Why Grade Inflation Is Tough To Tame

February 2, 2026

Where We Have To Define Candy

February 4, 2026Two years ago, we saw that Africa had a surge in port development.

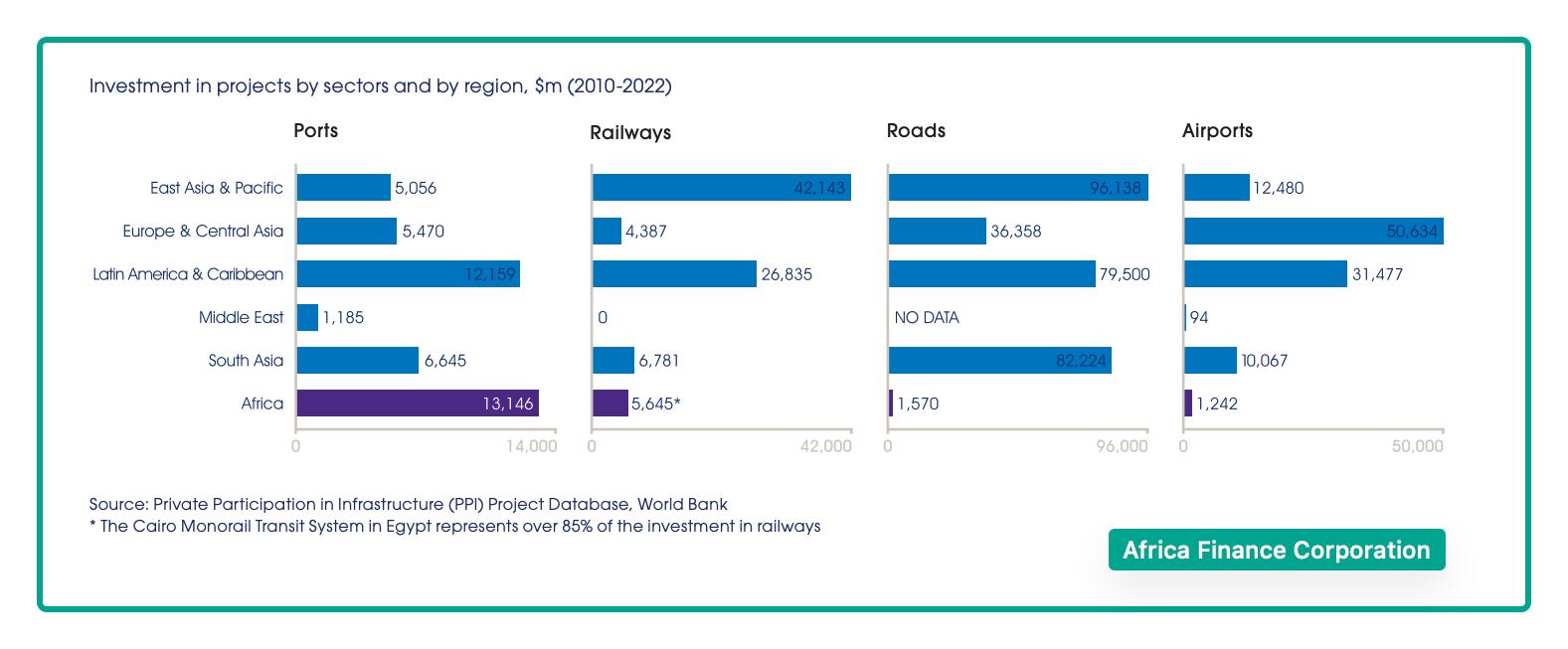

By contrast though, further infrastructure development has been inadequate. Those imports need the roads that facilitate distribution throughout the continent.

