How to Find a Bubble

January 12, 2026President Trump said he is considering a one-year 10% cap on credit card interest rates. Requiring Congressional legislation, he probably could not do it alone. Last February, two senators did propose a 10% cap, but the bill stalled.

Classic economics, a cap is a ceiling with a slew of tradeoffs.

We should take a look.

Credit Card Interest Rate Caps

History

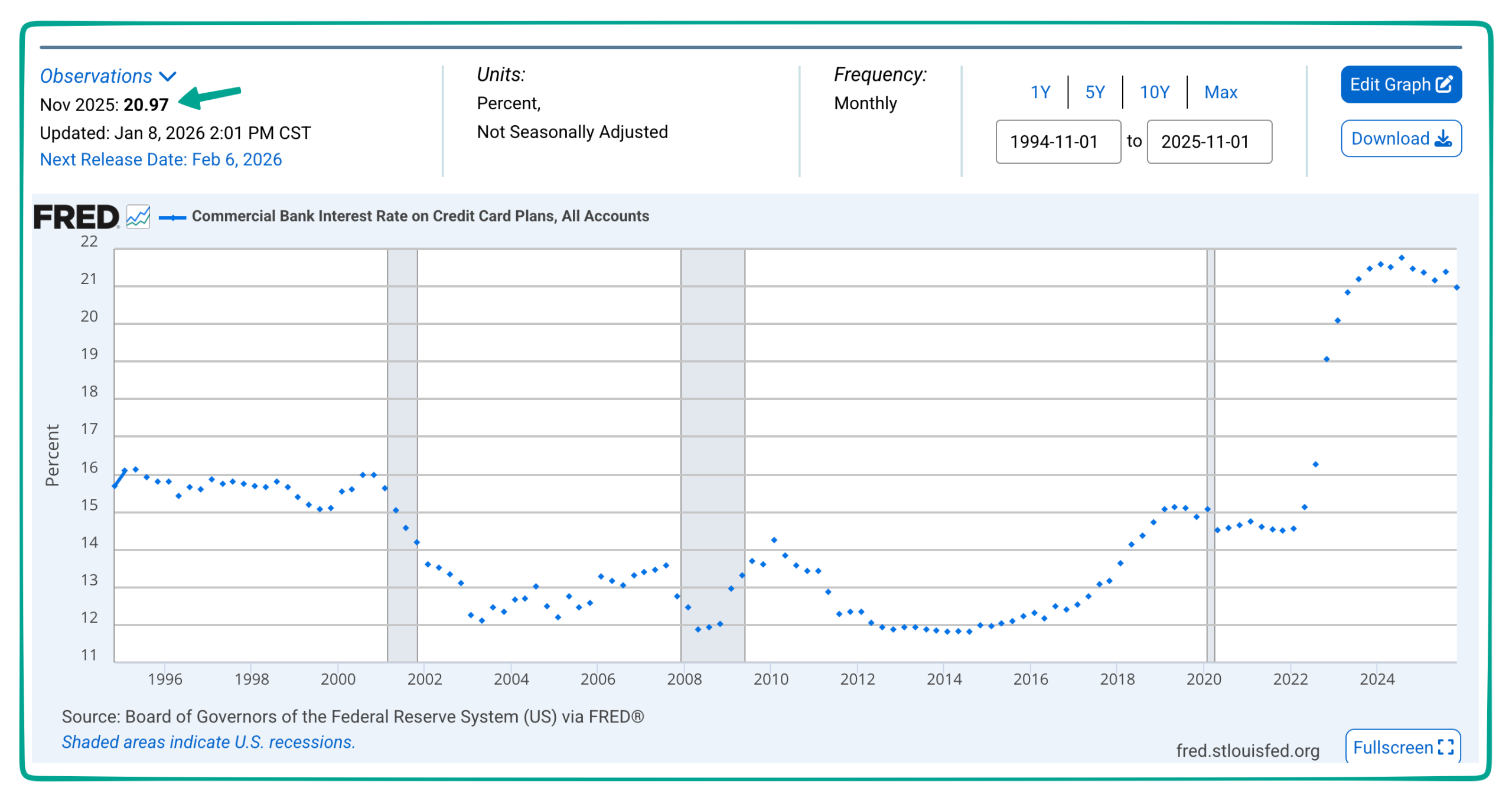

According to the Federal Reserve, on all accounts at commercial banks, rates soared beyond 20% as of November, 2025:

