When Accurate Statistics Are a Crime

August 18, 2025

Why Denmark Will Have a Burp Tax

August 20, 2025CNN tells us that the U.S. consumes 516 million cups of coffee each day. Averaging three daily cups, 82 percent of all coffee drinkers enjoy their coffee at home while the remaining 38 percent buy it “on the go.” Almost all of this coffee–99 percent–comes from the “coffee belt.”

Coffee Tariffs

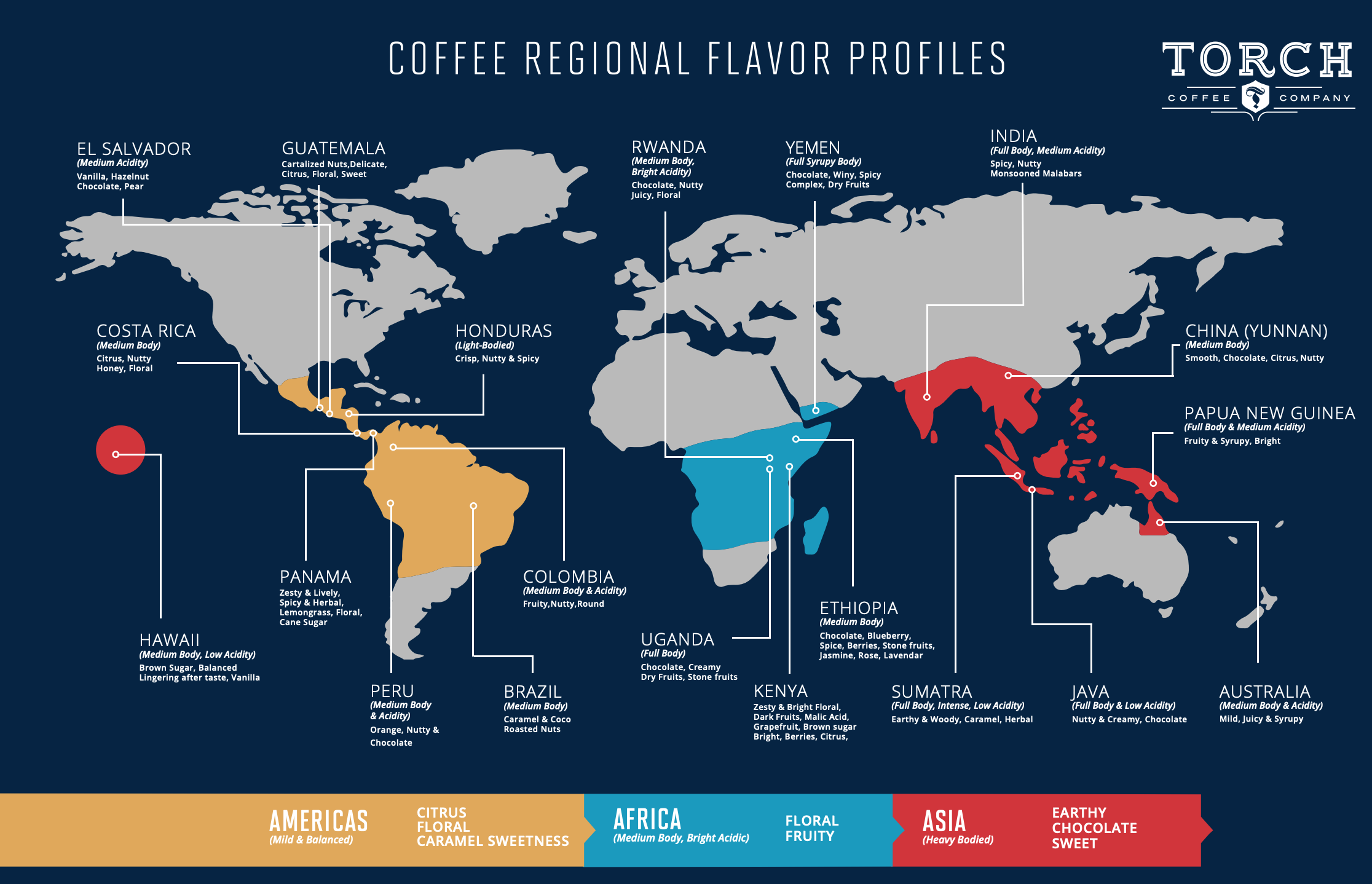

Sort of like bananas, to be happy, coffee needs heat and humidity. Looking at a map, you can see what has been called the “coffee belt” stretching around the middle of the world:

Far from the belt, the U.S. can recreate its environment in patches of Hawaii and Puerto Rico. Southern California also has a bit of coffee growing potential but little potential for scale because of pricey labor. As a result, as the world’s largest coffee-consuming nation, the U.S. has to import most of it.

From here, it gets more complicated.

The life of our coffee begins in the tropics. But then it has travel to where it is processed, roasted, packaged, brewed, served.

And that is where tariffs will create countless different incentives.

- The Nespresso pods that are produced in Switzerland will be hit with 40 (ish) percent tariffs.

- Meanwhile, the Colombian beans (behind Brazil, second largest coffee exporter to the U.S.) that come here directly could have a 10 percent rate.

- As for Brazilian beans (30 percent of the coffee we consume) a 50 percent tariff especially hits the large buyers like Starbucks..

- And, we could separately list the tariff rates slapped on India, Indonesia (my favorite for its Sumatran beans), and Vietnam.

Even before the tariff threat, coffee prices had increased. During February arabica’s price, at $4.41 a pound, touched an all time high. Now, though, prices are below their highs.

Our Bottom Line: Comparative Advantage

Explaining why we should trade, nineteenth century economist David Ricardo could have been talking about the coffee belt. Ricardo said that each country should produce whatever items require the smallest sacrifice. Then, by trading, together, we all become more productive. Indeed, by devoting land, labor, and capital to growing coffee or stitching t-shirts, we would be sacrificing the grains that grow happily in the Midwest or the factories that would make computer chips (or potato chips).

Called comparative advantage, coffee producing countries sacrifice the least to grow and export their commodity to us. Faced with 19th century tariffs on grain imports in Great Britain (called the corn laws), Ricardo said no because of the higher prices consumers paid and the distorted incentives. Similarly today, he would have shouted, “No.” And also smiled at all of the other nations enjoying the benefits of comparative advantage–just not us.

My sources and more: Thanks to The Hill for inspiring today’s post. From there, The Washington Post and CNN had more tariff detail, and Yahoo Finance told us about the Starbucks hit. Also, investigating coffee, I was delighted to have discovered our map at this website.

![econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo[1]](/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo1.png#100878)