Where to Find a Directive GDP

February 1, 2026

Where a Road Matters

February 3, 2026With “A” as 60% of all its grades, Harvard has proclaimed the need to rein in the bubble.

Their solution? Add A+ to the grade range. The reason? They seem to think that a grade beyond an A will provide a new way to recognize excellence since the “A” has lost its cachet.

Where are we going? To why grade inflation might not be solvable.

Grade Inflation

In 1950 a typical Harvard student’s grade was lower than a B+. By 2007 more than half of Harvard’s grades were in the A range. Then, last year, the proportion was 60.2%. Now, at 53.4% fall semester grade averages have slipped slightly.

You can see the trend has been up:

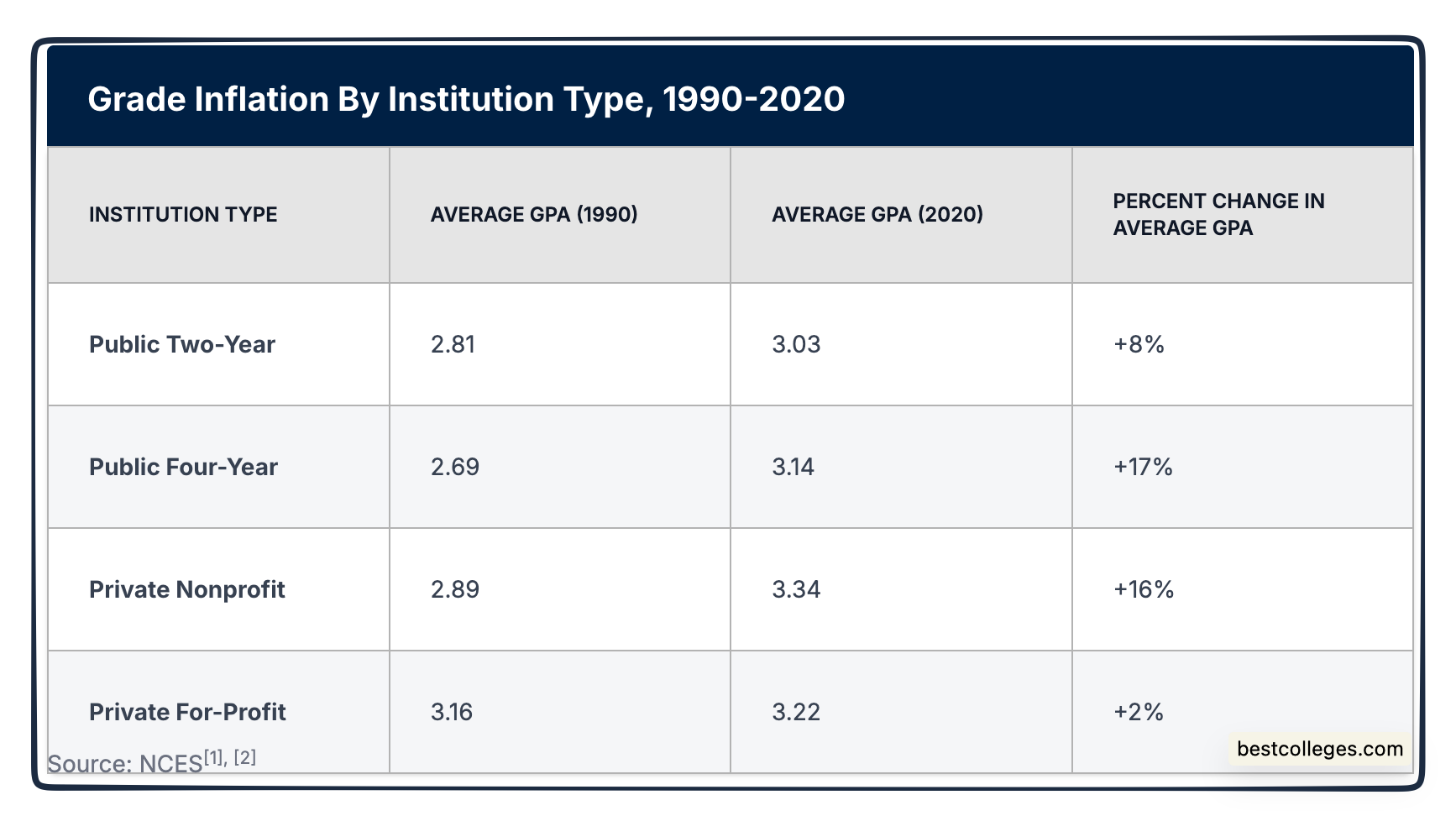

Elsewhere also, grade averages were rising:

Predictably, the median grade at Yale has been an A.

At 52.39%, Economics was low on a Yale list of the percent of A’s and A-‘s in classes with enrollment over 500. Meanwhile, The History of Science clocked in with a 92.37% rate (in other words, almost everyone):

Fighting Grade Inflation

Not only have attempts to bring grades down not worked but no one seems to have recently tried.

Cornell

As grade inflation accelerated during the 1990s, the Cornell Faculty Senate decided to experiment with transparency. Mandating the publication of median grades for every course, they wanted everyone to know whether an “A” was meaningful. The goal was to encourage enrollment in courses with tougher graders by more accurately recognizing performance.

It did not quite work out that way.

More students signed up for the courses offering easier A’s. Researchers did note that lower ability students rather than those who were more able tended to enroll in the easy grade courses. But the high ability students unknowingly created a problem for themselves. They wound up in classes with strict graders, more able students and more competition. Consequently, the high ability student’s transcript looked better in those easy grading classes with students of lesser ability.

Because transparency had created perverse incentives, in May 2009, the Cornell Faculty Senate abandoned their experiment.

Princeton

Twenty years ago, Princeton tried to conquer its grade inflation. Through a faculty resolution, instructors were asked to limit A’s to 35% of the grades they gave. Somewhat successful, the proportion of A’s dropped from a pre-2004 47% to 42% between 2010 and 2013. Opposition though came from younger faculty without tenure and from students. Meanwhile A’s at competing institutions continued ascending. Soon after new leadership arrived at Princeton, the policy disappeared.

Harvard

In addition to its A+ approach, a Harvard grades committee has suggested including median grades on student transcripts. They also noted that more attention to student mastery of a subject could further control the grades surge.

Our Bottom Line: Grade Inflation

Like prices, grades convey information and incentives. Grades tell students their strengths and weaknesses. On a transcript, grades send a message to other schools, to financial aid officers, and to job recruiters. As incentives, grades can boost or diminish effort.

However, when prices or grades inflate, they can lose their ability to convey information. Creating a bubble, the higher price or grade is filled with air rather than substance.

And with both, that bubble is really tough to pop.

My sources and more: The NY Times, here and here, inspired today’s post. From there this article had the details for other schools as did Marginal Revolution and the Yale Daily News.

Please note that several of today’s sentences were in a past econlife post.

![econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo[1]](/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo1.png#100878)