Our Weekly Economic News Roundup: From Strawberries to Soybeans

October 11, 2025

The Invisible Benefits of Immigration

October 13, 2025Imagine 82,880 T-shirts in this box:

To see the impact of tariffs, we just need to count the boxes.

The Box

But first some history.

Our story begins In 1956 when Malcom McLean modified an oil tanker docked in Newark, N.J. His goal was to transfer container boxes from trucks into slots on the vessel. Then, when they arrived in Houston, only the containers had to be unloaded, and shipped to stores and warehouses by rail or truck.

The cargo container was revolutionary.

Before the container, t-shirts, flour, and bananas were packed in barrels or bags or crates. Transported by truckers to waterfront docks, it could have taken weeks and gargantuan worker hours to load them onto ships.

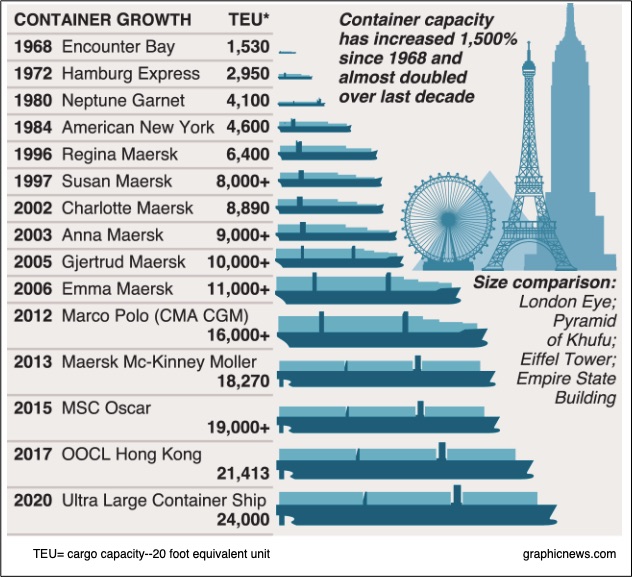

Leaping to 2015, we have just one container ship carrying 39,000 cars, 117 million pairs of sneakers, or 900 million cans of dog food. Whereas moving your cargo 1,000 feet from the street to a ship could have taken as long as an entire ocean trip, instead the time plummeted:

And so too did cost:

As a result, moving from raw materials to assembly, one iPhone could have started its journey in Brazil, stopped at Vietnam and South Korea, and wound up with a slew of other components that were all shipped to a Chinese assembly plant.

Typical for countless commodities, you can see that it all adds up to a lot of boxes:

Tariff Impact

Now though, during September, we have an 8.4%, yr/yr drop in container box shipments carrying U.S. imports while from China, the plunge is 23%. Down from last year, still U.S. ports received 2.31 million 20-foot equivalent units (TEUs as shown in our above box image). The numbers have peaked because, according to the NRF (National Retail Federation), retailers, sidestepping tariffs, frontloaded imports.

More precisely, imports from China were down a whopping 762,772 TEUs. Those boxes would have been carrying toys and footwear, apparel and aluminum, electric machinery and sporting goods.

Our Bottom Line: Comparative Advantage

Fewer TEUs mean a hit for comparative advantage. First explained by David Ricardo during the early 19th century, comparative advantage is the reason economists love trade. As they explain, each country just needs to produce the items for which they have the lower opportunity cost (and sacrifice the least). Stated most simply, then we all trade and the world is more productive.

Now, because of tariffs, we enjoy less of the comparative advantage that brings the shoes and shirts that others should be making.

My sources and more: Thanks to Reuters for the TEU update. As always, when we return to the box (my favorite), I recommend the book that tells the whole story.

Please note that several of today’s sentences were in a previous econlife post.

![econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo[1]](/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/econlifelogotrademarkedwebsitelogo1.png#100878)