How a New Dam Gives Ethiopia Power

September 3, 2025

Why We Need Our Buoys

September 5, 2025In the U.S. we use MPG (miles per gallon). In Europe, it’s liters per 100 kilometers driven.

The metric makes a difference.

Perverse Incentives

Measuring Mileage or Gas

This quiz from Vox demonstrates how MPG can be misleading:

Which of the following saves more gas?

- “Swapping a car that gets 25 miles per gallon (MPG) for one that gets 50 MPG.”

- “Replacing a car that gets 10 MPG with one that gets 15 MPG.”

Answer: #2

Why?

- Gallons saved for a 100 mile trip? 2 gallons

- Gallons saved for a 100 mile trip? 3.33 gallons

Calculation:

- At 25 miles per gallon, we need 4 gallons for 100 miles while the 50 MPG car needs 2. Moving from 4 to 2, we save 2 gallons.

- 10 MPG means 10 gallons for 100 miles while 15 requires 6.67. So we save 3.33 gallons.

To figure out how to save gasoline, the Mileage Per Gallon route was rather indirect. However, liters per kilometers driven directly focuses on the gas we use. As a result, Vox suggests that a new metric like GPHM (Gallons of Gas Per Hundred Miles of Travel) would provide more of an incentive to burn less fossil fuel.

Measuring Household Work

Through research from the Levy Economics Institute at Bard College, the BLS (Bureau of Labor Statistics) concluded that the dollar value of unpaid household work is close to a whopping two-thirds of what we spend on goods and services. They estimated that for every $100 spent on commodities, the value of household production is another $65.

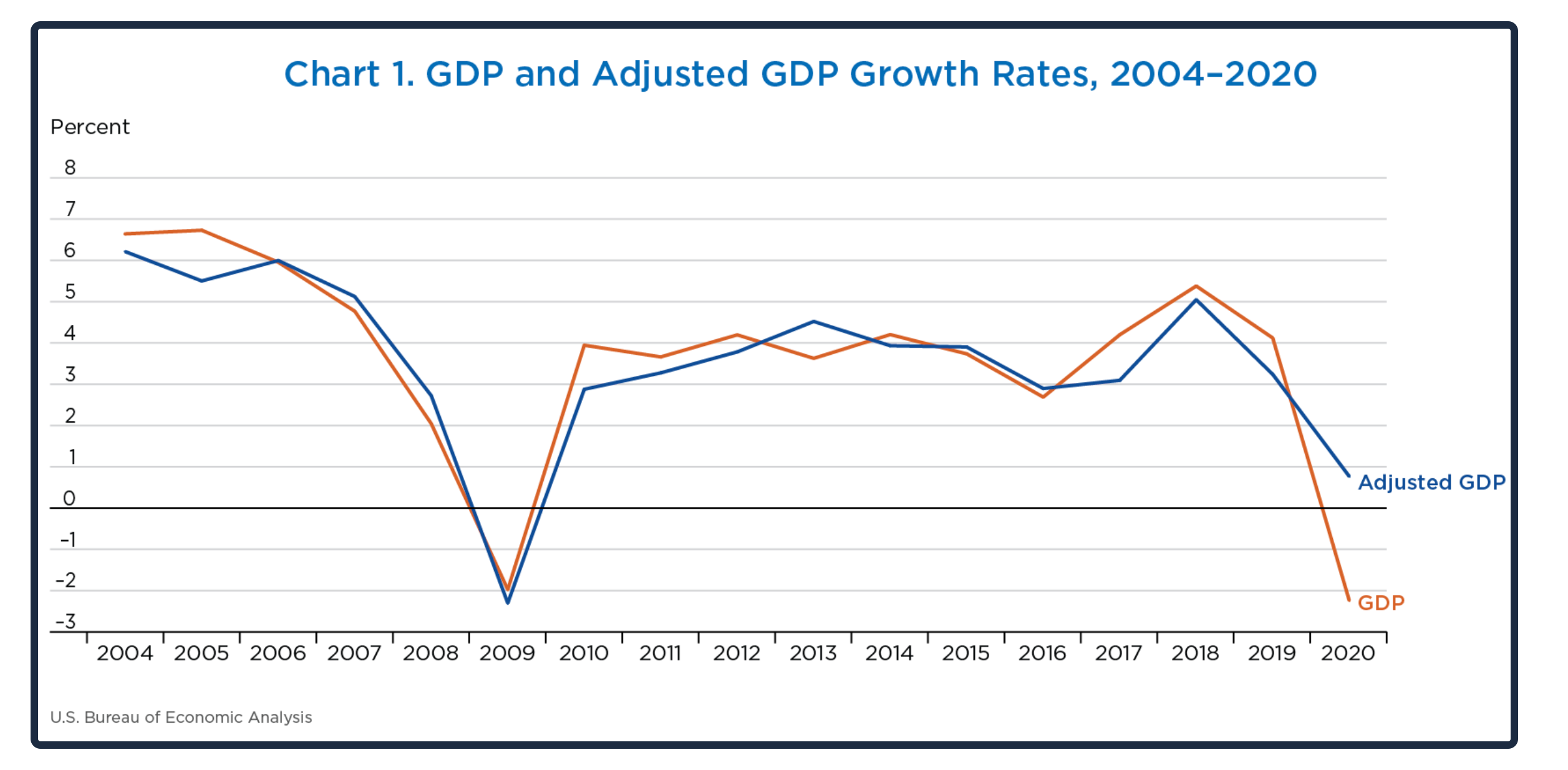

Shown as an adjusted GDP, this graph from the BEA displays the value of household production:

Like miles per gallon, the Gross Domestic Product shines a spotlight on production that diverts us from more attractive incentives. Because only a satellite account looks at household production rather than the official GDP, the ignored work becomes second class. The GDP also does not input the downside of economic growth. If it did, we would be more aware of the pollution and illnesses we create as well as the upside of economic growth and innovation.

Our Bottom Line: We Treasure What We Measure

When Nobel Laureate Simon Kuznets first created the GDP concept during the 1930s, he decided that only market based paid work could be included. Since there was no market metric for work done at home, it was not counted. Remembering that we “treasure what we measure,” we wound up undervaluing childcare, elder care, grocery shopping–all you do to run a household.

Consequently, whether it’s driving or doing the dishes, what we do and don’t count can create perverse incentives.

My sources and more: Thanks to Todd for inspiring today’s post. Pondering gas mileage, we started with this Vox article. From there, we looked at other metrics that redirect our attention. Our data on the home came from Bloomberg and this paper.

Please note that several of today’s sentences were in a past econlife post.

![econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo[1]](/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo1.png#100878)

2 Comments

Rather than perverse incentive, I would call mileage confusion the inability to assimilate the broader technique of inversion that you used in sixth grade rate problems (Joe can shovel the driveway in two hours; Jim can in three hours; together they can do it in 1.2 hours).

Then, when you grow up, you misunderstand mileage economics, as well as probabilities (i.e., if there is a 70% probability of rain today, and a 70% probability of rain tonight, then the probability of rain, inclusive, is 91%, not 140%)

Agreed.

Can we then take the next step and say we wind up with a perverse incentive?