To see the need, we can do a global comparison. Africa represents 20% of the world’s land mass but only 1.5% of its paved roads:

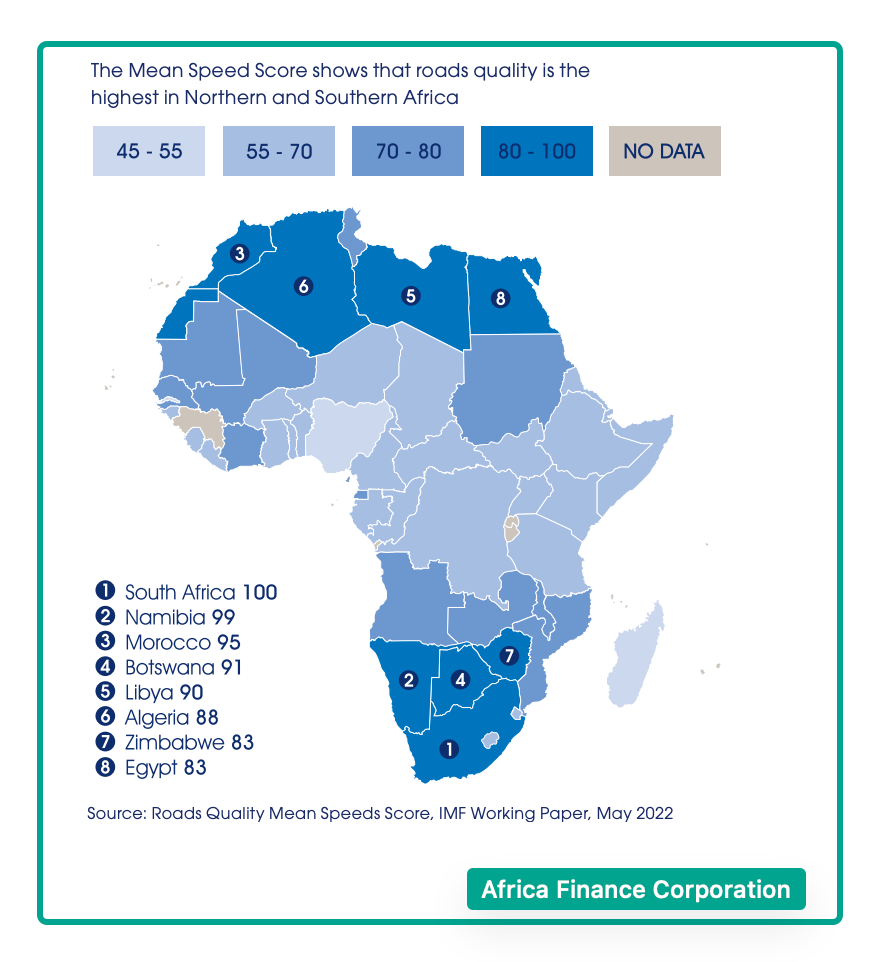

Also, looking at driving speed scores, we see a similar deficit. Most of the continent’s goods and people travel on roads that are “poorly maintained.” In addition, there is considerable disparity between North and sub-Saharan Africa. Concentrated in South Africa and Algeria, Africa’s paved road network is six times smaller than India’s:

The EMDE Transportation Infrastructure

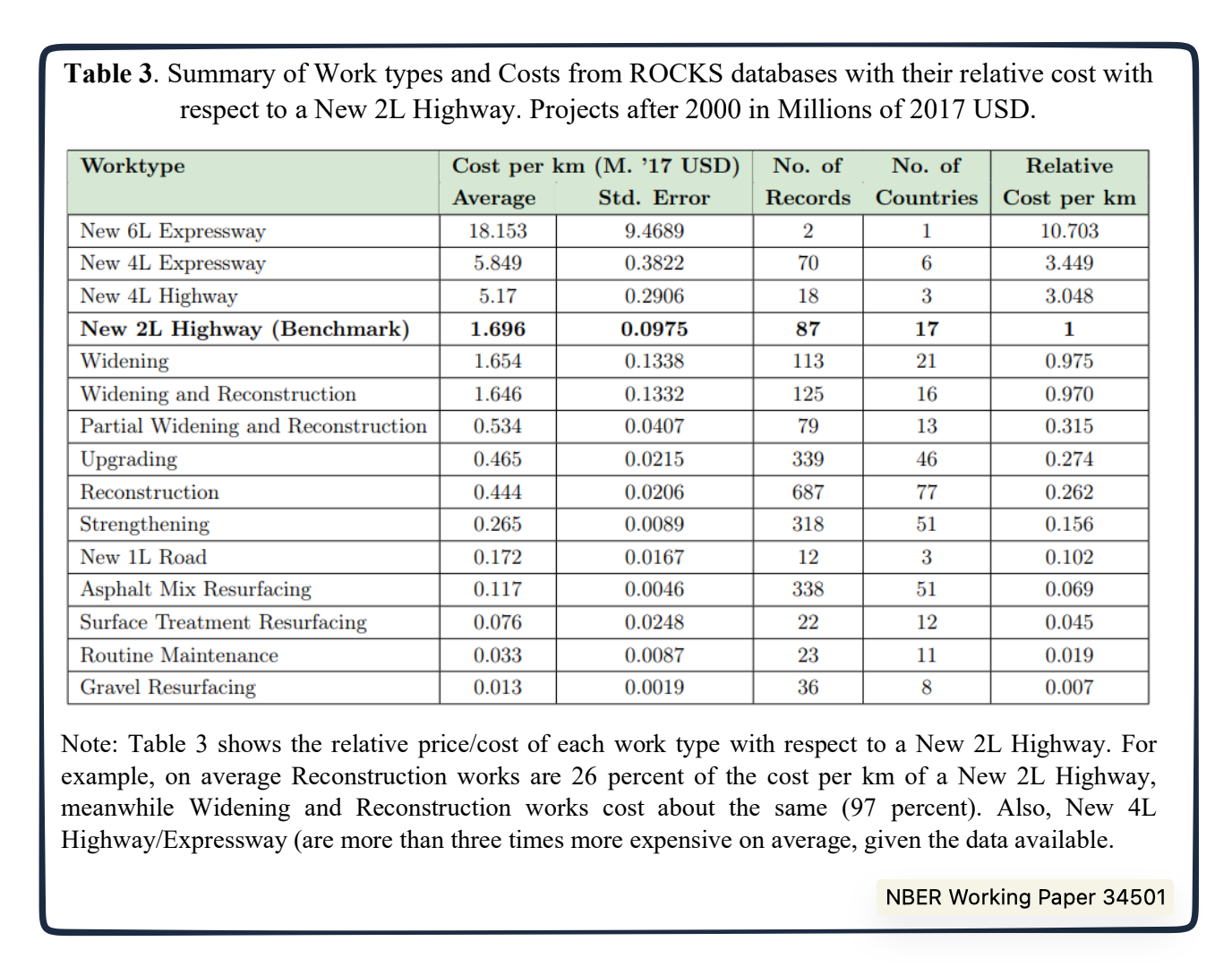

In a new NBER working paper, researchers demonstrate the lucrative potential of investing in EMDE’s roads (emerging markets developing economies). Looking at 55 EMDEs, they calculated returns that ranged from 230% in the Philippines to 30% in Cameroon. Their goal was to display that the social return from a new two lane road in a developing nation far exceeded (approximately by a multiple of 8) what investors could expect in a developed nation. One way that they figured out the return was to compare the initial investment to the GDP increase. (Returning us to one of my favorite economic ideas, they cited the GDP’s elasticity.)

They listed the requisites of an initial investment:

