someone that likes little chickens, I was grabbed by this WSJ article. From there some chicken history made sense. Then, completing the picture, these articles and graphs from Our World in Data were ideal. (Please note that several of today’s sentences were in previous econlife posts. Also, our featured image is a Panera chicken sandwich.)

![econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo[1]](/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo1.png#100878)