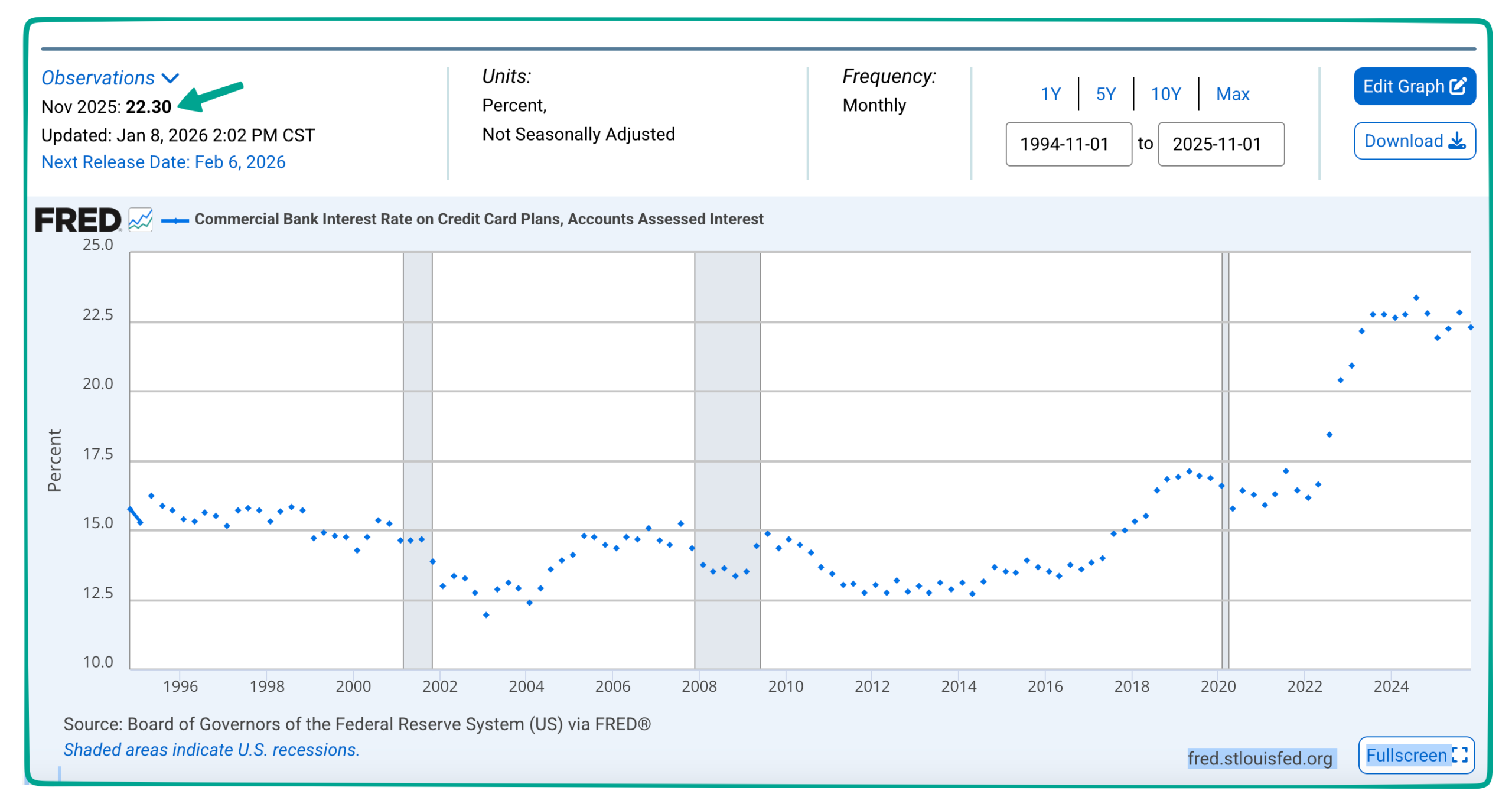

Meanwhile, the rate was even higher for accounts with assessed interest:

Two reasons for the elevated charges are the volume of delinquencies and a higher rate climate.

1930s Interest Rate Caps

For their September 2025 paper, researchers looked at the impact of an interest rate cap on loans during the Great Depression. Ideal for data, the study could compare the impact of lowering an interest rate ceiling in 1929 and then raising it again in 1931. When the cap descended from 3% to 1.5% per month, small loan activity shrunk. Responding, brokers left the business and market concentration increased. Then, when the cap went up to 2.5% per month, loan activity also accelerated.

The result was a classic tradeoff. Yes, a cap protects borrowers from predatory high rates that can extend and elevate loans. However, the policy also diminishes loan availability for vulnerable populations when, unable to price for risk, lenders shut out high risk borrowers.

2026 Interest Rate Caps

Now, almost a century later, the debate remains the same. When you take borrowing costs below market equilibrium, you support households with outstanding balances. At the same time, though, by constraining banks’ profits from credit card loans, you encourage them to become more restrictive through new fees, standards, and card features.

The tradeoff is between protection and accessibility. By jeopardizing the subprime slice of loan markets, policy makers simultaneously offer protection and fewer options for home and car buyers.

Our Bottom Line: Ceilings

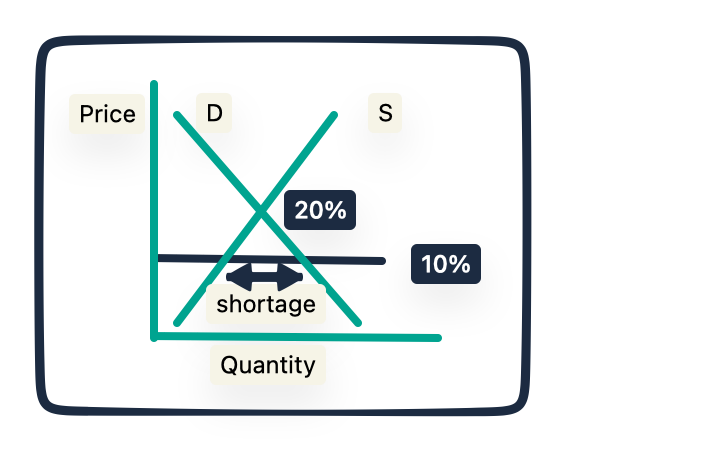

The price of a loan is the interest rate. Based on our FRED data, we can select 20% as an equilibrium rate and see the probable impact of a 10% cap:

Touching the supply curve to the left of the quantity demanded, like all ceilings, we create a shortage. While the most typical example is rent control, here we have credit card interest rate caps.

My sources and more: Research for a credit card interest rate cap took me to this Reuters Explainer, an NPR article, and delightedly to this NBER paper. Then, with its credit card rates, the St. Louis Fed’s FRED, here and here, came in handy. And most crucially, thanks to Todd for suggesting today’s post.

![econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo[1]](/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo1.png#100878)