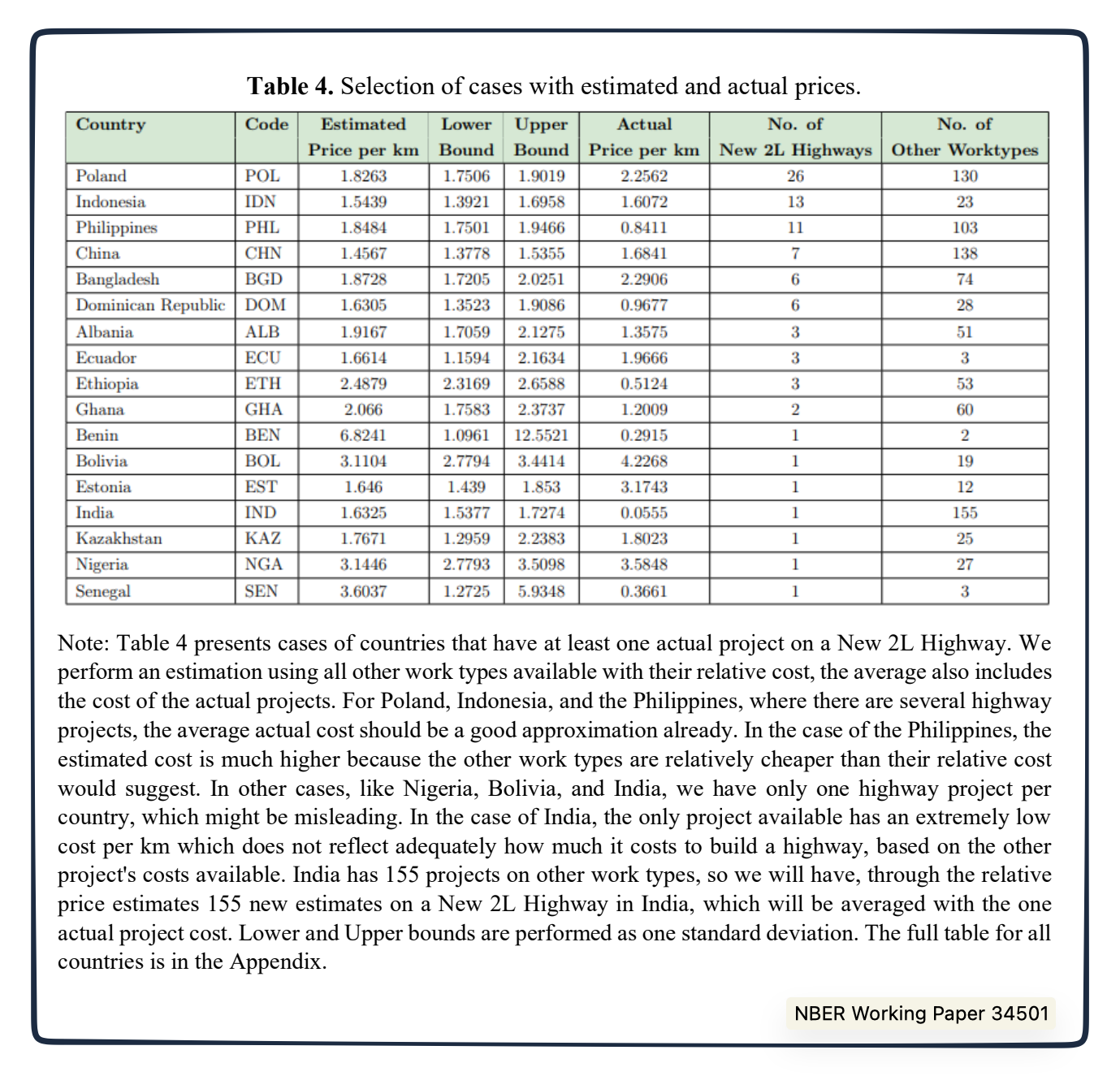

And some of the countries from which they accessed data:

Our Bottom Line: Transportation Infrastructure

The benefits of an African transportation infrastructure reminds me of the Erie Canal. Completed in 1825, the Erie Canal connected East and Midwest markets and served as a prototype for copycat waterways. It enabled regional specialization and the U.S. 19th century version of comparative advantage.

From Michigan to Connecticut and New York to Virginia, others sought to copy the Erie’s success. As a result, each part of the nation could specialize in what it did best. The Northeast could concentrate on manufacturing, the West could grow farm goods and raise livestock, the South could focus on cotton. What you did not provide locally, you could get from a distant place. Rocky New England farms no longer needed to grow tobacco. People in the South could stop making their own shoes. Easily, quickly, and cheaply, goods and people could move across the nation.

From there we built a transcontinental railroad system that connected the East with West by 1869. Easily, quickly, and cheaply, goods and people could move across the nation. As a result, by the end of the 19th century, the U.S. was on the road to becoming an economic dynamo.

Returning to Africa, we certainly see the economic potential that could evolve with a transportation infrastructure.

My sources and more: Thanks to my NBER digest email for alerting me to the infrastructure paper. Then, we also referred back to this econlife post.

Please note that several of today’s sentences were in a past econlife post. We should also note that while some of our data is at least four years old, there is no reason to believe today is different.

![econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo[1]](/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo1.png#100878)